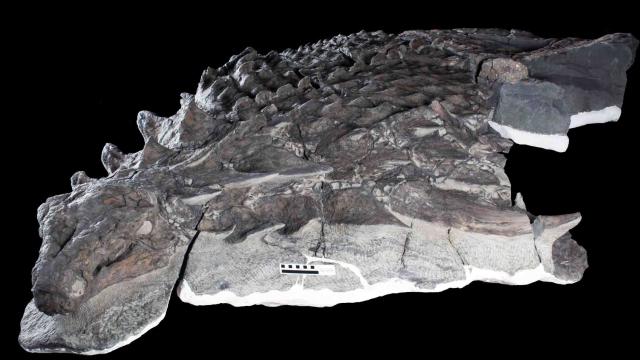

Fossils don’t get much better than this. (Courtesy of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, Drumheller, Canada)

On a fateful day in the Early Cretaceous, a large, four-legged armoured dinosaur dropped dead on a beach in what is now modern day Alberta. The remains of this 5.49m-long beast drifted out to sea and eventually sank, where it became buried in a thick layer of mud. Over time, the dinosaur became petrified, its soft tissues replaced by hard minerals. And then, quite by chance — some 110 million years later — a Canadian mining operator stumbled upon what is now considered to be one of the finest fossils ever discovered.

The world caught its first glimpse of this magnificent “mummified” specimen back in May, when National Geographic released a set of remarkable images showing not a jig-sawed collection of re-assembled bones, but an intact animal that still appeared to be wearing its original skin. The combination of extensive skin and scale preservation (including organic layers), intact horn sheaths, and the retention of its original shape offered a rare snapshot of a dinosaur as it appeared 110 million years ago. As Royal Tyrrell Museum paleontologist Caleb Brown told Gizmodo, “This is one of the best preserved dinosaurs in the world.”

Brown, along with a team of international researchers, has now completed the first extensive analysis of this extraordinary three-dimensional fossil. As the new study points out, Borealopelta markmitchelli, as it’s now known, featured a common form of camouflage called countershading. This suggests the nodosaur, despite being heavily armoured and weighing 1,270kg, still needed to hide from predators. The researchers inferred the animal’s pigmentation pattern by performing a chemical analysis of the organic residues still found in its scales. The results of this analysis were published today in Current Biology.

Artist’s recreation courtesy of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, Drumheller, Canada

Countershading is an extremely common form of animal camouflage, seen in animals like deer, rabbits, penguins, and sharks. It’s where the back of an animal is more darkly pigmented than its belly, which is paler. The principle behind it is a process known as self-shadow concealment.

“Imagine the 3D form of an animal in sunlight from above, the back of the animal will be well lit, while the belly will be in shadow,” explained Brown to Gizmodo. “With countershading, the pigment of the skin is opposite to this pattern of light, such that the two will cancel out, and the 3D form of the animal will be less obvious.”

This form of camo works both for predators that sneak up on prey, and prey that need to hide from predators. But when prey species get large enough, they often don’t have to worry about predators. Today, elephants and rhinos are good examples of this; they’re generally not countershaded, exhibiting a more solid colour across their large bodies. Prior to this latest study, paleontologists figured that large dinosaurs, like large extant mammals, wouldn’t need this form of camo, but Borealopelta suggests that isn’t always the case.

“The presence of countershading on Borealopelta markmitchelli therefore suggests that despite it weighing 1,300 kg [1,270kg] and being covered in body-armour like osteoderms [i.e. bony deposits forming scales, plates or other structures] — some up to half a meter long — it would have still experienced predation stress from large [predators].” said Brown.

A researcher prepping the fossil for study. (Image: Courtesy of the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology, Drumheller, Canada)

Aside from the countershading, Brown admits there isn’t much other evidence to prove that Borealopelta and other armoured dinosaurs were preyed upon. Bite marks on bones are rare and ambiguous, and stomach contents are typically restricted to small animals. That said, many armoured dinosaurs are preserved upside down, which might imply they were flipped over by predators to get at the softer underbelly. Brown disagrees, saying these carcasses were likely turned over by natural processes.

“The lack of evidence for predation on large dinosaurs, however, should not be seen as evidence that they were free of predation, just that this kind of evidence is hard to get,” he said. As for which dinosaurs made Borealopelta their lunch, Brown suspects two-legged theropods like Acrocanthosaurus, or a similar large Carcharodontosauroid — a bipedal beast even larger than Tyrannosaurus and Spinosaurus.

Aside from using its countershading to evade superpredators, Borealopelta spent its days eating large amounts of low lying vegetation, using its massive stomach as a fermentation chamber to extract more nutrients out of the food. It lived on the coastal plain of a large inland sea that used to cut North America in half, at a time when this area was warm, lush, and flat.

“Beyond this, it is difficult to provide more details about the environment, because the animal was not preserved in the environment it lived in,” Brown told Gizmodo. “Compared to other assemblages further south (but from a similar time), we can suggest the Borealopelta shared its environment with a variety of other animals like turtles and crocodilians, many other plant-eating dinosaurs, and carnivorous dinosaurs including small ‘raptors’, and large carnivorous theropods.”

As for the physical attributes of the species, it was similar in size and build to other nodosaurs, about 18 feet (5.5 meters) long. Ironically, the incredible preservation of the specimen is making it difficult for the paleontologists to learn more about it.

“The greatest limitation to this study was that the specimen was, in some ways, too well-preserved,” said Brown. “What I mean by this is that much of the internal skeleton is obscured by the large amounts of skin that is preserved. The patterns of relationships between armoured dinosaurs is largely based on the features observed on the skeleton. We attempted to CT scan the blocks to reveal the internal skeleton, but the rock proved too dense and radio-opaque. As a result, although this is an amazingly preserved and complete specimen, we would have had a better idea of how it compares to other armoured dinosaurs if it had less skin preserved. Hopefully new scanning technology in the future will allow us to see inside the animal.”

Which would be amazing. Should scientists figure out a way to peer inside this stone-solid specimen, paleontologists could study its stomach contents to deduce its last meal, and work out its skeletal and armour structure in greater detail. For now, we’ll just have to marvel at the exterior of this remarkably well-preserved beast.

As a final note, the specimen is currently on public display at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Drumheller, Alberta. Road trip!