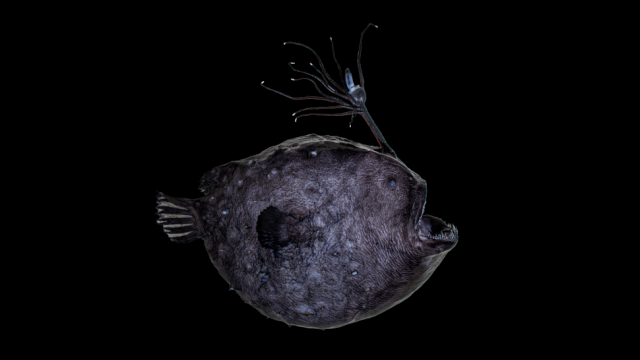

In May 2021, a Pacific footballfish washed ashore at Crystal Cove State Park in Newport Beach, California. Still in good condition, the rarely seen fish featured spikes along its body, sharp teeth, and a bioluminescent lure. But as scientists would go on to discover, it also had biofluorescent tissue, a characteristic never seen before in this kind of fish.

Holy crap is the deep sea ever filled with all sorts of weird stuff. That this Pacific footballfish (Himantolophus sagamius) — one of 177 known anglerfish species — uses a bioluminescent lure to catch prey makes complete sense, given the animal’s pitch-black environment. But biofluorescence on top of that? That’s odd, as this form of glow typically requires an external light source.

“Anglerfishes are known for their ability to produce light, for their bioluminescence,” William Ludt, assistant curator of ichthyology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, explained in an email. “It was very surprising to discover that their lures, which can already be very impressive, are even more complex than we thought, with fluorescent tissues as well.” Ludt authored the new paper with Todd Clardy, collections manager for ichthyology at NHM.

Biofluorescence and bioluminescence may sound similar, but they’re two different things. Bioluminescence describes light produced by living organisms, in this case bioluminescent bacteria located on the anglerfish lure. Biofluorescence, on the other hand, is when organisms absorb light from their surroundings and re-cast it in a colourful glow. This combination of biofluorescence and bioluminescence has never been seen before in anglerfish, but it does exist in some deep-sea fishes like jellyfish and siphonophores.

Biofluorescence is actually quite common, appearing in species of amphibians, reptiles, birds, tardigrades, flying squirrels, platypus, and springhares, in addition to some fish.

The ichthyologists spotted the biofluorescent tissue without having to employ sophisticated tools or techniques. For the new study, published in the Journal of Fish Biology, “all we used was a fluorescent blue light, which just looks like a fancy flashlight, and a filter for our camera — and safety glasses for our eyes!” Ludt told Gizmodo. “It just goes to show that sometimes you don’t need an entire lab of expensive equipment to make exciting discoveries.”

Ludt and Clardy speculate that the Pacific footballfish’s biofluorescence is being fuelled by its glowing lure, given the absence of any other light source in the deep ocean. This particular species lives at depths of 1,000 to 4,000 feet (305 to 1,220 meters). Swimming in darkness, anglerfish use the tips of their lures, known to scientists as “esca,” to attract small fish, squid, and other prey, which are easily gobbled when they come too close. Like moths to a flame, these prey animals can’t resist the light.

“It’s possible that the fluorescent patterns we observed on this fish give it a slight advantage compared to other species that might not fluoresce in addition to bioluminescence, and in a habitat where it is hard to find food, that could make all the difference,” said Ludt, adding that, from an evolutionary perspective, “I think this highlights the many fascinating ways that animals have adapted to live in the deep sea, which is a very inhospitable place.”

The examination of the female specimen also revealed sharp and very thin teeth, some of which point backward to prevent prey from escaping after being captured. These fish look scary, but as Ludt pointed out, they’re not something we need to worry about while swimming at the beach, given their deep-sea habitat. Looking ahead, the researchers hope to document as many fish as possible, “including some of these rarer deep-sea species that only come up to the surface from time to time,” as Ludt explained.

More: Scientists Want to Know Why This Adorable Rodent Can Glow in the Dark.