A few weeks back, during a particularly unremarkable late night of insomnia-fuelled doomscrolling, a notification slid its way onto my phone’s screen that quickened my pulse and dilated my pupils. For the next few minutes or so — there was no way to be sure for how long — the long out-of-stock Pokémon cards that I, and other collectors around the world, had been hunting for were just a few taps away and available for free shipping.

At the time, I thought I’d struck gold, but as I attempted to check out, I ran into a soul-crushing roadblock. It was the same one many collectors have encountered in the months since Pokémon cards became hot-ticket, pandemic-era items ahead of the franchise’s ongoing 25th anniversary celebration. Though there’d been a box of cards in my online cart mere moments before, I wasn’t the only one eyeing them, and in my brief moment of hesitation, the pocketable monsters I’d found were apparently gone again. Try as I might, there was no way of denying the truth of the renewed “Out of Stock” button that was staring back at me.

[referenced id=”1226100″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2020/06/pokmon-sword-and-shields-new-isle-of-armour-expansion-is-a-breath-of-fresh-air/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/26/z1vnxebesqbhvtr5hvcv-300×168.gif” title=”Pokémon Sword and Shield’s New Isle of Armour Expansion Is a Breath of Fresh Air” excerpt=”When Nintendo first announced that game’s publisher would.”]

Over the course of the past few months, Pokémon cards and the community around them have gone through a peculiar evolution that’s been driven, in part, by people’s continued fascination with the idea of children making their magic pets fight, but also by how covid-19’s lockdown measures inspired many people to either pick up or get back into collecting habits. As anyone who lived through the ‘90s can attest, Pokémon card crazes are anything but new, but what’s happening in the collecting space right now feels distinct and like the convergence of multiple cultural phenomena that goes way beyond Pikachu and his buddies.

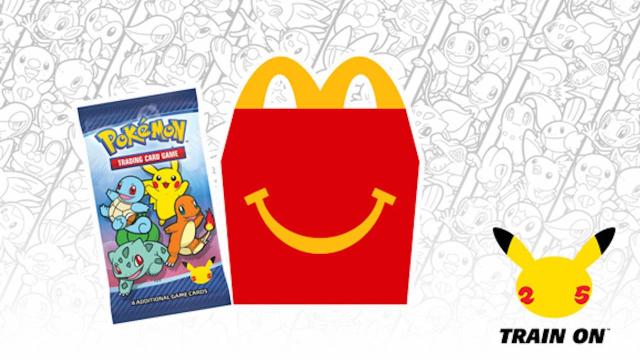

To celebrate Pokémon’s 25th anniversary, the Pokémon Company — the outfit consisting of developers Nintendo, Game Freak, and Creature who oversee the intellectual property — has been releasing special commemorative merchandise along with regular drops of new sets and cards every few months, as has been the case since the mid-‘90s. As one of the Pokémon Company’s longstanding promotional tie-in partners, it made sense when McDonald’s was announced as one of the first places fans would be able to snag some special merch. Specifically: packs of limited edition cards packaged with Happy Meals. What caught many people’s attention and made headlines about the McDonald’s promotion wasn’t the value or rarity of the cards themselves, but how difficult actually getting ones’ hands on them became.

Larger-than-expected crowds flocked to participating locations to buy the shiny pieces of cardboard up in masse. People turning up in droves to buy kids meals for the toys also isn’t a new thing, or unique to Pokémon cards — McDonald’s went through a similar situation back in the ‘90s when it was briefly in the business of selling Beanie Babies at the height of their popularity. But unlike the thousands of miniature Princess Diana-inspired bears that people hoarded for years in hopes that they would one day be valuable enough to flip for a massive profit, the 25th-anniversary Pokémon cards began to resurface in the wild rather quickly, albeit on eBay, where literal boxes of them were being sold for exorbitant prices. Aftermarket prices for the cards have leveled out considerably since they first started showing up in online shops, but the fact that entire cases of them went unopened before many people even had a chance to buy them using the regular route is illustrative of the issue at hand.

@McDonalds @Pokemon I sure hope you do some form of inventory control for your promo Pokémon cards as some of your stock is being sold in sealed boxes which means they’re not even making it to your stores ???? Though same thing happened with Tim Hortons Hockey too. Retail $1.99 ???? pic.twitter.com/kX8qZyRX2V

— redphoenixsportscards (@redphoenixcards) February 9, 2021

In a time when countless people became generally homebound in a way that pushed them to find new ways of entertaining themselves, it was easy to imagine that boredom and novelty alone were the underlying causes of McDonald’s across the United States being sold out entirely of the special cards just days after the Pokémon Company officially announced the promotion. To fully understand what was (and still is, for the most part) going on, you have to look a little further back to appreciate certain things about how the different communities that exist around Pokémon as a franchise have changed over time.

Even though the public’s initial bloodthirsty obsession with collecting Pokémon cards back in the day gradually mellowed as people traded in their Gameboys Colour for Gameboys Advanced and Nintendo’s subsequent handheld systems, the community of competitive Pokémon Trading Card Game (PTCG) players has been something of a constant for decades. While the Pokémon franchise has continued to expand far past cards, competitive leagues of card players have been a part of the fandom since the late ‘90s when people were first able to start their own local groups for enthusiasts styled after the leagues featured in Pokémon games.

Like the game leagues, trading card game leagues brought players together to battle and trade in friendly events (usually hosted in mall game shops) where participants could collect prizes and badges reflecting their battling skill. In addition to local Leagues, players have been able to participate in City, Regional, and World Championships, all of which have been overseen by Play! Pokémon, a subsidiary company created in 2003 to handle organised card events following Wizards of the Coast losing its Pokémon licence that same year. Even in times when Pokémon cards weren’t in the spotlight, the competitions (and sizable prizes that come along with winning them) were very much still a thing. They’ve continued to be, with annual tournaments for the game becoming increasingly high-profile events.

Because the competitive community around the Pokémon video games and card games are closely linked together, it makes a certain amount of sense when you consider how the collection of cards has become a large part of the present-day YouTube/Twitch streaming space. There are hundreds (if not more) content creators who’ve churned out thousands of hours of themselves tearing into individual packs and ripping into boxes full of Pokémon cards in a way that’s very much a part of the streaming age’s obsession with parasocial relationship-inducing unboxing videos.

Most everyone has a story about a “friend” they “know” who ended up selling their old Pokémon cards for a pretty penny (those words are in quotes because these stories always tend to have an urban mythic quality to them). But what’s become increasingly common in recent years are instances of people being in the news just for that and showing how, in some instances, holding onto rare cards can pay off both financially and in terms of a person’s notoriety.

Streaming is a part of what brought Yussef Abdala, a New York City-based Pokémon card collector and streamer, to a local Target where he and I met in line recently. Like almost everyone else waiting that day, Abdala had shown up hours earlier with a group of friends to put their names and phone numbers down on a list in order to be contacted after the store’s new stock of cards was dropped off that same day.

I happened upon the Target queue purely by chance and assumed there must have been some sort of announcement directing people to line up in front of the customer service counter, where a harried Target team member (their term for employees) stood guarding a small horde of assorted Pokémon products. Abdala explained, though, that the new queueing system had been put in place quite suddenly with no apparent warning.

“We learned about the queueing system because we literally come every week to buy to collect,” Abdala told me after taking a moment to step out of line to gauge how many people were ahead of us both. “I guess it makes it easier. If you’re in it to collect, if you’re just here to buy — like if I was a mum, I would prefer this, because it gives my son a shot, you know?”

In response to the current spike in Pokémon card sales and subsequent shortages in many locations, Target stores across the country began taking different measures like the queueing system in order to give more people the opportunity to buy the products in stores. Much of the current card drought for both regular products and promotional events like the McDonald’s tie-ins link back directly to the cards’ popularity online and the countless scalpers looking to capitalise on the moment.

There are obvious parallels between the Pokémon card shortage and the scarcity that drives much of the sneaker aftermarket that pops up in the wake of new releases of highly-anticipated shoes. From Abdala’s perspective, though, the dynamic with the cards is further complicated by how much more relatively accessible they are to scalpers, who are often also collectors themselves. At times, he explained, the online Pokémon card collecting community can feel like an ouroboros.

“Because the scalpers, they themselves go onto Twitch to see what everybody’s spending their money on, so then it becomes even harder for us to collect the merchandise,” he explained. “They kind of mess with the market with all of this buying and selling. It’s gotten to the point where people I know who collect Pokémon now collect sports cards. They’re opening up packs, not pronouncing people’s names correctly, don’t know what teams they’re on, and it’s like, ‘Oh, you’re not collecting this because you’re into it.’”

You don’t have to look hard to see how Pokémon card collecting for the express purpose of building one’s professional social media presence has become part of how some people engage with the franchise online. But what’s been interesting to see during the current covid-era shortage are the handful of communities that have popped up seeking to help normal people get their hands on the items, and how these communities feel like part of a larger, somewhat altruistic energy present in the Pokémon fandom.

Because there’s a pandemic still on and this is the 21st century, online shopping has been the other popular route people have taken in their hunt to buy cards on top of a variety of different retailers, like the Pokémon Centre, big-box stores, independent gaming shops, and open online markets. Throughout the shortage, it’s actually been quite easy to find packs and Elite Trainer Boxes from recently released sets, like the Galar Region-focused Vivid Voltage, shiny Pokémon-centric Shining Fates, and Battle Styles, the newest set that introduced The Isle of Armour’s bear Pokémon, Urshifu, on online open marketplaces.

The catch, though, is that most independent sellers are selling their stock of new sets at drastically inflated prices in response to the high demand. What many people, including myself, have been aiming for was just to buy some cards at the price they were meant to be sold, which has meant either choosing to rely on stores’ in-stock notifications (which seldom seem to work) or, in some cases, looking to places like the @CharmenderHelps Twitter account.

When I spoke to Daniel — a 29-year-old Florida man who runs the “CharmanderHelps” account when he isn’t running his own online retro gaming company — he had his own memories of journeying to Toys ‘R’ Us with his father on the weekends to participate in local Pokémon Leagues. While getting back into the Pokémon scene in 2020, Daniel could feel how much more effort it took to buy cards when, just months before, they were easy enough to come by just by walking into stores.

[referenced id=”1091198″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2018/03/annihilation-is-actually-a-warning-about-how-dangerous-the-world-of-pokmon-really-is/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/28/b4xpm6i8gr5wjconv7vt-300×169.jpg” title=”Annihilation Is Actually A Warning About How Dangerous The World Of Pokémon Really Is” excerpt=”To everyone marveling at how imaginative and wondrous all of Annihilation‘s fantastical, mutated creatures are, you realise they’re all just Pokémon, right? We’ll explain below – but it will involve a great number of spoilers for the film, so beware.”]

“One day I thought hey, maybe I can help and so I made a Twitter account,” he told me over Twitter DM. “I have over 10 years of experience deal-hunting so I thought I could put that into better use by helping others, and so here I am.”

CharmanderHelps lives up to its name in a rather straightforward way. As stock at various online stores Daniel monitors become available, a tweet with a link goes out from the account, and within seconds, dozens of followers swarm in the hopes of securing their grails. Though there are certain rules of thumb people have developed to expedite the checkout processes at places where roadblocks like PIN codes are common, the entire process is essentially a free-for-all in which one’s timing, speed, and attentiveness all play key factors.

If the entire idea of following a Twitter account in order to breathlessly buy Pokémon cards the minute you see them seems a bit exhausting, that’s because it is. But accounts like CharmanderHelps have become one of the few bulwarks against scalpers, who in some instances deploy bots in order to rapidly buy up large sums of online inventory at U.S. stores like Best Buy, Walmart, and Target. Chaotic as the process may seem from the outside, Daniel explained that because hunting for deals is something he was already familiar with, it isn’t actually where he focuses the bulk of his CharmanderHelps energies. More often than links to where to buy cards (again, there’s a shortage), CharmanderHelps is usually filled with retweets of people sharing details about where they’ve recently seen merchandise out in the wild. The idea is that they pay their good luck forward to people nearby who also follow the account.

It’s that energy, Daniel said, that some people new to Pokémon and who only just now started to pay attention to the collecting spree usually fail to see, particularly when they’re focused on making money. “I see comments often on my tweets asking ‘Is there a Charizard in the set?,’” Daniel said. “‘Is there something expensive?,’ ‘What booster packs do people want most?’ It’s pretty much a gamble to them. They’re not actually in it to collect and it seems like they think everyone else is there for the same reason.”

Annoying as the questions may be, there is a ‘Charizard-like’ card in almost every set — meaning the rare, coveted items that carry a disproportionate amount of value because they typically have legendary Pokémon featured on the box art — in reference to the ultra-rare, shiny Charizard from the TCG’s 1999 base set, which can fetch thousands of dollars on the aftermarket today. It can’t be ignored that CharmanderHelps is a hunting resource from which Daniel sometimes profits from himself as much as it is a place where fans interact. But Daniel’s followers do seem to have a rapport with one another. In truth, it can read a lot like the kind of camaraderie you often see develop between fans at in-person conventions that became impossible to attend last year.

Aside from the masks, social distancing, and distinct lack of people in costumes, the buzz running through that Target where I stood waiting for cards was indistinguishable from the slightly sheepish excitement you can feel radiating off people at any comic con. The uncertainty of whether fans would actually be able to get what they came for was an obvious point of stress, but mixed in with people’s slightly-too-loud proclamations of how unbothered they would be if they went home empty-handed was a resolute hope grounded in some basic logic.

Collecting Pokémon cards has always been a game of probability, but things like Target’s queuing system and knowing when the store was scheduled to receive new stock gave everyone waiting a solid idea of when and where to look. Beyond that, though, everyone waiting in line that day was well aware of the Pokémon Company’s recent move to ramp up production in order to specifically address shortage issues.

We’re aware that some fans are experiencing difficulties purchasing certain Pokémon TCG products due to very high demand. In response, we are reprinting impacted products at maximum capacity to ensure more fans can enjoy the Pokémon TCG.

More info here: https://t.co/sClZo3BXsp

— Play Pokémon (@playpokemon) February 10, 2021

Of course, being in line on that day meant not being patient enough for things to calm down, but that’s the nature of hype that you allow yourself to get into. Ultimately, the hype’s likely to die down, especially here in the U.S. as vaccinations continue to roll out and people are able to wander outside to do things that don’t involve buying collectibles in bulk. For the collectors who hopped onto this bubble because the whole point was to find enjoyment buying shiny pieces of paper, the inevitable bust is part of the fun, as is waiting out the scalpers.

Personally, getting back into another Pokémon craze similar to the original one that first pulled me into the fandom has been a fascinating, if at times frustrating, experience, because of what it’s highlighted about what happens when lifelong fans of a franchise grow up to become adults with some disposable cash on hand. In the Pokémon games, anime, and books, doggedly trying to hunt down Pokémon for one’s personal satisfaction is something that drives both the heroic protagonists and the villainous gangs like Team Rocket whose plans for global domination have only increased in scale over the years.

At times, hunting for and securing the cards in batches meant knowing that other people out there wouldn’t be so lucky in their searches, and in moments like that, the larger “game” could feel a bit Team Rocket-ish. But at the same time, competition, scarcity, and chance have always been core parts of the Pokémon experience, something Abdala reminded me about before we parted ways.

Regardless of how things feel as new drops are still being gobbled up by scalpers and bots at a rate that makes casual collecting more difficult, Abdala pointed out that eventually, things are almost certain to cool off and settle down, because that’s what always happens when hype and hustles intersect.

“There’s going to be more sellers than buyers and the market’s going to plunge at the end of the day because the people who are buying all these products, they’re going to hold on to it to try to make as much money as they can,” Abdala predicted. “But then they’re going to realise that the people who collect are not going to end up paying those prices. Then when they start bringing down their prices, there’s going to be that medium line where, ‘You know what? I’m just getting out of this.’ Like it’s not even worth it to wake up at two in the morning to make $20 at the end of the day.”