The Book of Boba Fett’s second episode, “The Tribes of Tatooine,” not only shows a new side to the iconic character, but allows for a fresh perspective on the Tusken Raiders. The nomadic people of Tatooine have always been heavily influenced by Indigenous cultures, but the latest Star Wars series is taking them beyond the stereotype and providing genuine representation.

With over four decades of Star Wars stories, which seemed content to let the Tuskens maintain the “savage” stereotypes, I never imagined it would be something I’d see happen. Let alone done so competently. Too often in franchises that have become so ingrained in pop-culture to the point of reaching modern mythical status, most things try to maintain the status quo. This is especially true of what amount to lore for background characters.

I want to make something clear before I go on. Even as I speak from the perspective of a Native American, it’s important to remember we are not monoliths. I don’t claim to speak for all tribes, nor even for the majority of my own tribe. So don’t take this as the “Definitive Native Opinion on Boba Fett.” Beyond that, it’s crucial to acknowledge the influences behind Tuskens are pulled from many Indigenous cultures across the globe. There’s Māori in there aplenty, stemming from actor Temuera Morrison’s own background, but also a host of MENA (Middle East and North Africa) and SWANA (Southwest Asia and North Africa) influence which shouldn’t be overlooked.

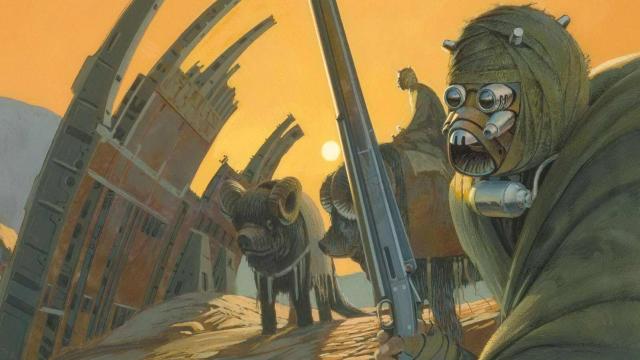

George Lucas himself said much of the Tusken look/design was based on the Bedouins, an Indigenous Arab tribe from the desert regions in South Africa. One of the driving ideas behind so many of the initial Star Wars designs stemmed from taking something recognisable, but altering it into something new. In A Gallery of Imagination: The Art of Ralph McQuarrie, Lucas explains, “You look at that painting of the Tusken Raiders and the banthas, and you say, ‘Oh yeah, Bedouins…’ Then you look at it some more and say, ‘Wait a minute, that’s not right. Those aren’t Bedouins, and what are those creatures back there?’”

I can’t speak to those aspects — nor would I try to declaratively, in case I seriously misrepresent something. So the majority of the perspective you’re going to see from me is directly connected to my Native heritage. This in no way means I’m forgetting about the others.

In the Beginning

From the outset, Star Wars pulled from Native American culture to integrate into its storytelling. It’s something I’ve talked about at length before. Tuskens are a major callback, of course, but throughout the decades many Native influences have found their way to the galaxy far, far away. During the mid-90s Tales of the Jedi run of comics, we could see the general Native influences on the overall character designs. After all, the idea of those comics was to show a more “primitive” side to the galaxy and Jedi order. Even the early origins of the tribal nature/clan structure of the Mandalorians has its roots in these comics, before being expanded upon in Knights of the Old Republic. Genndy Tartakovsky’s Clone Wars microseries in 2003 gave us the Nelvaanians; a race so based within Indigenous culture the women carried younglings in papoose carriers! In the story they’re introduced in, Anakin himself embarks on a vision quest of his own, guided by an elder shaman complete with hair wraps evocative of Native fashion.

The influences have been many over the years, but those interpretations weren’t always for the best. Such is the case with Tuskens. Star Wars is essentially a “Space Western” and the genre has long been a heavy influence on the franchise; taking on most of the familiar tropes in the process. Of the many films that helped influence the original Star Wars, John Ford’s The Searchers is one of the most recognisable. From the direct visual parallels of John Wayne’s Ethan returning to a burned out homestead, and even reaching into the prequel era with Attack of the Clones. Anakin’s mother Shmi is abducted by a band of vicious Tuskens, sending him on a mission to find her, a story echoing the Comanche abduction of Ethan’s niece in The Searchers.

Nothing is more synonymous with older Western stories than Native Americans being the antagonists. They’re the “savages” making trouble for the more “civilized” heroes looking to tame the wild countryside. In A New Hope (and the Prequels), nothing embodied this more than the Tusken Raiders. They fit the trope to the letter: from raids on the settlers, wantonly kidnapping people, and even animalistic behaviour. Over the years, however, many different creatives on the books and comics side of things have worked to alter how people view the Tuskens in general. John Jackson Miller’s novel Kenobi (now deemed non-canonical to current events) provided a more nuanced look into their culture, through the lens of Obi-Wan coming to a better understanding of them.

Well before that, however, the comics gave us Sharad Hett in the latter part of the ‘90s. Hett was a Jedi Knight who exiled himself to Tatooine and became a Tusken warlord. In the comics, his time with the Tuskens utilises a number of Native American tropes/historical elements to deepen their lore. Namely, it introduced the idea Tuskens would “adopt” orphans into their tribes — an idea we’d eventually see integrated into Mandalorian culture too, with the concept of “Foundlings,” kids who were made orphans thanks to the raids on settler camps and other conflicts. Historically speaking, Native American tribes would do the same with the surviving children from their own attacks. While the media presented this idea as something barbaric, Tribes normally did this as an act of mercy. Unlike those who came onto their land and drove them out, they saw killing kids — true innocents — as a horrendous practice. Nevertheless, Natives stealing children and indoctrinating them into the tribe made for a great plot device in Western stories. It’s a story point even recent films like Tom Hanks’ News of the World, takes advantage of.

But in these Star Wars comics, Hett meets, falls in love with, and marries another Tusken named K’Sheek. K’Sheek was one of these settler orphans adopted by the Tuskens, who eventually gave birth to A’Sharad Hett, another Jedi who went on to fight against the Yuuzhan Vong (later revealed to be the villainous Darth Krayt 100 years later, but that’s a whole other thing). With each story in what is now known as “Star Wars Legends” over the past couple decades, it’s been cool to see how these Native cultural elements have become crucial to the history associated with the Tuskens. Now, however, we’re finally seeing that play out on the screen. The Mandalorian helped pave the way in its first two seasons. Namely, we get to see them interact and engage with people beyond being “raiders.” Din Djarin actually holds conversations with the Tuskens, seeing them communicate on screen for the very first time thanks to a specially crafted form of American Sign Language (ASL). While it may seem minor, the simple act of giving Tuskens the ability, and time, to communicate with others, goes a long way towards humanising them in the eyes of viewers.

Furthermore, we got to see some of their personal struggles in the show’s second season. They too are struggling with the Krayt dragon, and know they aren’t able to defeat it on their own. Through the viewpoint of Cobb Vanth and other citizens of Mos Pelgo, the audience is similarly able to shift their perspective on Tuskens from brutal savages to regular sentient beings. As awesome as all that was, however, The Book of Boba Fett, blows the gates of representation wide open. Far beyond anything that’s come before.

Diversifying the Tuskens

I think the thing I’ve loved most about the Tuskens we’ve dealt with in Book of Boba Fett so far is how distinctly different they are from any other iteration of the people we’ve seen before. From the way they dress, even to the types of tents they utilise (triangular rather than rounded), it’s clear they aren’t the same kind of Tuskens any of our heroes — or villains — have dealt with. At one point, the Chieftain even makes mention of “other tribes” who resort to more aggressive tactics to survive. While they all share many of the same cultural aspects, they are also unique–just like the many Native American tribes, and other Indigenous communities around the world.

When you have a government in place who systematically wipe entire people off the face of the planet, it’s easy to lump all Natives into a singular category. It’s something movies, shows, and books have been doing for well over a century; perpetuating the idea that all of us are the same. The truth, as with any race, is significantly more complicated. While many tribes share familiar cultural aspects (similar food, shared mythologies, etc), each of them are undeniably different. Hell, even based on the history we have now, we know of at least 200 different languages, not including divergent dialects, utilised across the country! In many ways, the early history of the Americas isn’t too dissimilar to the European history we learn about in schools. With those, we’re taught the constant wars over various kingdoms and theologies were to be romanticized, the same kind of wars fought between tribes were considered barbaric. This mindset comes down to treating all Natives as a singular group rather than being from a diverse continent, full of unique peoples.

Even the earlier Expanded Universe attempts to flesh out the Tuskens generally resulted in them being treated as a homogeneous group. Regardless of the fact they were spread out over an entire planet, comics and books depicted all of them in almost the exact same clothing, sharing the same rituals (youths having to hunt Krayt Dragons to prove themselves), all while referring to them as a singular entity. In essence, one could encounter Tuskens on opposite ends of Tatooine and end up with the same experience. With The Book of Boba Fett, we get to see the diversity between the tribes. We see the Chieftain explain a bit about their own history (one I’m sure would diverge from other Tusken tribes out there), while exploring rituals we’ve never seen before. While they share many of the same core elements, there’s a sense they do things differently from other tribes.

It may seem like a small thing in the bigger story, but the result is opening up the Tuskens to a new world of nuance. Yes, some can be barbaric and dangerous (as the ones who captured Shmi Skywalker obviously were), but no longer are they indicative of the entire people. Our perspective has shifted, allowing for the acknowledgement of multiple unique peoples/cultures. This is something rarely seen even in modern movies and shows featuring actual Indigenous people.

Land Back

On top of expanding their overall presence, The Book of Boba Fett also provides the Tuskens with a more clearly defined existence beyond simply being brutal, underdeveloped, savages. As we learned in “The Tribes of Tatooine,” the Tuskens have existed on Tatooine all the way back to a time when water flowed freely on the planet. To them, everyone is an “offworlder,” which is a fairly typical colonial story. People come from elsewhere, encounter others they deem primitive, and proceed to claim everything for themselves in the name of civilisation. It might not sound bad on paper to these settlers, but the reality is a whole bunch of relocation and genocide. Any attempt at pushing back against this forced civilisation is seen as ungrateful and needlessly aggressive, and a justification needed to continue committing more atrocities.

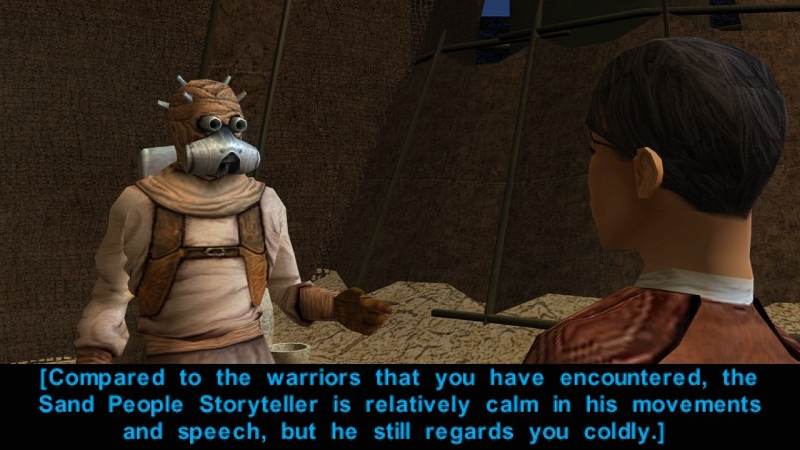

This is what the Tuskens have been dealing with for millennia now. In all that time, they are continually looked upon as the bad guys for it. It’s not a new concept for Star Wars. In fact, the first Knights of the Old Republic game dealt with this fairly deeply during your missions on Tatooine. There, you can explore a Tusken enclave — or slaughter them — and speak with their tribal Storyteller if you complete the right sidequests. Through this, you get a clear picture of their history, subjugation, and how it has all led to their current outlook. At the current point in time we see them in the films and The Book of Boba Fett, their desire isn’t about reclaiming ancestral lands, so much as it is not losing what they have left. The chances of Tuskens reclaiming Tatooine on the whole isn’t likely to happen, and they’re smart enough to know that. They merely want to maintain what they have and live out their lives without fear of being gunned down from crime syndicate hovertrains for no reason other than being close by.

In this regard, Book of Boba Fett isn’t necessarily doing anything new with the Tusken’s displacement story, but it absolutely puts it in the proper context. Through Boba’s eyes we see they aren’t mindless brutes, but a people with their own deep history and culture who want to protect it from outsiders who couldn’t care less. It’s obviously something Fett himself had never thought about. Considering his own background (losing his home as a child, and his connection to Mandalorian heritage through his father), there’s a clear parallel between them and a major reason he’s intent on helping the Tuskens in general. His time in captivity, and observing their culture, has taken him back to his own roots, giving him new purpose overall.

Showing Off

“The Tribes of Tatooine” hammers this aspect of Fett’s story home for audiences in a number of ways: being accepted into the tribe, crafting his own weapon, and even embarking on an old-fashioned vision quest! For me, however, the best scene came at the very end. Boba initiates a dance around the campfire, which eventually brings the tribe together in celebration. The biggest influence on this is clearly the Māori Haka. The ceremonial dance serves as a way to show off a warrior’s pride, strength, and overall unity with one another. Temuera Morrison has spoken about including his Māori heritage into his portrayal of Boba Fett even during his initial return in The Mandalorian.

“I come from the Maori nation of New Zealand, the Indigenous people — we’re the Down Under Polynesians — and I wanted to bring that kind of spirit and energy, which we call wairua,” Morrison said to the New York Times. Furthermore, he detailed how his prior training with the taiaha (a traditional Māori weapon) influenced Fett’s fighting style with the Tusken gaffi stick. It’s a point that feels more special now, having seen Boba Fett craft his own personal gaffi in a ritual granting him full acceptance into the tribe. Recently, in an interview with Yahoo Entertainment, Morrison explained how he felt a sense of responsibility to ensure his Māori heritage was treated correctly, “We know all about that word ‘colonised. It’s a great opportunity for me as a Māori from New Zealand to put us on the world stage again. I feel a sense of responsibility.”

During filming for the series, Morrison went so far as to, “Put the name of one of my ancestors on my chair, my changing room and on my parking space. So when I pulled in, there was my ancestor’s name: Tama-te-kapua, one of the captains that traversed the Pacific and arrived in [New Zealand]. It gave me a sense of pride … and a sense of responsibility for the people back home who will get to watch some of this stuff.” His heritage is a major part of his life and something he seeks to honour in all the work he does. As such it’s thrilling to see those Indigenous influences happen on the screen without feeling watered down, or changed to be more palatable for other audiences.

From my own perspective, the final scene in “Tribes of Tatooine” felt like watching a Native American Powwow in action. Indigenous cultures around the world share many similarities, so it’s not surprising to see that connection either. Regardless, I was floored watching it play out. Powwows are essentially big celebrations for the tribe, and have existed for as long as the people have. The modern version of the Powwow, however, came about in the 19th century, as forced relocations and genocide caused many tribes to come together and share in certain custom/rituals. During a majority of this time, the “Reservation Period,” most ceremonies and customs were outlawed. The only thing allowed, and only annually, were the dances because it was considered little more than a social gathering.

Thus, the Powwow turned into what it is today. Every tribe handles it their own way. As for my tribe, the Oklahoma Ponca, it’s essentially three days of partying. Families come together on the campgrounds, camping out and setting up pavilions filled with wonderful food and all manner of authentic crafts to buy. All of it is centered around the main dancing arena, a simple circle. At the centre sits the drummers and singers, with the dancers working their way around them in a circle as they play. The circular nature of the Tuskens dance (albeit around a campfire) immediately felt familiar to me.

I’ve danced at many a Powwow myself over the years and every time I have it’s a humbling experience. While there are competitions integrated into the Powwow, for the most part every song is open to the entire tribe to join. You don’t have to understand the song (performed in our language), or know the more complicated steps of the “grass” or “fancy” dances to participate. There are very basic steps that fit pretty much any song/beat. It’s meant to be an inclusive experience for all. Dancing in the Powwow links you to your fellow Tribesmen on a very foundational level. As you dance, there’s a sense of community, of being connected to something greater than yourself even if you don’t actually know the people you’re dancing with. Seeing it presented in the show, and done in a way that accurately captured that feeling, blew my mind. I was brought to tears and it’s something I haven’t stopped thinking about.

Flipping the Script

As I’ve mentioned, this is far from the first time Native cultural influences have been used in Star Wars. There’s a world of difference, however, between those elements being appropriative (presenting things in the negative or furthering stereotypes) and being representative. Prior Star Wars stories largely stuck to the stereotypes established by other media depictions of Indigenous people; mostly keeping them in the villainous role. Even the kidnapping of Shmi in Attack of the Clones makes little sense, aside from mindlessly torturing her for the hell of it. It all goes to serve the idea “Tuskens walk like men, but [are] vicious, mindless monsters” as Cliegg Lars puts it.

In the now-defunct Star Wars MMO, Galaxies, a story was integrated that gave birth to the term “Tusken Raiders.” Turns out there was a Fort Tusken on the sands of Tatooine, one of the very first settler compounds by those from other planets. As such, it came under constant attack — raids — by the Native tribes. It’s not hard to make a real-world historical connection there. Even later depictions, like the aforementioned Nelvaanians, did little to branch out from what most audiences expected to see out of Native cultures. While I think these were handled more tactfully, the fact remains, even the better examples continue to present the Indigenous cultures through the viewpoint of outsiders.

With The Book of Boba Fett, we’re finally seeing the Tuskens get a change in perspective on screen and the difference is night and day. Just take a gander at some of the online chatter from fans and you’ll see plenty of mentions about how people suddenly find themselves sympathetic to the Tuskens, where before they’d only looked at them as antagonistic. It’s a dramatic change. One that shows the power of what genuine representation can do. For those of us with Indigenous backgrounds the representation is special because it allows us to see our culture presented in one of our favourite franchises. For others, however, this type of direct representation goes a long way towards shifting the overall conversation.

Telling Our Own Stories

It’s not the be all, end all of representation, but The Book of Boba Fett Chapter Two provided the single most genuine look at Indigenous cultures in a galaxy far, far away to date. In one short episode, it managed to change the perspective on a significant group within that universe and I can’t begin to explain how thrilled I was to see it. It’s all the more frustrating to then see what the storytellers decided to do in the show’s third episode, “The Streets of Mos Espa.” With their narrative purpose seemingly served, the decision to kill off Boba’s Tusken friends is a bummer. It fully leans into the stereotypical tropes the previous episodes were intent on eschewing.

Narratively, it makes little sense as Boba already has renewed purpose and already been through the “trauma of losing family/home” story. In terms of representation, it felt like having the rug pulled out from under me, even though I wasn’t entirely surprised at the choice. While it doesn’t take away from the amazing things “The Tribes of Tatooine” gave us, it nevertheless comes across as a step backwards. If anything, it makes it more clear than ever that representation on the screen also needs to be backed up by rep behind the screen as well. I imagine a storyteller coming from an Indigenous background, who’s seen more than enough tribal destruction on screen for a lifetime, could come up with story options beyond killing off the Tusken tribe which would make more sense.

Star Wars has made strides on the book side of things, with Rebecca Roanhorse penning 2019’s Resistance Reborn; a tie-in to The Rise of Skywalker. Her incorporation of the Pueblo into the novel was exciting to see, but we haven’t seen that extend into any of the stories being told on the screen. Aside from Morrison bringing his own expertise to bear on the show, there’s no one else in the writer’s room lending their voice/experience to the story. Don’t get me wrong, I’m incredibly thankful for the things Book of Boba Fett have done in terms of Native, and Indigenous, representation. My frustrations don’t detract from the way my heart swells at seeing the haka performed in Chapter Two. It’s a significant step in the right direction, for sure. That said, there’s still plenty of discussion to be had about cultures in Star Wars going forward.