Derpy from the side and hellish from below, the lamprey is the bane of the Great Lakes fisheries industry. A jawless, bloodsucking fish, the lamprey is often considered an ancestral early vertebrate for its rudimentary morphology and its larval life stage. Now, a team of researchers has authored a new study about fossilized lamprey larvae from the Devonian Period that they say shows lamprey evolution occurred differently than previously thought. This would mean we’d need to change our vertebrate origin story.

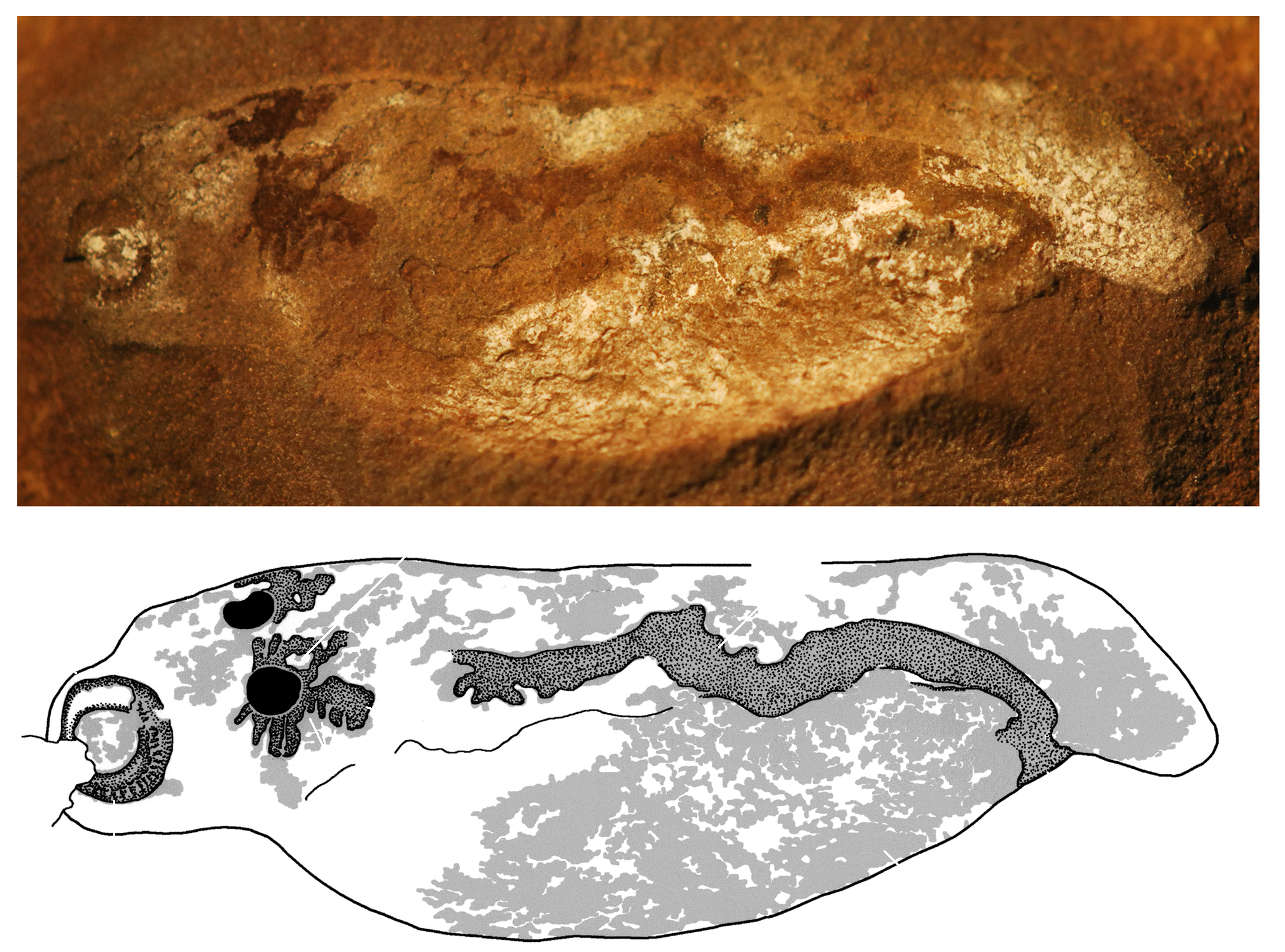

The researchers’ paper was published on Wednesday in the journal Nature. Their argument hinges on the lamprey life cycle. Modern lamprey larvae, called ammocoetes, are blind filter-feeders, which later transform into their noodly, predatory adult selves. Biologists and paleontologists alike have seen that ammocoete larval stage as a relic of early vertebrate evolution, and a sign that lamprey could be relied on as a living fossil that helps explain where all backboned animals came from. But the recent team describe baby lamprey fossils that are not ammocoetes — these fossils look just like smaller versions of adult lampreys — suggest that that larval stage was a later evolutionary adaptation, one unique to lampreys.

“Now, it looks like the lampreys are the weird ones,” said Tetsuto Miyashita, a paleontologist at the Canadian Museum of Nature and lead author of the paper, in a video call. “[The lamprey] looks primitive, more primitive than these extinct jawless fishes. But it was the other way around.”

Miyashita’s team describe four different species of ancient lamprey from Africa and North America, ranging from 360 to 310 million years old. Back then, the localities in Montana, Illinois, and South Africa (where the eel-like lampreys were excavated) were shallow seas; a different habitat from the freshwaters most lamprey wriggle in today.

The non-ammocoete fossil lamprey were not some smaller group of adult lampreys, the team says, as some of the fossilized fish even have yolk sacs still attached to their bodies. If that was just at one site, “we would have thought that we were looking at this really weird, specialised, extinct lamprey lineage that did its own thing and maybe lost the filter-feeding larval phase,” Miyashita said. “But species after species after species, across four different lineages of fossil lampreys, they show the same thing.”

The authors propose that the ammocoete larval stage was an adaptation the lamprey developed to move into the freshwater environments they now thrive all too well in. Over the 20th century, numerous efforts have been made to control the invasive lamprey population in the Great Lakes. First observed in Lake Ontario in 1835, the lampreys spread into the other great lakes in the mid-20th century. Now, the established population wreaks havoc on the lakes’ trout, whitefish, ciscoes, and other fish species, latching onto them with their suckers, eventually killing them. By the 1960s, the annual fish catch from the Great Lakes was 2% its previous average; a dramatic nosedive attributed to the lampreys.

For an alternative candidate for a vertebrate ancestor, the researchers propose the armoured Devonian fish called ostracoderms, which look a lot like tadpoles going to war.

“Lampreys are not quite the swimming time capsules that we once thought they were,” said co-author Michael Coates, a biologist at the University of Chicago, in a Canadian Museum of Nature press release. “They remain important and essential for understanding the deep history of vertebrate diversity, but we also need to recognise that they, too, have evolved and specialised in their own right.”