Film stocks from a century ago weren’t just limited to only capturing details in black and white; they could only capture a limited band of the colour spectrum, resulting in images of famous individuals that didn’t accurately represent how they actually looked. So a new approach to colourisation using AI finally takes that into account, resulting in eerily lifelike photos that look like they were snapped with a modern camera.

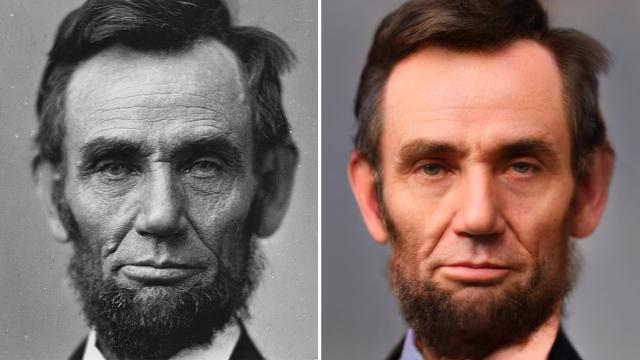

We’ve all seen old black and white photos of Abraham Lincoln that are dirty, noisy, and feature a shallow depth of field that only puts part of his portrait in focus. The low-quality images are the result of the limited capabilities of cameras and lenses at the time, but there was another problem at play that resulted in Lincoln looking more wrinkled with skin that appeared to be in desperate need of a moisturiser.

Before 1907, most black and white film stocks were orthochromatic, which meant that they were sensitive to all visible light except the part of the colour spectrum where warm tones like red exist. When light hits human skin, some of it bounces off, but some of it also penetrates the surface and illuminates the skin from within making natural features like wrinkles less obvious. It’s an effect known as sub-surface scattering and years ago finally understanding the effect helped revolutionise computer graphics and make virtual objects appear far more lifelike, but while it’s visible to the human eye, the effects of sub-surface scattering aren’t captured by orthochromatic film stock.

As a result, Lincoln always looked especially old in black and white photos, and traditional colourisation techniques don’t take what was really happening with old film stocks into account. Images are de-noised, enhanced, sharpened, and colour is applied in natural ways, but colourised photos don’t reintroduce the natural softening effects of light on skin that old black and white cameras simply couldn’t capture.

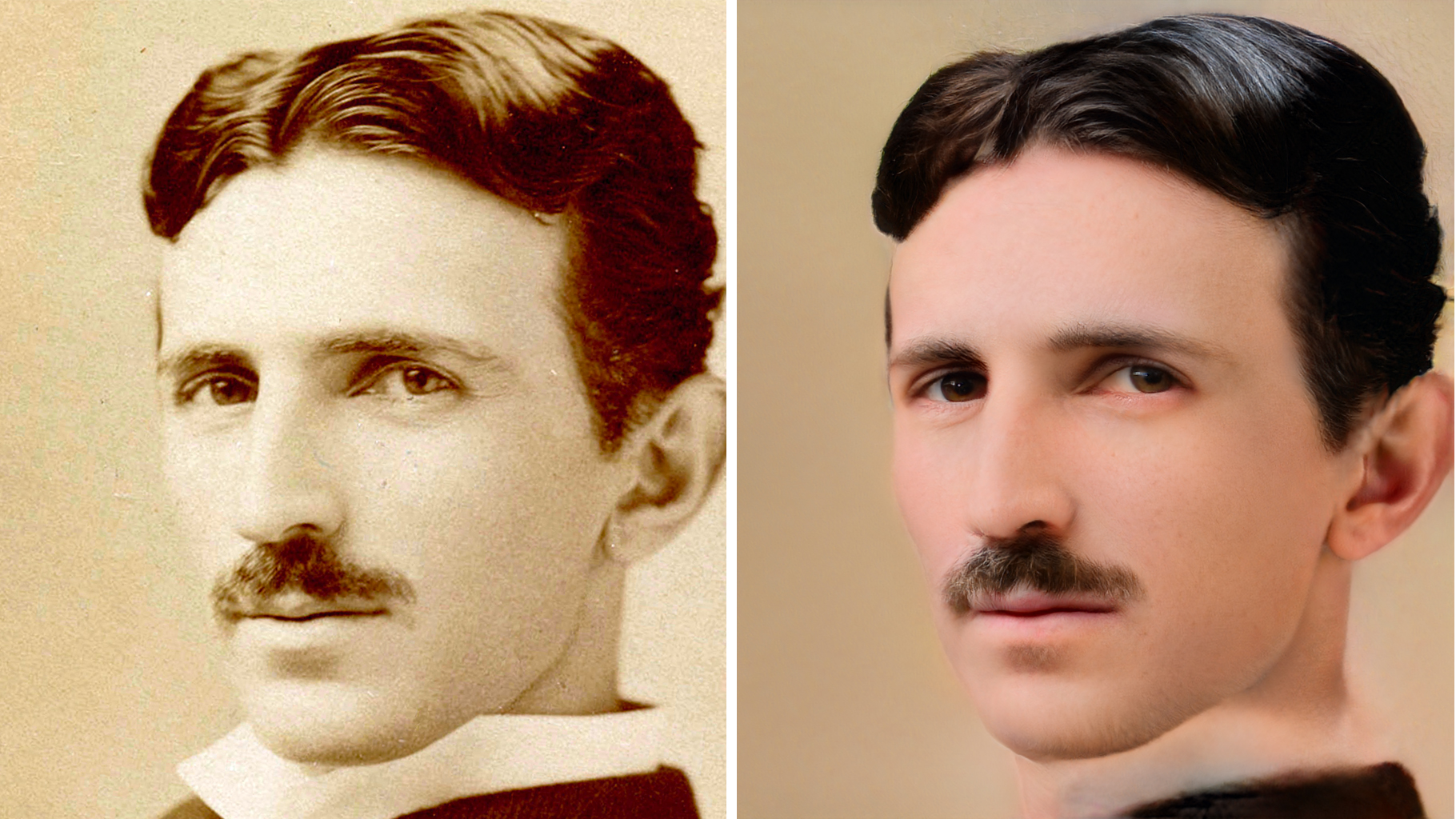

In just a few short years AI-powered image processing has come a long way, and a new colourisation technique called Time-Travel Rephotography is delivering impressive results by not just adding colour, but by also referencing photos captured by modern digital cameras to make corrections to the appearance of human skin. The new technique (detailed in a recently-published paper) was developed by a team of researchers from the University of Washington, UC Berkeley, and Google Research, and it starts by using an AI trained on a database of modern digital portraits to generate a sibling photo which shares a lot of the characteristics of the original black and white subject being colourised, but with a different identity.

The Time-Travel Rephotography process is also able to determine how the limitations of an antique camera degraded the resulting black and white image (including a lack of sharpness and contrast and exposure problems) and then correct those issues when the colourised styling of the generated modern sibling photo is applied to the original B&W portrait. The result is a new photo free of flaws that looks like it was snapped with a modern DSLR and a high-quality portrait lens, despite the subject having passed away a century ago.

The results of the new colourisation technique often appear incredibly lifelike, and it helps humanise people who’ve grown into mythical figures over the decades. But at the same time, it’s important to remember that colourising and modernising images is a process that introduces subtle changes and modifications to the originals — like the imperfections introduced when photocopying a document — and over time, as these modified images are released into the wilds of the internet and further processed (even image compression often negatively affects an image) these subtle changes will add up and in 10 years, the images of Lincoln circulating may look nothing like the wrinkled black and white portrait we started with.

[referenced id=”1240753″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2020/08/adobe-wants-to-make-photoshop-a-tool-for-spotting-fake-photos/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/14/tauqctbfplwwc1tz7pzw-300×169.jpg” title=”Adobe Wants to Make Photoshop a Tool For Spotting Fake Photos” excerpt=”For 30 years, savvy pixel-pushers have been using Photoshop to manipulate and edit imagery, but now that computers can create doctored photos all on their own using advanced AI, Adobe wants to leverage its image-editing tools to help verify the authenticity of photographs.”]

As AI image processing advances by leaps and bounds year after year, the need for a way to authenticate images, or properly label images that have been edited or enhanced, is becoming desperately needed. It’s part of the reason Adobe and other companies developed the Content Authenticity Initiative, a way to embed photos with a record of who and how they may have been manipulated over time, while others have pointed to the Blockchain as another approach to keeping track of an image’s authenticity.

[referenced id=”1675649″ url=”https://gizmodo.com.au/2021/02/deep-nostalgia-can-turn-old-photos-of-your-relatives-into-moving-videos/” thumb=”https://gizmodo.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/27/m6tbhmlecfbsf5ovycwk-300×169.gif” title=”‘Deep Nostalgia’ Can Turn Old Photos of Your Relatives Into Moving Videos” excerpt=”It’s hard to feel connected to someone who’s gone through a static photo. So a company called MyHeritage who provides automatic AI-powered photo enhancements is now offering a new service that can animate people in old photos creating a short video that looks like it was recorded while they posed…”]

Time-Travel Rephotography isn’t necessarily a bad thing: making historical figures who lived before motion pictures, TV, and sound recordings existed feel more real to later generations is a great use of the technology, and tools like MyHeritage’s DeepNostalgia have the potential to help people overcome grief or other unprocessed emotions related to the loss of a loved one. But tools like these do become an issue when artists have been accused of adding smiles while colouring photos of victims of the Khmer Rouge regime’s torture prisons in Cambodia, potentially minimising the gravity of these events for future generations who may not realise they’re looking at images that have been edited far beyond just adding colour.