When people immigrate to the United States, their microbiomes quickly transition to a US-associated microbiome, according to research published today in the journal Cell. Changes to their internal population of bacteria start to occur within nine months, and the longer someone lives in the US, the closer their microbiome is to that of a US-born person.

“When you move to a new country, you pick up a new microbiome from that country,” study author Dan Knights, professor in the Biotechnology Institute at the University of Minnesota, told Gizmodo.

Our microbiome seems to have important, if poorly understood, impacts on our health, and the new study could help to explain things like the spike in prevalence of obesity — which is linked to gut bacteria — in immigrant groups after they arrive in the US, according to Knights.

Minnesota is home to Hmong and Karen refugees, minority ethnic groups from Southeast Asia. The research team collected stool samples from over 500 Hmong and Karen individuals, including people living in Thailand, who represented the pre-immigration cohort, people who recently moved to the US, and second-generation immigrants. They also took samples from 36 US-born people with European-American ancestry to serve as a control.

The team used a community-based participatory research model for the study. “That entails working with the communities you’re recruiting from in designing the study early on, and through the life of the project,” said Pajau Vangay, a fellow in the Biomedical Informatics and Computational Biology program at the University of Minnesota and researcher in Knights’ lab.

“Our project would not have been possible without using this method.” It gave the work an educational component, she said. “Many of these groups don’t have access to a lot of scientific knowledge, even the concept of a gut microbiome… it allowed us to spread the knowledge.”

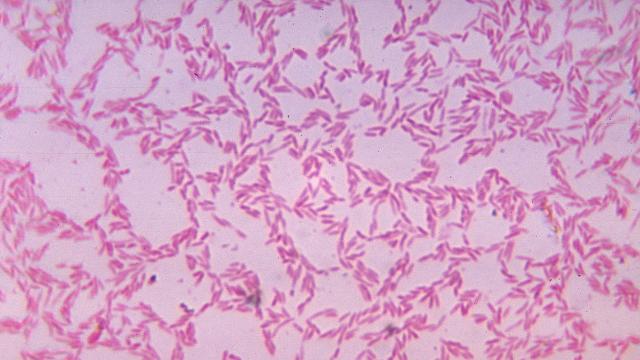

Analysis of the stool samples showed that levels of Prevotella bacteria in the immigrant microbiomes went down, and levels of the western-associated Bacteroides bacteria went up. The ratio tipped more and more in favour of Bacteroides from the first- to second-generation of immigrants.

A different microbiome doesn’t necessarily mean a worse one, but their microbiomes didn’t just change — the mixture of bacteria that inhabited their guts became significantly less diverse. “We expected that there would be some loss of diversity when people came to the US, but we didn’t know if it would be enough for us to actually observe,” Knights said.

“We were surprised to see how clear the signal was.” Second-generation immigrants saw an additional drop off in their microbial diversity, he said. “They’re not significantly different from people whose families are from the United States.”

That’s important because lack of microbiome diversity is associated with many health conditions, like obesity. “There seems to be a universal association with loss of diversity with disease,” Knights said. Notably, obese individuals in the study had the lowest levels of microbial diversity.

While changes in diet helped explain some of the shifts seen in the immigrant microbiomes, it didn’t account for all of the variation. That wasn’t necessarily surprising, Vangay said, partly because the groups studied were refugees going through a dramatic lifestyle change. Apart from changes in diet, they experienced shifts in environment and water sources, new medications, and changes in their mental states — all of which can also affect the microbiome.

It’s important to note that the study was not able to determine if the changed microbiome actually contribute to metabolic disease in this group. “Answering that is an obvious direction for future work,” Knights said.

Understanding the factors that transform the immigrant microbiome so quickly might help researchers develop ways to stave off that transition, particularly if future work shows that a changed microbiome does, in fact, have a negative health effects. “And if we could figure out how to prevent that from happening in immigrants, it might teach us something about how to keep other group’s microbiomes healthier as well,” Knights said.