Believe it or not, Disney’s software for kids used to be top-notch. In the early 2000s there were no bizarre CoCoMelon videos on YouTube or hundreds of phone-based apps to educate younger users, but there was high-quality edutainment software, and Disney (as well as several others) excelled at reaching the little demographic. I sampled much of it myself, usually as a result of one of my many trips to Office Depot with my parents.

KB Gear Interactive’s Disney SketchBoard debuted in 2000 alongside Disney’s accompanying creative suite Magic Artist Studio. Billed as the “animation station for kids,” it was a one-of-a-kind alternative to pricey graphic tablets marketed toward children. Its stylus-based interface offered a way for kids to draw, sketch, and paint their own works of art on the computer without messy art supplies. The 7 x 5-inch tablet boasted “256 levels of pressure sensitivity” as well as 1000 lines per inch resolution. Those numbers may have been impressive back then, but now a Wacom Intuos dwarfs them. Try 4096 pressure levels and 2540 lines per inch in 2021!

While there were plenty of kid-centric art suites like Pokémon Project Studio or Looney Tunes Photofun, this appears to have been the only drawing tablet for kids on the market at the time. Its manufacturer is no longer in business, but the tablet can still be found extremely cheaply on eBay, if you’ve got a PC with a serial port to run it.

But in 2000, serial ports were on every PC, and when I went with Mum and Dad to Office Depot one fateful day, I zeroed in Disney’s SketchBoard. More than just a piece of software, it was a peripheral that would soon become instrumental to just about every facet of my PC usage.

Featured prominently on an extra-wide package was a blue and green tablet that featured a jovial Mickey waving around a paintbrush dripping with rainbow hues. In bright blue letters, the package read “SketchBoard Studio,” with a splash of yellow paint that announced the package came bundled with Disney’s Magic Artist Studio. With one look at the box, I knew I had to have it.

I knew what KidPix was. I knew from the clean linework from some of my favourite artists online that, as fun as sketching my favourite anime characters in Crayola sketchbooks were, digital art was the way to go. Thus began my campaign for Mum and Dad to pick up the SketchBoard for me. I was unsuccessful for weeks, until one shining day rolled around. Office Depot “marked down” the SketchBoard to 40% off its usual price. Mum acquiesced. I yanked the peripheral off the shelf and tore into the package as soon as I got home — then promptly asked Dad to install it, because its serial port was too frustrating for me to contend with, despite being 13. I preferred plugging something in to screwing in two additional pins, too.

The SketchBoard was a phenomenal entry into the digital art world. It felt like learning how to use a PC all over again with all the possibilities it brought with it. I was happier than the first day I laid eyes on it, and holed up in the computer room for hours at a time with it.

The tablet came with a special overlay that corresponded to the icons on-screen. It also added an unnecessary layer to the already bulky tablet that made it difficult to complete all the actions I wanted to on-screen. So I took the overlay off and realised the tablet worked much better sans any additional plastic impedances.

Magic Artist Studio was interesting enough. I had seen enough art programs to appreciate that Disney’s attempt at kid-friendly Photoshop was actually a valid and productive attempt at introducing kids to the joys of photo editing software. You could draw a series of lines that would animate themselves into a tangle, paint with licorice-like media, and splash around with digital watercolors. It had everything a kid could want to dabble with, and then some, with some kooky sound effects to boot. But it ultimately didn’t hold my attention. I knew what I wanted to do with the SketchBoard, and that was drawing my own manga. All I needed for that was Photoshop, so I got going as soon as I laid out a story plan.

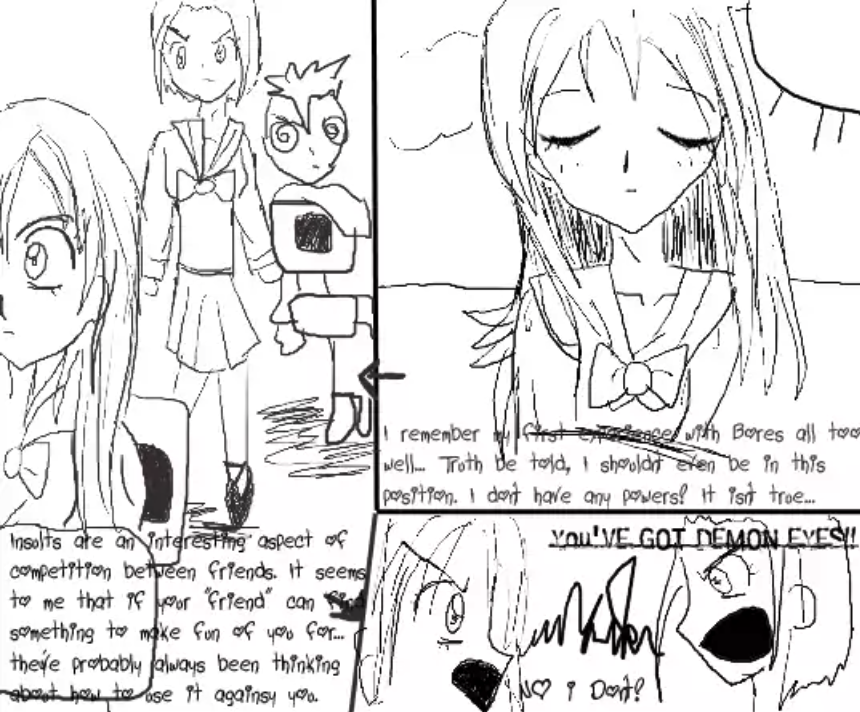

I wanted into the industry. Badly. “Fade” was born out of my desire to create my own magical girl manga, given my love for Sailor Moon and Princess Gwenevere and the Jewel Riders. I’m still unsure what I was going for, but I knew I wanted a supernatural adventure starring “the beautiful heroine Fade,” who fought against spirits called “Bores.” I also knew I didn’t want to have to draw many bodies. Those were hard.

I got to work creating two short “issues” with my SketchBoard and uploaded them to my personal website at the time, feeling so accomplished I could burst. Granted, it was 2003, so my personal site was more of a collective for my shrines to Sailor Iron Mouse, the Powerpuff Girls’ Buttercup, and Dragon Ball Z’s Vegeta.

No one ever really saw the pages except my immediate friends and family, but when they did, they all asked me the same thing: “How did you do this on the computer?” And I was so thrilled to share my little “secret” with them. No one else I knew had a SketchBoard or anything like it, so when I felt especially giddy about my creations I said it was a secret.

But I realised at an early age I was a writer, not an artist, and my desire to create art soon waned. As the years flew by, I continued to use the SketchBoard for a myriad of purposes. At the height of MySpace’s popularity, I used it to trace my friends’ photos and call them “portraits” they could use as profile pictures.

The entrepreneur in me charged them a small fee for my services. I sent handwritten notes to family and friends via email since I didn’t always have stamps handy for snail mail. And I learned the unique joys of using a stylus as an alternative mouse when my wrist began to hurt.

At some point, after seeing how much use I regularly got out of the SketchBoard, my parents surprised me with a very basic Wacom tablet as a birthday gift. It came with a special mouse and stylus, and the tablet itself could be customised by adding your own photo beneath the plastic casing. I rejoiced, as the Wacom offered much more precision and better performance than the SketchBoard ever could. Though it offered a smaller canvas, it lessened the time it took to create clean lines, and there was less input lag. Times had been changing, and the tablet world had changed with it.

So at some point I wrapped up the SketchBoard and put it away in my desk drawer. It was a bittersweet moment that I remember nearly choking up at because it felt like the end of an era. For years, the SketchBoard languished there after I had moved on to the Wacom. I saw a few iterations of the SketchBoard (mostly different retail packaging, from what I could tell), but it had disappeared from shelves about three years before I even received my Wacom. And these days, thanks to the emergence of smartphones and tablets, you don’t need a special device to make art wherever you go.

Following the SketchBoard’s disappearance, I saw an overall decline in kids’ PC peripherals in general. In the years following my dalliances with the digital drawing tablet, I rarely saw the wacky experiences promised to children in the Office Depot aisle I had when I first saw the SketchBoard package. I remember the bundles that let you create your own Barbie outfits or your own sticker nails. They seemed to vanish just as quickly as the SketchBoard did. It seemed audiences may have been looking for something different, more grown up sooner than I realised it.

While the Wacom improved my digital art experience tenfold, when I chose to use it, I still missed the whimsical blue and green Disney tablet’s colour scheme. I missed Mickey’s smiling face. In some ways, it felt like the transition from whimsical childhood into clean, clinical adulthood. And I still, to this day, miss my SketchBoard and the carefree days I spent with it.