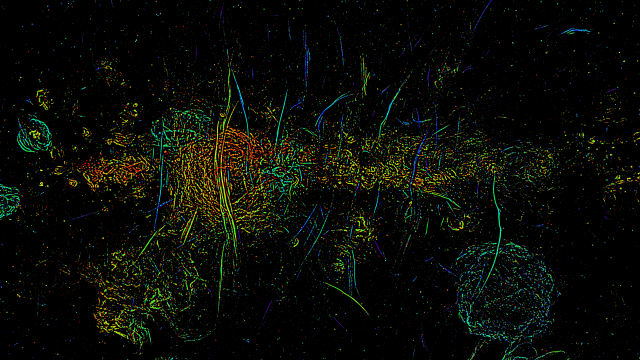

A new mosaic image taken by the MeerKAT radio telescope in South Africa has revealed nearly 1,000 multi-light-year-long electron strands at the centre of the Milky Way. The strands are huge streaks of cosmic ray particles; though they were discovered nearly 40 years ago, researchers never knew there were so many.

The MeerKAT array is just part of the massive Square Kilometre Array, which studies galactic evolution and cosmic magnetism, among other things. The recent image — comprising 20 separate observations in the radio wavelengths and totaling 144 hours — revealed 10 times more filaments than had been known previously. The team’s research is currently hosted on the preprint server arXiv and has been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“We have studied individual filaments for a long time with a myopic view,” said Farhad Yusuf-Zadeh, an astrophysicist at Northwestern University and the paper’s lead author, in a university release. “Now, we finally see the big picture — a panoramic view filled with an abundance of filaments.”

Armed with the new image of the strands, a group of astrophysicists recently conducted population studies of the huge one-dimensional structures, which stretch up to 150 light-years long and are composed of electrons that are interacting with a magnetic field. The structures appear in pairs or in small groups, making them look like massive scratch marks stretched across the centre of the galaxy.

The origin of the filaments remains unknown, but seeing a bunch of the structures at once has helped the team narrow down their list of suspects. Variations in the radiation emitted by the filaments have led the team to conclude that the strands are likely related to outbursts from the supermassive black hole at the Milky Way’s centre, Sagittarius A*, rather than the product of supernovae, or the explosive deaths of stars.

Yusuf-Zadeh told Gizmodo in an email that activity from Sagittarius A* could have shaped the cosmic rays into magnetized tails. The situation could be “similar to cometary tails when solar winds interact with a comet or a planet,” he said.

Going forward, the team plans to expand the region they observe, in hopes of finding more information about the filaments and their origin. In concert with imagery from other observatories, like the upcoming Rubin Observatory in Chile, the findings could help explain what sort of antics cause these phenomena at the heart of galaxies.

More: The World’s Largest Digital Camera Is Almost Ready to Look Back in Time