In the small town of Grosse Tête, Louisiana, a Bengal-Siberian hybrid tiger named Tony lived 17 wearisome years confined to a chain-linked, concrete-slabbed cage. His bloodline hailed from halfway across the planet, where tigers prowled as apex predators in the depths of Rajasthan’s subtropical jungles and Siberia’s snow-blanketed birch forests.

Bengal tigers have called the Indian subcontinent home for well over 10,000 years. Meanwhile, the largest of the subspecies, the Siberian tiger, have trekked parts of East Asia and Russian Far East for perhaps longer. In contrast, Tony spent nearly his entire life as an exhibit for drivers and passersby, just off Interstate 10, at a truck stop and gas station. The stench of diesel fumes and the racket of trucks were part of Tony’s daily life until he was euthanised in 2017.

Unfortunately, Tony’s life story is not unique. A broader, unchecked trend of big cat possession is afoot in the U.S. From coast to coast, an untracked number of private citizens own big cats, amongst other wildlife. “Roadside zoos” are springing up, profiting from wildlife exhibits and paid encounters. Amidst the covid-19 pandemic, roadside zoos are still in operation despite the risk of zoonotic disease spread.

“We know that tigers are susceptible to covid-19, so right now, they are exposed to an even greater risk as some of these cub petting operations remain open during the pandemic,” said Meredith Whitney, a wildlife rescue program officer at the International Fund for Animal Welfare.

The danger of further zoonotic disease spread was unchecked before the current pandemic and remains so. “What it really points to is that this is a problem: to take big cats or any other kind of wildlife, and use them for human entertainment and human interaction… inevitably, these interactions between humans and big cats are going to increase the chances of zoonotic disease transmission,” said Alicia Prygoski, legislative affairs manager at the Animal Legal Defence Fund.

Public health risk is exacerbated by the innumerable amount of captive big cats in the U.S., which has expanded due to rampant breeding.

Other big cats such as jaguars, cheetahs, and lions are also exhibited at roadside zoos across the country, but tigers are the most common. The industry is largely unregulated at the state and federal levels, which creates significant difficulties in gaining a tally of all the big cats in captivity.

Conservative estimates suggest that 10,000 to 20,000 big cats are captive in roadside zoos, menageries, and people’s homes. Of that number, a low-ball estimate of 7,000 are tigers alone. Netflix’s series Tiger King shined light on just a corner of this big cat world that operates in the shadows.

Even the lowest estimate of U.S. captive tigers is still greater than the estimated 3,890 remaining in the wild. While some subspecies like the Bengal tiger are finally repopulating and following an upward trend, most tigers’ story is grim.

Once roaming from the reaches eastern Turkey to Java’s shores, three of the nine original tiger species have gone extinct, and those that remain are hanging on by a thread. Over the past century, wild tiger populations have declined by 95 per cent. Indeed, conserving these big cats is at a critical tipping point.

As wild tigers and other big cats are in dire need of protection in their native habitats, their captive counterparts on our distant shores are harming their very conservation. From potentially feeding the illegal trade in tiger parts to impacting individual livelihood, the U.S. captive-keeping of big cats has a rippling effect that is now gaining recognition. And as increasing scientific evidence shows, ignoring animal welfare undermines species conservation.

Roadside zoos and cub-petting tourism

As apex predators, tigers have evolved to cover vast territory, typically grasslands and forests. In Bangladesh, a tiger requires 8 square miles (20.8 square kilometers), while in Siberia, a tiger defends an area that can reach up to 997 square kilometres.

The largest of the big cats, a tiger, can size up to 3.7 metres in length and weigh up to 300 kilograms.

Today, these powerful predators are kept in a neighbour’s backyard or confined in a shaky, makeshift cage smaller than a one-car garage. They are paraded around in the cramped enclosures of a roadside zoo, alongside droves of other exotic wildlife people pay to visit.

In the last several decades, across various parts of the U.S., a tiger and big cat cub breeding cottage industry has emerged. One of the largest of these operations was the backdrop to the Netflix docuseries Tiger King.

In the early days of the covid-19 pandemic, with lockdowns in place, Americans became engrossed in the human drama that unfolded on this Netflix docuseries. For the first time, across the country, the public was exposed to captive tiger keeping and their exploitation taking place in the U.S.

However, the professionals working on the frontlines of tiger rescues and big cat protections believe that the docuseries missed the mark.

“The unfortunate part of Tiger King is the oddity and craziness of the humans, and their conflict there became the overarching theme,” commented Angela Grimes, the chief executive officer of Born Free USA, “and what was really missed in the show, on the part of the viewers, is the animal cruelty. That seemed to be secondary to the main storyline of the humans.”

Fundamentally, the cruelty inflicted on the animals lies in the ease with which one may become a big cat exhibitor. Alicia Prygoski of ALDF explained, “when we’re talking about obtaining a licence to exhibit big cats, it’s very easy to get that initial licence, and it’s relatively inexpensive.”

“Those looking to obtain a licence should have to show that they’re able to provide long-term care to their animals, as well as veterinary care, psychological stimulation, and adequate space,” Prygoski continues, “but unfortunately, there is a really low bar currently for obtaining a licence… and it results in horrifying abuse and neglect of animals at roadside zoos.”

These facilities are reaping a profit from paid interaction sessions and paid “tiger selfies” and other Instagrammable photo ops with wildlife — these rapid-fire sessions are taxing on both the cats’ physical and mental health.

“When someone takes a prom photo with a fully-grown tiger, that tiger may have to be drugged in order for them to be sedate enough to allow that to happen,” said Angela Grimes, the chief executive officer of Born Free USA. “Whether they are or they aren’t [drugged], that is a very dangerous situation for the human… and the conditions that those animals are kept in, the way they are treated, often beaten and subdued, so that they will act a certain way around humans is not their natural behaviour.”

Grimes added, “this is a volatile situation that is all about profit, it’s not concerned for the animals, and it’s not concerned for the humans.”

The physical abuse endured by tiger cubs bred in cub petting facilities results in life-long health issues.

“Separating tiger cubs from their mothers mere days or even minutes after birth is very stressful and traumatic for the cubs and the mother,” Meredith Whitney of IFAW said. “When cubs are pulled to be used for cub petting businesses, they are often [intentionally] undernourished, so they stay smaller longer and stay hungry for more paying customers to feed.”

In tiger rescues conducted by IFAW, Whitney has found that “cubs are often sick and malnourished” and that both “cubs and adults show evidence of metabolic bone disease which results in bone deformities, fractures, organ failure, and sometimes death.”

The Humane Society conducted three undercover investigations of cub petting facilities. The findings were consistent. Extreme and persistent animal abuse involving round-the-clock handling for clients, physical punishment by keepers, filthy enclosures, medical neglect, malnourishment, intentional food deprivation, and untreated contagious infections. At one facility, a 3-week old tiger cub named Sarabi, infected with ringworm, was handled by 27 people just after she arrived from a 19-hour car ride.

The process of breeding new tigers is often relentlessly abusive to the mothers as well. “Tigers used for breeding are forced to give birth two to three times a year, compared once every few years in the wild,” said Alicia Prygoski of ALDF.

The conservation lie

A majority of facilities attempt to persuade visitors that they are conserving tigers. These zoos and roadside attractions make the pitch that paying to visit can save the species from the brink. But the reality is far different.

“Some places claim that it is a conservation service that they provide by breeding these animals,” said Kathy Blachowski, program manager at the Big Cat Sanctuary Alliance. “These exotics that are bred and born in the U.S., they in no shape or form, could be released into the wild.”

Leigh Henry, director of wildlife policy at WWF, the largest global conservation organisation, attested that this form of “breeding tigers in captivity is not conservation.”

Some big cat encounter facilities, like Doc Antle’s Myrtle Beach Safari — one of most prolific tiger breeders in the country who also appeared in Tiger King — claim that they are not just contributing to conservation but conserving the rarest of tigers, the white tiger.

“These places play on customers by claiming that they are ‘royal Bengal white tigers,’ that they are ‘very rare’ or ‘nearly extinct,’ but they’re just a colour variation of a Bengal tiger. They don’t or rarely naturally occur in the wild. And to produce them captivity, they have to be very, very heavily inbred, which leads to a lot of genetic deformities,” said Lisa Wathne of the Humane Society.

To breed a white tiger takes a lot of forced inbreeding of father to daughter, brother to sister, and the like. While that may yield a tiger with a striking coat, it also results in serious health issues.

“Some of them have misformed hips, a lot of them have issues with their bone development, many white tigers are cross-eyed and have problems with their vision,” explained Blachowski of BCSA.

Many of these inbred tigers are born with unfavourable features, deformities, and illnesses. They quickly prove unusable for visitor exhibition, and most often, exhibitors promptly slaughter these ‘imperfect’ tiger cubs.

“Doc Antle in South Carolina has admitted that he routinely euthanises any white tiger cubs born cross-eyed,” Wathne said. Despite it being illegal, he and others get away with exterminating big cats. This outright slaughter is a failing on the part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which has perpetually abandoned their role to enforce the Animal Welfare Act.

In addition to the evident animal abuse issues at hand, the conservation value is nonexistent, despite what roadside zoos claim. Many tigers are crossbred––like Tony at the truck stop––as well as inbred and undernourished.

“Generic tigers cross two or more tiger subspecies, that’s not a tiger you would find in the wild. Professionally run zoos are breeding for conservation purposes and with very careful consideration for their genetics,” Tracie Letterman, vice president of federal affairs at the Humane Society Legislative Fund explained.

The appeal of these roadside zoos and encounter facilities is compelling for those who want to get up-close to a charismatic animal. And that much more enticing, with the false pitch of contributing to species conservation. “These places lie to consumers constantly and take advantage of people who are already inclined to love animals,” said Carson Barylak, campaigns manager at IFAW.

“It sounds like the best deal in the world — if you can both be kind to a tiger in your presence, have the fun, and the Instagram likes of having a photo snuggling with a tiger, and presume that you’re helping to protect its wild counterparts, of course, that’s convincing to people,” Barylak said.

Like most other animals, tiger cubs grow quickly. As predators, they rapidly gain strength and become dangerous at a relatively young age.

To exhibitors, a cub’s utility exists for only a short time, and after twelve to fourteen weeks of age, they can no longer be handled by paying visitors. Lisa Wathne of the Humane Society said, “but of course the breeding keeps going because they’ve got to keep supplying more and more cubs for these very lucrative photo ops.”

What happens to most cubs once they outgrow their use at cub petting facilities is mostly unknown. Some “spend the rest of their lives in tiny cages, at roadside zoos, or pseudo-sanctuaries,” explained Wathne, while others are “shunted into the pet-trade,” and “some of them are probably killed.”

Meanwhile, it is speculated that “others end up on the black market to be sold for their body parts,” said Ben Williamson, programs director of World Animal Protection. While this yet to be documented, it is an overarching concern for big cat conservationists.

“Under this poor regulation, America’s captive tigers could easily be filtering into illegal trade and perpetuating or stimulating consumer demand for their parts and products,” explained Leigh Henry of WWF.

At first glance, tiger and big cat keeping in the U.S. appear to be an isolated issue, but in reality, it is impacting even their relatives in the distant wild.

“It’s really just a very cruel cycle of breeding, exploiting, and then dumping of tigers––that ultimately, is the root cause of most of the problems we see regarding captive tigers in the U.S.,” asserted Wathne of the Humane Society.

The law

The cruelty inflicted on big cats at roadside zoos and exhibitor facilities is done so in direct violation of the laws meant to work together to protect wildlife––the U.S. Animal Welfare Act, the Endangered Species Act (ESA), and state cruelty statutes.

Currently, any facility that receives money in exchange for exhibiting captive animals must be licensed by the Department of Agriculture (USDA) under the Animal Welfare Act and comply with the law.

Tigers and lions are protected under the ESA, which prohibits the harming, harassing, and killing of these animals. “Harassment includes that they cannot annoy an animal to such an extent that it significantly disrupts the animal’s normal behavioural patterns,” Daniel Waltz, a staff attorney at ALDF, explained on a webinar regarding captive big cats.

Waltz expanded, “strong laws are only as good as their enforcement. And for many reasons, some I understand and don’t understand, federal and state government officials have been unable or unwilling to enforce the laws that are on the books.”

“The USDA records animal inventories when they inspect facilities that are open to the public, but those inventories only represent the animals that are seen by the inspector during the visit, not necessarily all of the animals at the facility,” Meredith Whitney of IFAW said. She also noted that the agency does not inspect facilities that are not open to the public, including private menageries and breeders.

The failings of the USDA became even worse in the past three and a half years.

“Back in early February 2017, the USDA purged thousands and thousands of records from its website,” including inspection reports and enforcement actions, said Delci Winders, director of Animal Law Litigation Clinic at the Lewis and Clark Law School.

The reasoning behind the data scrub is murky. Winders said it likely reflected the USDA trying to hide its own failings at enforcement long-term and the fact that things have gotten worse in recent years under the Trump administration.

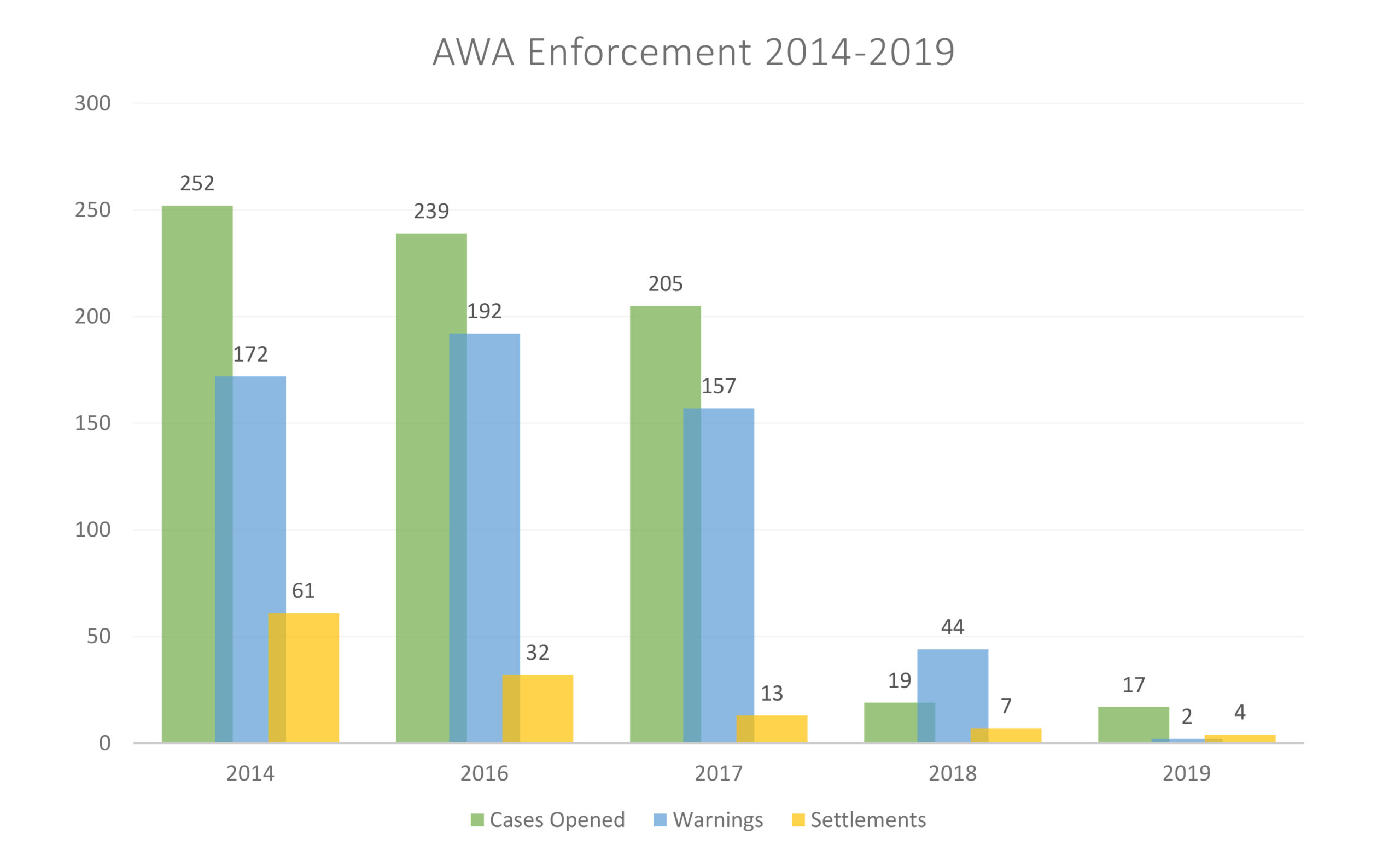

Between 2016 and 2019, USDA enforcement of the Animal Welfare Act dropped by 93 per cent.

Alongside a coalition of nonprofits, including PETA, Born Free USA, and the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, Professor Winders sued the USDA to restore their deleted records.

In May, they partially won that fight. “But the category where [the USDA officials] have not restored is enforcement actions. Nothing previous was restored from the enforcement actions; only new enforcement actions have been posted.”

Despite new inspections being made public, actual enforcement continues to weaken. At the end of July 2020, an inspection report was released for Jeff Lowe, the individual who acquired Joe Exotic’s zoo. “With a slew of horrific violations on big cats, his licence should have been suspended immediately,” Winders attested.

“When you look at the facts, animals are suffering,” Winders observed, “and their [the USDA officials] job is to protect these animals.”

Public safety

Privately held captive tigers and big cats interacting with people pose a public health and safety risk as well.

“Obviously, big cats are apex predators, and so they pose a serious safety risk, whether it’s to the public or even in the best of situations, such as AZA-accredited zoos, to the people who work with them,” shared Lisa Wathne. “One mistake can be all it takes for a fatality to happen or a very serious injury.”

Since 1990, the Humane Society has documented over 400 dangerous incidents involving captive big cats in 46 states and the District of Columbia.

“A lot of places like roadside zoos or places that breed big cats don’t even have proper containment for these animals,” said Blachowski of BCSA. “There are instances where exotics have gotten out because they [private keepers] do not have the proper containment for these animals, and put the public and first responders into harm’s way.”

One of the most dramatic incidents took place in Ohio in October 2011, known as the “Zanesville Massacre.” The tragic event put the community and first responders in danger when a man released 56 wild animals into the town, including tigers, lions, and leopards.

With zero training on how to handle a high volume of dangerous, wild animals on the streets, first responders had little choice but to shoot down the majority.

Similar cases of dangerous, exotic animals on the loose pop up around the country far too frequently. And first responders are often the first to get caught in the focus of a 3.66 m-long big cat predator. When a tiger breaks loose from its flimsy cage and runs rampant through the suburbs, or when a lion appears in someone’s living room, police find themselves face-to-face with a terrible situation.

“Police or fire officials are responding to a scene, and they don’t know that there’s a tiger in the basement in the house. It’s a danger they should not be exposed to and something they’re not trained for, and they shouldn’t ever have to be trained for,” explained Meredith Whitney of IFAW.

In response to the event in 2011, Ohio enacted more significant state restrictions on the ownership and breeding of dangerous wild animals.

In addition to outright corporal hazards, the handling of big cats and other wildlife poses another threat to public health: the spread of zoonotic disease from animal to human.

“With cub petting, there are different diseases that can be spread from these young cubs who have not been properly cared for and are interacting with the public,” said Kathy Blachowski of BCSA.

Given that the covid-19 virus spawned from human-animal contact, the perpetuation of these cub-petting roadside zoos and their continued operation amidst the current pandemic is acutely concerning.

“What the coronavirus has taught us is that we cannot neglect the disease transmission from wildlife animals any longer,” said Ben Williamson of World Animal Protection. “We’ve known for years that wild animals in stressful situations are just hotbeds for pathogens and potential disease risks, and we ignored it, and we didn’t do a thing about it.” Willamson concluded, “and now, the coronavirus taught us the hard lesson: that we can no longer ignore these variables.”

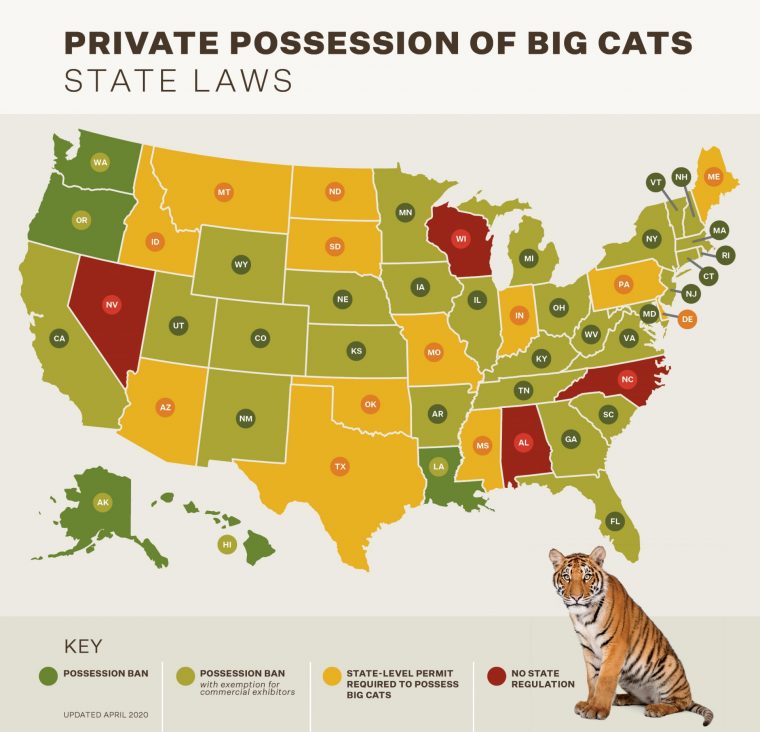

Regulations on big cat keeping vary by state. Some have strict laws, and some allow the practice to exist with no oversight. Six states in the U.S. have no statutes regarding keeping big cats captive, while 13 states allow big cats with a permit or licence.

“Right now, there is piecemeal legislation throughout different states. Some states have a total ban on possession; some states have no ban on possession. And there’s really no federal laws that accurately protect big cats and possession in the United States,” said Kate Blachowski of BCSA.

“Many states do have bans on private possession of big cats, but really we need a uniform federal law,” asserted Alicia Prygoski of ALDF.

There is a bill aiming to do just that.

Hope

In January 2019, U.S. House Representatives Brian Fitzpatrick (R-Pa.) and Mike Quigley (D-Ill.) co-introduced a bill known as the Big Cat Public Safety Act (H.R. 1380). If passed, this bill will amend the Lacey Act and create comprehensive federal legislation to regulate big cat keeping and ban public contact.

Rep. Quigley shared with Gizmodo that a decision on the bill may be imminent. “I suspect we will [vote] at the latest by the end of September.”

The House bill has 220 bipartisan co-sponsors and, in June, successfully passed the House Committee of Natural Resources.

Of course, amidst the pandemic, a lot of bills are taking a backseat. “While we are dealing with other critical issues, we want to deal with the humane issues on this and the safety issues that come with it as well,” shared Rep. Quigley.

The bill aims to restrict the possession and exhibition of big cats. If passed, it would ban direct contact between the public and big cats, effectively ending cub petting and interactive sessions.

“It would prohibit public contact, so petting and selfies, those activities would be prohibited,” explained Prygoski of ALDF. “By banning direct public contact, the Big Cat Public Safety Act will decrease the demand for cubs and thus decrease the number of big cats who are being bred for this cruel industry.”

“What we tried to do was to get something to pass as a major first step,” shared Rep. Quigley. “It prohibits the breeding of any big cat outside of accredited zoos or research-educational facilities. If you already have a cat, it would be required to register it with the USDA. And of course, it outlaws private possession of any of the big cats except at highly qualified facilities.”

By requiring people to register their big cats with the USDA, for the first time, the U.S. would gain a tally on just how many captive tigers and big cats exist across the country.

Given the recent shortcomings of the USDA relative to enforcement, some concerns arise on how effective the bill will be even if it does pass. Delci Winders, who sued the USDA on the 2017 data purge, said, “I’m thankful the Big Cat Public Safety Act gives significant responsibility assigned to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which has not shown these same failings.”

Those who already own a big cat would be able to keep them per the ‘grandfather clause.’ “It’s a gradual but effective transition, and it would prevent an immediate influx of big cats into sanctuaries,” explained Prygoski of ALDF. “This is the most common-sense way to handle the fact that there are thousands of big cats in private hands right now across the country.”

“There are those who initially said we should make it illegal even if you already have a [big] cat, which we foresaw as being a bigger hurdle at this point in time,” mentioned Rep. Quigley.

While some activists feel that this bill does not go far enough on imposing more significant restrictions on big cat keeping, Angela Grimes of Born Free USA argued, “it’s better to make this change to eliminate the private possession than to go for an all-out ban that has no hope of passing.”

The bill has garnered a wide range of support; however, more steps than just passing the House will need to occur. “Even if it passes the House, it still has not moved forward in the Senate, even though it’s a bipartisan measure,” explained Carson Barylak of IFAW.

It is unknown when the Senate version of the bill, which currently has only 23 co-sponsors, is set for a vote.

Having the bill pass will not only safeguard animal welfare and protect the public, but it will also aid tiger and big cat conservation in the wild.

“The Big Cat Public Safety Act would go a long way to ensuring that the U.S. minimises its risk of contributing to any illegal trade in tiger parts and products,” said Ben Williamson of World Animal Protection.

With the bill’s passing, the U.S. would regain some lost credibility on the world stage. “The magnitude of the big cat problem we have here in the United States is actually harming our diplomatic and conservation efforts abroad,” said Dylewsky of AWI.

In Asia and South Africa, tiger and lion farms threaten the species’ conservation efforts. “The U.S. government wants to close these kinds of farms because it’s integral to saving big cats in the wild,” said Williamson of World Animal Protection, “but we just have zero credibility on the issue because of our large, poorly regulated population of big cats in the U.S.”

“The current scale of captive breeding operations within tiger farms is a significant obstacle to the protection and recovery of wild tiger populations,” stressed Leigh Henry of WWF. “They undermine and complicate enforcement efforts and help to perpetuate the demand for tiger parts and products.”

Tiger and other big cat species are at risk from human pressures. And our actions in the U.S. are impacting tiger populations as far away as Sumatra.

“It’s all connected”

The United States’ lack of oversight on these apex predators’ trade takes a grim toll on their conservation and maintaining their place in the wild. Animal abuse, species conservation, public safety, and public health concerns are the various elements intersecting in America’s unresolved affair with possessing captive tigers and big cats in our backyards and as brazen forms of entertainment.

“It’s all connected: Our mistreatment of tigers reflects on our mistreatment of bats and pangolins,” said Ben Williamson of World Animal Protection. “We need to get our own house in order before we can condemn the treatment of wild animals by other countries. And the Big Cat Public Safety Act goes a long way to doing that and giving us the moral authority to go out there and shut down high-risk wildlife markets.”

Tony, the Bengal-Siberian tiger, at his truck stop in Louisiana, beside the clamor of 36 T freight trucks thundering near his cage, never knew what his recent ancestors savoured––the scent of freshly dampened grasslands after an Indian monsoon, the crackling sound of oak leaves beneath his paws in eastern Russia’s woodlands.

Tony’s story can become part of a forgotten past if we will it.

Instead, his story can be honoured by a collective effort that leads humanity to change course and transform how we interact with wildlife. Tigers, lions, and other exotic animals can live life as they are meant to––in the bounds of nature.

Rina Herzl is a freelance journalist covering pressing environmental and wildlife conservation issues. She has authored articles for Earther, Earth Island Journal, Mongabay, and EcoWatch.