Devil Man Crybaby. Night Is Short, Walk on Girl. The Tatami Galaxy. Keep Your Hands Off Eizouken! Masaaki Yuasa’s directorial work has almost become defined by its surreal. His latest anime is unlike anything you’d expect from the director’s oeuvre… but not in the way you’d expect.

Netflix recently released Japan Sinks 2020, Yuasa’s latest collaboration with the animation studio he co-founded with Eunyoung Choi, Science Saru (and before retiring as its president). It’s an adaptation of the classic 1973 sci-fi disaster novel Japan Sinks, by Sakyo Komatsu. The 10-part series follows the MutÅ family ” Filipino mother Mari (Yuko Sasaki/Grace Lynn Kung), her Japanese husband KÅichirÅ (Masaki Terasoma/Keith Silverstein), middle school athletics hopeful Ayumu (Reina Ueda/Faye Mata) and youngest child GÅ (Tomo Muranaka/Ryan Bartley) ” as they are caught up in a series of devastating earthquakes that rock the Japanese archipelagos, effectively sinking the majority of the country.

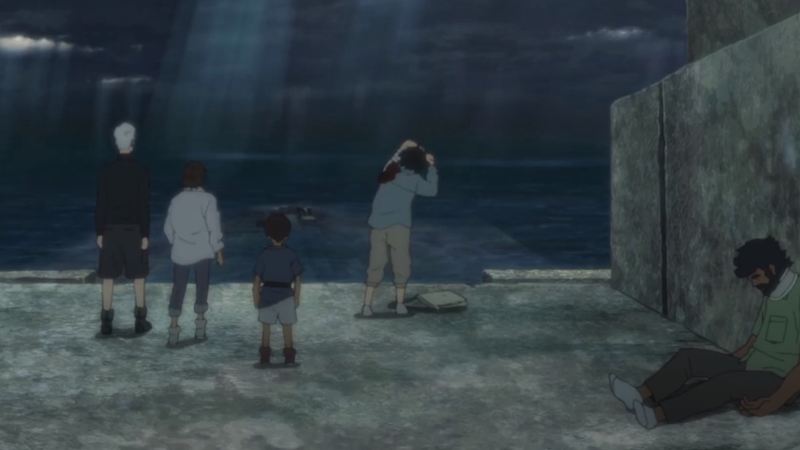

It’s a disaster epic in every sense of the genre, as the MutÅs first have to find each other and then spend the rest of the series desperately fleeing one earthquake after another, every respite only temporary, every moment of peace inevitably torn asunder by horror. It is an exhaustive experience to watch, not in the sense that you might typically expect from a disaster-porn movie, but in the more gruelling meaning of the word: I found it genuinely difficult to binge Japan Sinks in the way Netflix typically wants its audience to consume originals on the platform by dropping them all at once. It is so emotionally uncompromising, so relentless in its vision of despair, that it becomes a fascinating slog.

Japan Sinks is shocking on two levels. It’s rooted in sci-fi elements for the nature of its natural disaster-rampant world. But aside from that base premise (and the fact that it’s set in an alternate reality where the Japanese 2020 Olympics were actually going to go ahead, I guess), it’s perhaps both Yuasa’s biggest project as a director yet and also his most grounded. There is nothing fantastical about Japan Sinks in the way there has been in Yuasa’s most lauded works ” no flights of fancy, no moments of imagined peace or drama amid the very real horrors of the world that encircles Ayumu and GÅ. Japan Sinks shocks because of just how absent the sort of visual storytelling is which has made Yuasa one of the most interesting anime directors around right now.

[referenced url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2020/07/japans-newest-bullet-trains-can-keep-running-on-battery-power-in-the-event-of-a-disaster/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/14/swg4axc3snv0z2b5k6dh-300×169.jpg” title=”Japan’s Newest Bullet Trains Can Keep Running on Battery Power in the Event of a Disaster” excerpt=”Japan’s bullet trains are quite possibly the world’s most punctual form of transportation, and the safest way to hit speeds of over 322 km/h without leaving the ground. The newest version, the N700s that’s now running on the country’s Shinkansen Line between Tokyo and Osaka, is also the first to…”]

That’s not to say Japan Sinks looks particularly boring or anything ” there’s a befitting sense of scale to its destruction, and its ruined cityscapes would be immaculate if not for the fact they’re being torn apart on a regular basis. There are moments of beauty in the show and Yuasa’s directorial eye saves them for both moments of respite and, in morbid fashion, the scope of the disaster that befalls our protagonists almost ceaselessly.

There are some absurdities, but rather than in the eclectic, visual sense, they’re saved for the complexity of the ragtag group of survivors the MutÅ family finds themselves caught up with as they trek across what’s left of mainland Japan. There are high schoolers, kindly next neighbours, xenophobic yet archery-skilled shopkeepers, foreign tourists caught up in the calamity, and, in perhaps the most oddball character of the show, KITE (Kensho Ono/Aleks Le), a paragliding Estonian YouTuber. Japan Sinks finds its weirdness not in the visual splendor that Yuasa has heavily trafficked in in the past, but in the complexity of its unlikely protagonists, people from all walks thrust together to try and survive a nightmare from which none of them can seemingly wake.

This starkness is jarring for those coming into the show expecting something along the lines of a Devilman Crybaby, a show likewise as dark as Japan Sinks but to an explosive, almost comically extrapolated level, where its violence and despair is amplified by its overt, supernatural elements. Japan Sinks is just as brutally, shockingly violent, and is so regularly and repeatedly, but it’s made much more shocking to consume compared to something like Devilman by the fact that it’s rooted in such an unyielding realism. This isn’t a nihilistic demonic apocalypse, it’s everyday, normal people being crushed by debris, swept away by tides, or taken out in myriad other moments of accidental tragedy.

Death is constant in the world of Japan Sinks, it is always traumatic and emotional but rarely is it ever particularly dramatic. No one in Japan Sinks‘ cast is safe, so death is never built up to as some emotional sacrifice or heroic climax to a disaster sequence. It’s not treated lavishly. It just… is. People are there one moment, and then they are not. The MutÅs and their fellow survivors, who dwindle across the 10 episodes of the show, just have to deal with that brutal fact, time and time again.

And that, really, is what defines Japan Sinks, for better or worse. There’s an emptiness you’re left with by the time you get to the final episode, if you even get that far because it is so starkly brutal to the point of repetition. The show’s greatest tool ” the fleeting nature of its casts in the face of unfathomable disaster ” is turned to with such regularity that you’re left numb to its effects after the first three or four shocking, out-of-nowhere deaths. There is no escape in much of Japan Sinks, of either the surreal or real sense, which makes it both Yuasa’s most surprising work so far and yet also, a peculiar way, simultaneously his least interesting one.

There’s something to be said in Yuasa trading in lush spectacle for stark realism, but in keeping some of the violent brutality of prior work like Devilman Crybaby without that spectacle, you’re left with an experience that strikes a much bleaker tone ” even as it slowly but surely bends towards some semblance of hope for what remains of the cast as it draws nearer to its conclusion.

Once you get over that, Japan Sinks is not the kind of visually mindbending story you might have come to expect from the director. What you’re left with is a bleak, grim story of survival, one that is, at times, worth bearing that bleakness for. However, it might be better to go into it much more prepared than Japan Sinks‘ protagonists are for the calamity that lies ahead.