Say hello to Macrobiotus shonaicus, a completely new species of tardigrade – those incredibly resilient microscopic wee beasties that likely have what it takes to survive the apocalypse.

Tardigrades, sometimes referred to as moss piglets or water bears, are eight-legged microscopic animals that like to live in moss, lichen, decaying leaves, and soil. These metazoans, first discovered in 1773, are incredibly resilient, capable of withstanding total dehydration, extreme temperatures and pressures, intense radiation, and the vacuum of space. They typically live a few months, but one lived more than 30 years after being frozen. Tardigrades can be found all over the world, and there over 1,000 described species so far — but scientists think there could be many more.

There are 167 known species in Japan alone. The addition of M. shonaicus now increases this number to 168. The new tardigrade was found in a clump of moss that was sticking out of a concrete parking lot in Tsuruoka-City, Japan. The name shonaicus refers to the Shōnai region in which it was found. M. shonaicus belongs to the hufelandi group of tardigrades, whose eggs have similar characteristics.

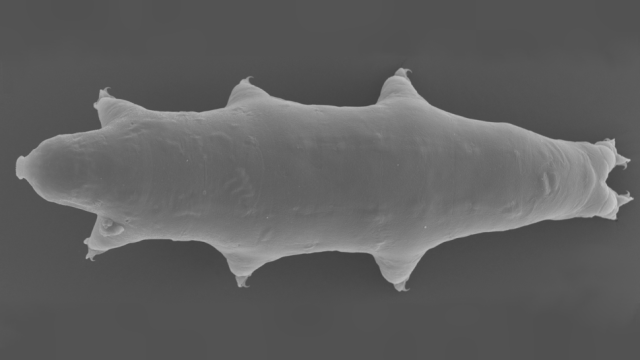

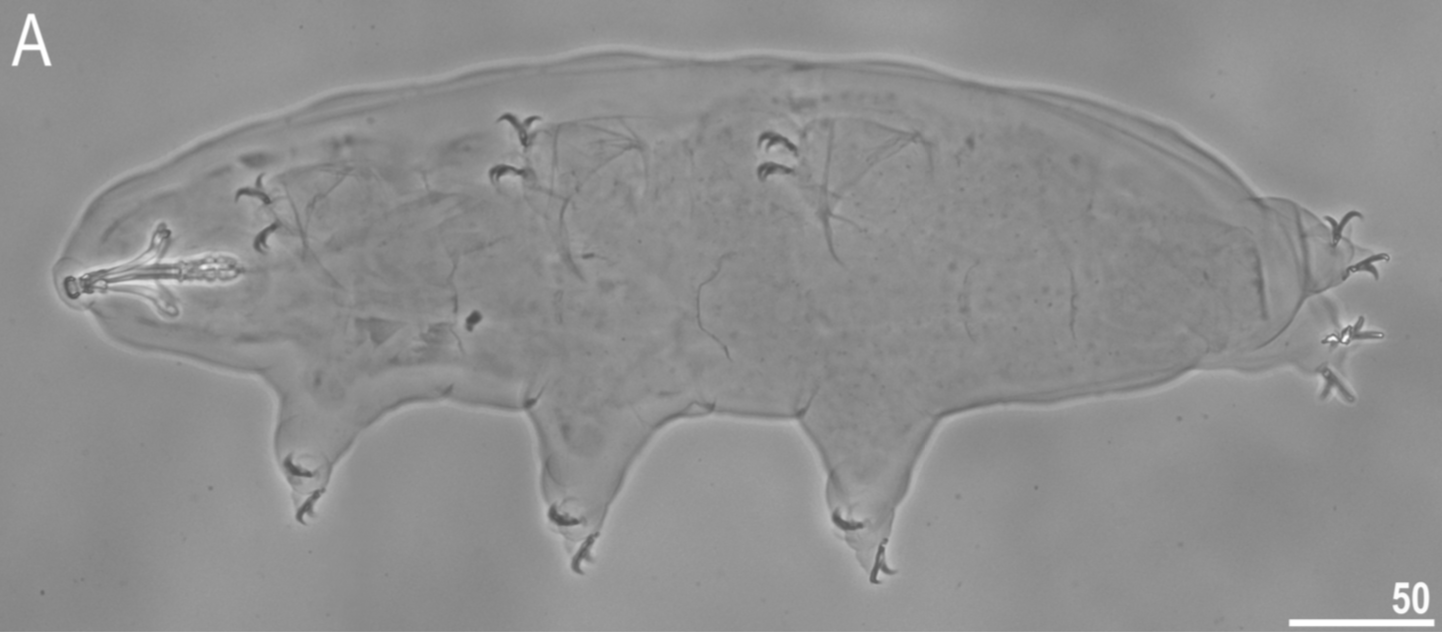

A view of the new tardigrade as seen through a phase contrast microscope.Image: D. Stec et al., 2018

The research team, led by Daniel Stec from Jagiellonian University in Poland, found 10 individuals in the moss sample taken from the parking lot. These specimens were bred in the lab to produce more tardigrades for the analysis. The researchers studied their physical characteristics using phase contrast microscopes (where a transparent object is conveyed through changes in brightness) and scanning electron microscopes.

They also looked at their DNA, and they pinpointed four molecular genetic markers that distinguish these from any other known species of tardigrade. The DNA analysis also allowed the researchers to determine where the new species fits in the tardigrade evolutionary family tree. This research was published today in the open access journal PLoS One.

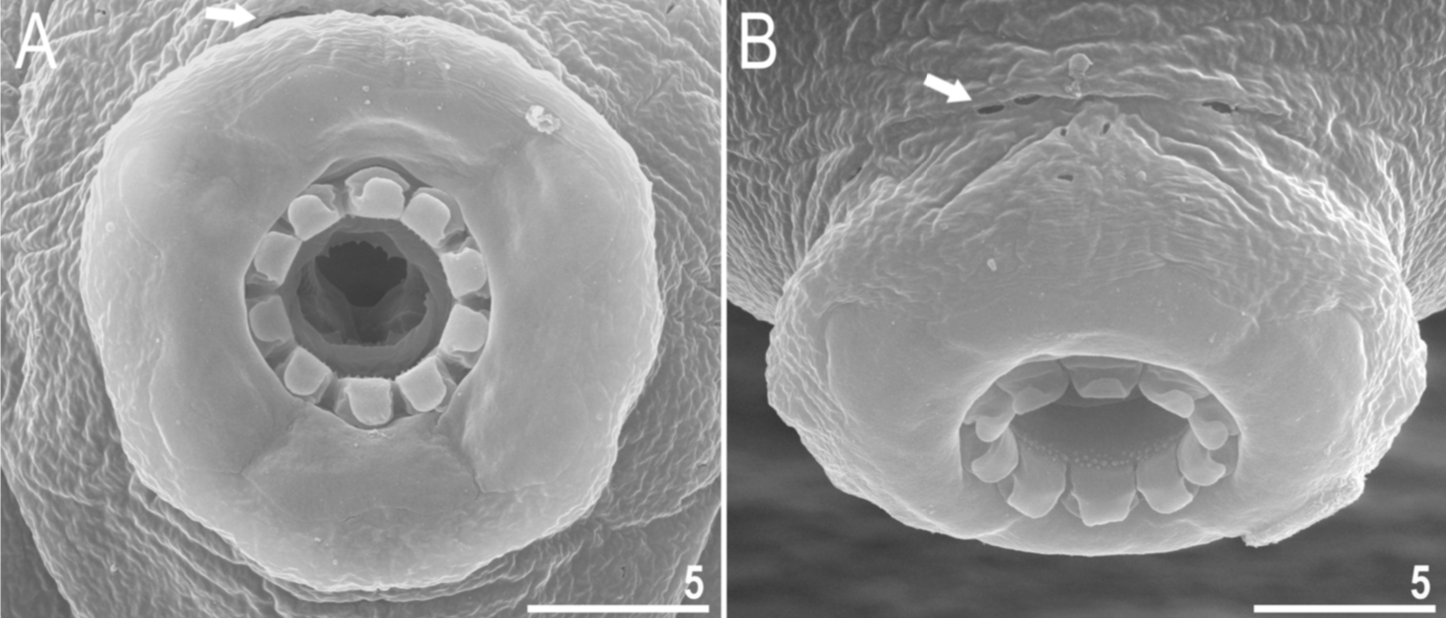

My, what strange teeth you have. The oral cavity of the new tardigrade. Image: D. Stec et al., 2018

When comparing the new tardigrade to similar species such as M. anemone, M. naskreckii, and M. patagonicus, the researchers noted differences in their visual organs, mouth, spotting, leg shape, and other features. But there were two big differences that set the new species apart: its legs and eggs.

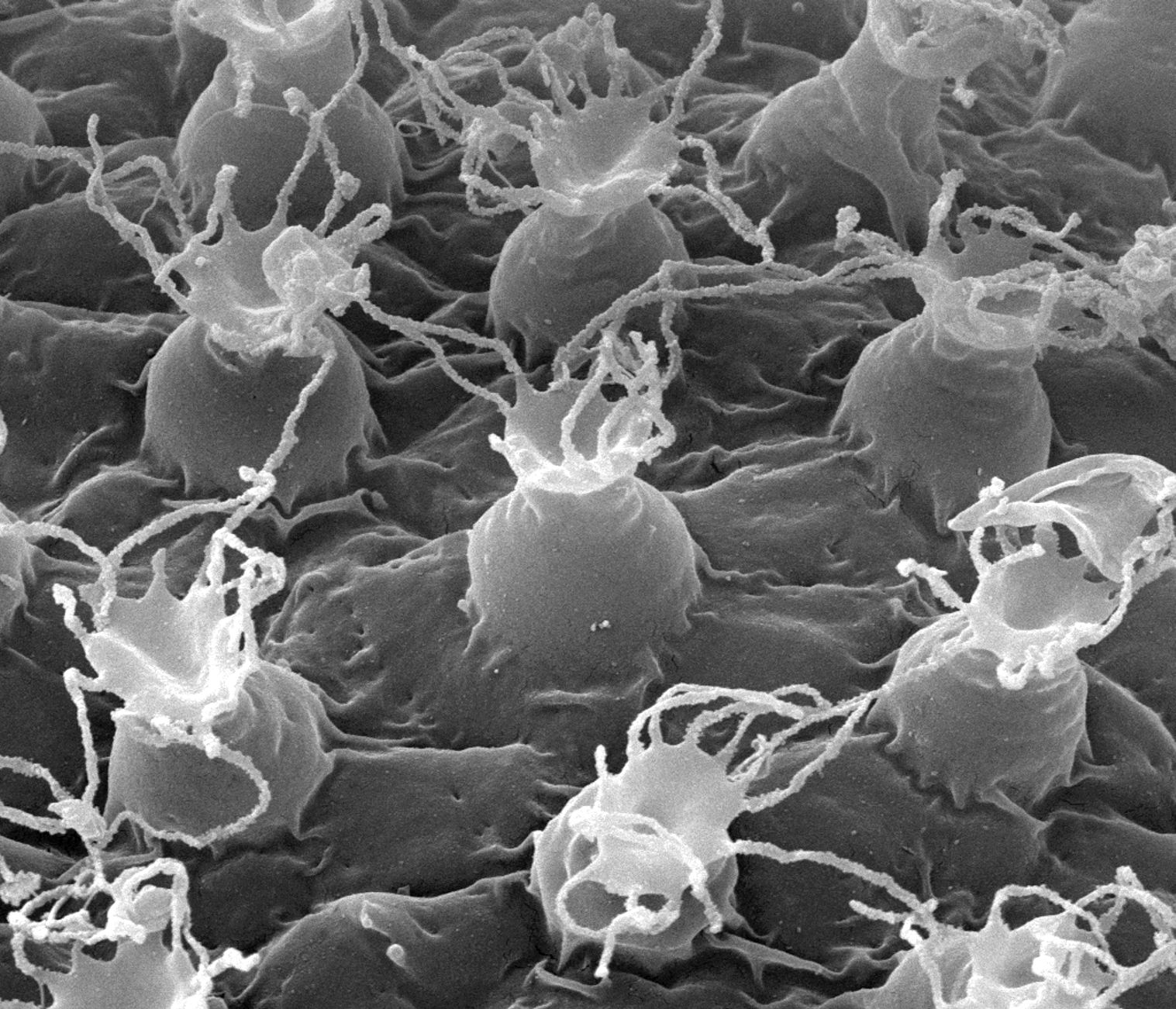

M. shonaicus has a fold, or bulge, on the internal surfaces of its legs, and its eggs have a solid surface, thus qualifying it as a member of the hufelandi sub-group of tardigrades. But the eggs also have flexible filaments attached to their tops, which is similar to the eggs produced by two recently discovered tardigrade species, Macrobiotus paulinae from Africa and Macrobiotus polypiformis from South America. So the new species contains a mishmash of characteristics from other species, and it’s likely descended from an ancient strand.

The eggs of the new tardigrade are capped with flexible filaments. Image: D. Stec et al., 2018

“This is the first original description of the hufelandi group species from Japan, and now, the number of tardigrade species known from this country has increased to 168,” write the authors in the new study.

Finding new species of tardigrades is good because we stand to learn a lot from these critters. Their ability to withstand freezing, for example, can help scientists develop “dry vaccines,” where water is replaced with trechalose — a non-reducing sugar produced by tardigardes to protect their tissues and DNA when frozen. Also, their dehydration tolerance could teach us new ways to preserve various biological materials, such as cells, crops, and meats.

So thank you, water bears, for your extraordinary genetics.

[PLoS One]