The asteroid that killed off all non-avian dinosaurs made quite the splash when it hit the Yucatan Peninsula some 66 million years ago, generating a tsunami of epic proportions. Seafloor scars from this gigantic wave have been spotted in seismic data taken in Louisiana, offering new insights into this catastrophic event.

The megatsunami produced by the Chicxulub impact left a lasting mark on the seafloor, according to new research published in Earth and Planetary Science Letters and led by geophysicist Gary Kinsland from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. The analysis suggests the wave caused the formation of “megaripples” along the bottom. These megaripples are now buried deep underground, but their existence is further confirmation of the power unleashed by the asteroid on that fateful Late Cretaceous day.

That the 10 km-wide asteroid was able to carve the seafloor to such a degree is hardly a surprise. The kinetic energy generated by the impact was roughly 100 million megatons, which is akin to 10 billion Hiroshima-scale bombs going off at the same time. The collision triggered an impact winter that wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs and over 75% of all species on Earth. A simulation from 2018 found that the tsunami reached a maximum height of nearly 1,500 metres.

The Chicxulub impact occurred in the shallow waters of the Yucatan Peninsula in what is now Mexico, resulting in a global-scale megatsunami (North and South America weren’t connected yet, so this big splash was literally felt around the world). Empirical evidence of the megatsunami is sorely lacking, but research presented in 2019 suggests debris — and even fish — from the impact site were blown thousands of miles away onto what is now southwestern North Dakota. Accordingly, the new paper describing the megaripples deepens our understanding of this cataclysmic event and further proves that a gigantic tsunami was generated by the asteroid impact.

The seismic data used in the study was provided by Devon Energy. The Oklahoma-based energy company wasn’t looking for evidence of the Chicxulub tsunami but rather evidence of oil and gas in central Louisiana. Seismic images are acquired by sending shockwaves into the ground, and the resulting reflections provide a picture of sediments and other features deep beneath the surface. This part of Louisiana was submerged during the Late Cretaceous owing to higher sea levels at the time, so Kinsland thought it might be a good idea to see if evidence of the megatsunami appeared in the seismic data provided by Devon Energy.

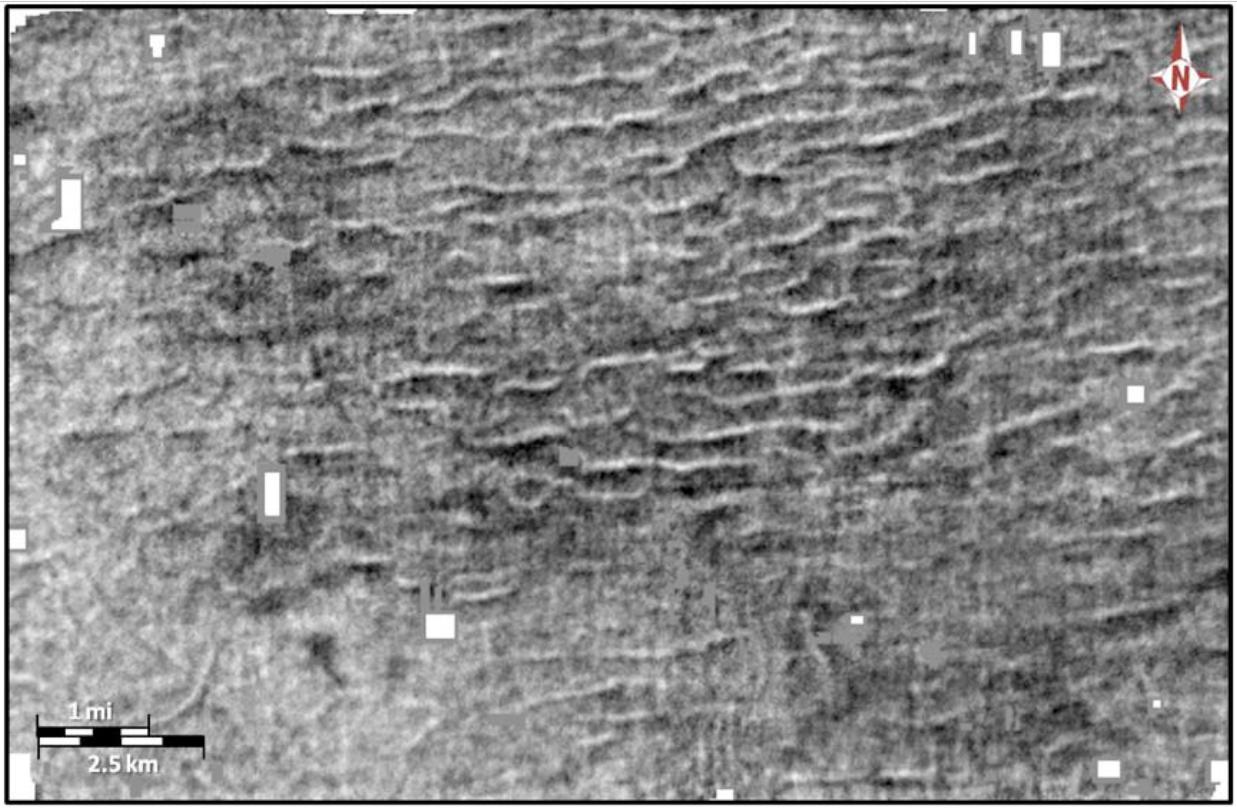

And indeed it was. The new paper documents a series of large-scale megaripples located nearly 1,500 metres beneath the surface. The studied layer dates back to the time of the impact, marking the “first time such buried, geologically old, tsunami megaripples have been imaged,” according to the study.

The ripples are separated by distances averaging nearly 600 metres and have an average height of 16 metres, “making them the largest ripples documented on Earth,” as the scientists write in their study. Kinsland and his colleagues say the orientation of the megaripples are consistent with having originated at the site of the asteroid impact. These features formed at depths reaching around 60 metres, as the gigantic waves from the tsunami surged northward.

“Since we see no evidence in the images of modification by marine or terrestrial erosion, we conclude that the megaripples were formed below [the] storm wave base on the [Yucatan] shelf and were buried and preserved by the Paleogene Midway Shale Group,” according to the researchers.

Ted Moore, a paleoceanographer and paleontologist at the University of Michigan, told Gizmodo that the new paper “beautifully illustrates” the power of the tsunami unleashed by the asteroid.

“Its stratigraphic position is spot on, and the fact that these ripples are preserved and not destroyed … by subsequent storms and tidal currents points to a wavelength that could only be associated with a tsunami — not a hurricane or other large storm,” Moore, who wasn’t involved in the new research, explained in an email.

Excitingly, this discovery means similar megaripples might be found elsewhere. Additional finds would further bolster our understanding of perhaps one of the most dramatic days in Earth’s history.