A once-in-a-century “climate anomaly” exacerbated the awful conditions along the Western Front in Europe during the First World War, according to new research. This unusual weather may have also amplified — and possibly even initiated — the catastrophic 1918-19 flu pandemic, exposing an underappreciated threat posed by climate change.

New research published in GeoHealth describes the impact of a six-year climate anomaly on World War I and the 1918-19 influenza pandemic. The unusual weather, which occurred from 1914 to 1919, included torrential rain and particularly cold temperatures, making a bad situation even worse, according to the study, led by climate scientist and historian Alexander More from Harvard University.

That extraordinarily awful weather worsened the war and the pandemic is entirely plausible, but the new research also proposes — albeit speculatively — that the climate anomaly caused the pandemic to start by altering the migratory behaviour of ducks, notorious carriers of H1N1, a type of influenza virus.

The First World War is famous for its dreadful environmental conditions, particularly along the Western Front, which stretched from the beaches of the English Channel to the Swiss mountains. Soldiers fighting in France and Belgium struggled through the incessant rains and unusually cold weather, particularly at the battles of Verdun, the Somme, and Passchendaele.

The constant shelling by both sides created vast wastelands, and when the rains came, these tortured fields became dangerous quagmires. Soldiers stuck in mud holes often needed help to escape, but some weren’t so lucky. Recounting his experience at Passchendaele in 1918, Canadian veteran George Peakes said, “many wounded men slipped into those shell holes and would have been drowned or suffocated by the clammy mud.” The role of mud along the Western Front cannot be overstated, as it created dangerous conditions, reduced the mobility of soldiers and horses, made it hard to move equipment like artillery, and diminished the quality of life in general.

Indeed, the excessive rain made life intolerable in the trenches. Soldiers, standing for days in the water, couldn’t keep their feet dry, resulting in trench foot, which is the term still used today to describe this painful condition. At the same time, the uncommonly cold conditions contributed to rashes of frostbite and the further deterioration of the soldiers’ health.

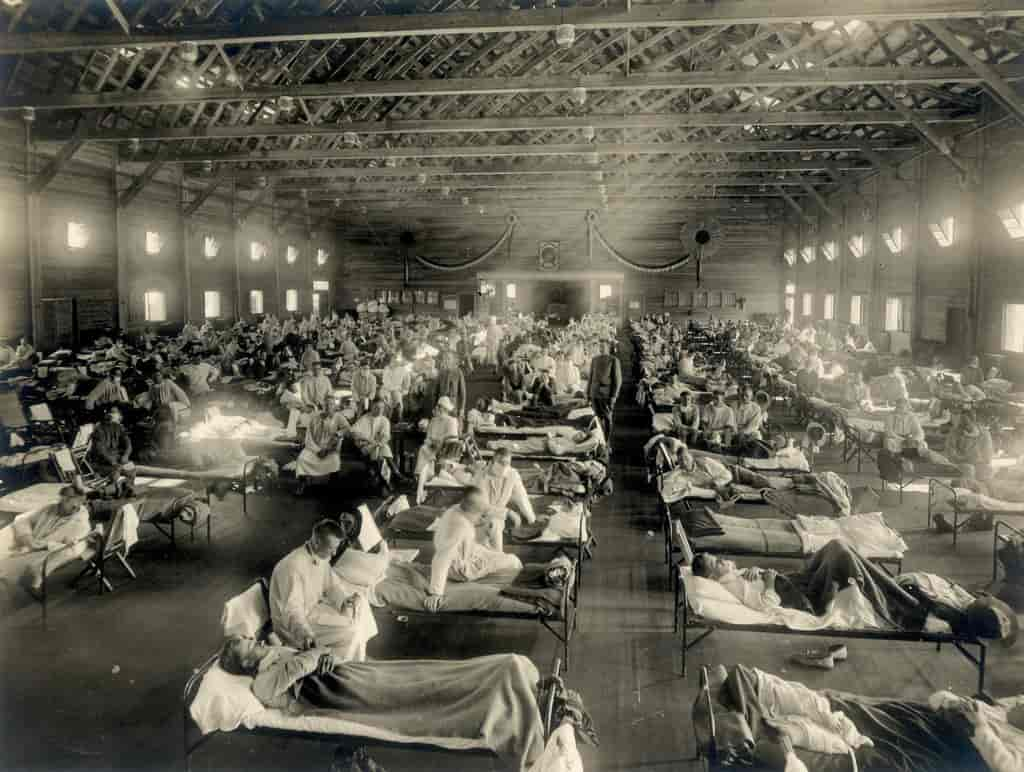

As the war was winding down, an awful pandemic was picking up. The H1N1 pandemic of 1918-19 is often referred to as the “Spanish Flu,” which is rude by modern standards and also inaccurate, as scientists and historians don’t actually know where this pandemic got started. What we do know is that the disease picked up steam during the spring of 1918 and hit with full ferocity in the fall of the same year. By the time it ebbed during the following year, the pandemic had taken somewhere between 50 million to 100 million lives.

And thus ended “several years of unprecedented mortality throughout Europe,” wrote the authors in their study. The team launched its investigation to see if weather during WWI was truly odd, and if so, if environmental conditions played a role in shocking mortality during the war and pandemic. The results of their work suggests it likely did.

To get started, the researchers extracted an ice core from the European Alps, allowing them to reconstruct climate conditions from 1914 to 1919. This data was then compared to mortality rates experienced in Europe during the same time period, as well as historical accounts of torrential rains on Western Front battlefields.

The scientists found correlations between peak periods of mortality and punctuated periods of cold temperatures and heavy rain, namely unusual weather episodes during the winters of 1915, 1916, and 1918.

“The data presented here show that extreme weather anomalies captured in [ice cores] and reanalysis records brought unusually strong influxes of cold marine air from the North Atlantic, primarily between 1915 and 1919, resulting in unusually strong precipitation events, and that they exacerbated total mortality across Europe,” wrote the authors in the paper.

This kind of climate anomaly, they said, happens about once a century. That it happened during the biggest war humanity had seen up until that point, while also coinciding with some of the war’s biggest battles, is unbelievably bad timing.

It’s also possible that this awful weather ushered in the pandemic, the authors argue. The excess precipitation, along with cold ocean air hanging over the Western Front, may have altered the migratory patterns of mallard ducks. This is significant because mallard ducks are “the primary reservoir [source] for the H1N1 avian influenza virus,” according to the study.

So instead of migrating to Russia per usual, many mallards stayed put, hanging out near civilian populations, military theatres, and domesticated animals, the authors speculate. Through their faecal droppings, these ducks could have contaminated bodies of water sourced by humans and other animals. Intriguingly, excessive rain during this period produced more bodies of water than usual, amplifying an already bad situation. As the authors write, the resulting “interplay of environmental, ecological, epidemiological, and human factors,” can account for the exaggerated death toll experienced across Europe during this time period.

This theory, that ducks sparked the pandemic because they couldn’t migrate, is super, super speculative, as the authors themselves admit.

“I’m not saying that this was ‘the’ cause of the pandemic, but it was certainly a potentiator, an added exacerbating factor to an already explosive situation,” said More in an AGU press release.

In the same press release, Philip Landrigan, director of the Global Public Health Program at Boston College, said it’s “interesting to think that very heavy rainfall may have accelerated the spread of the virus.” A lesson learned from the covid-19 pandemic is that “some viruses seem to stay viable for longer time periods in humid air than in dry air. So it makes sense that if the air in Europe were unusually wet and humid during the years of World War I, transmission of the virus might have been accelerated,” said Landrigan, who wasn’t involved in the new study.

“I think it’s a very credible, provocative study that makes us think in new ways about the interplay between infectious diseases and the environment,” he added.

[referenced id=”1225763″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2020/06/volcanic-eruption-in-alaska-may-have-sparked-political-turmoil-in-ancient-rome/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/25/gykhlg3shhez2ekhkc3h-300×169.png” title=”Volcanic Eruption in Alaska May Have Sparked Political Turmoil in Ancient Rome” excerpt=”An unusually powerful volcanic eruption in 43 BCE has been linked to political upheaval on the other side of the globe, including the fall of the Roman Republic and the Ptolemaic Kingdom.”]

This isn’t the first study to come out this year claiming that environmental factors had a bearing on historical events. Research published in June pointed out that awful weather triggered by a volcanic eruption in 43 BCE just happened to coincide with the demise of the Roman Republic and the Ptolemaic Kingdom. History happens, but sometimes environmental factors can make it extra-happen.