Archaeological evidence from the ancient city of Çatalhöyük reveals a complex funerary ritual in which human bones were dug up, circulated among the community, painted, and reburied. The colouring on exhumed bones has also been matched to paintings found on building walls.

The discoveries, which were recently published in the journal Scientific Reports, offer fresh insights into the burial practices of Neolithic Anatolians, specifically the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük (pronounced cha-tal-hoo-yook), an important archaeological site in what is now south-central Turkey.

Çatalhöyük is often referred to as the “oldest city in the world,” as it hosted upwards of 8,000 people at its peak. Inhabited from 7100 to 5950 BCE, the Stone Age city was home to many modern problems such as overcrowding, interpersonal violence, the spread of infectious diseases and rampant tooth decay, sanitation issues, and environmental degradation. Çatalhöyük’s inhabitants lived in mudbrick houses, fashioned clothing from trees, wore human teeth as jewellery, and manufactured baskets, ropes, and mats.

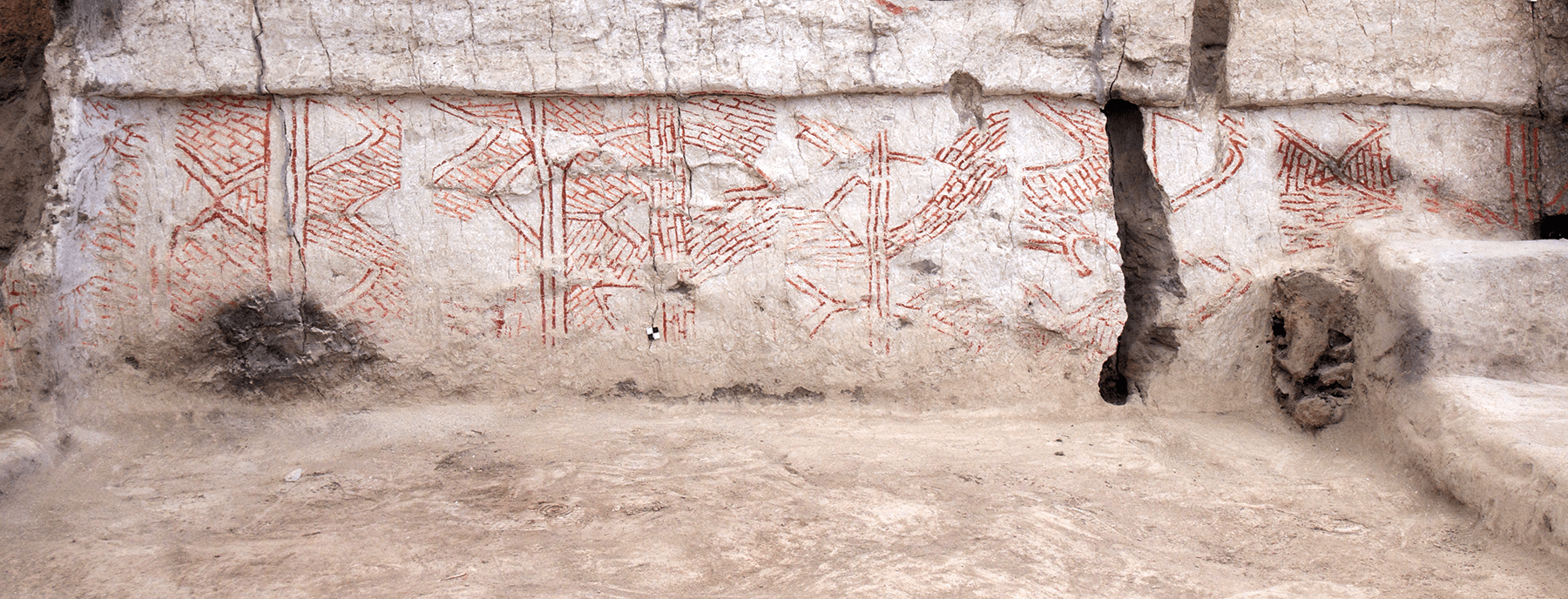

Residents of the city also used colourful pigments for both decoration and burials, and often both inside the same structure. “These types of findings have been usually studied separately,” said study co-author Marco Milella, a research fellow in the Department of Physical Anthropology, Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Bern, in an email. “However, we were intrigued by their possible association.”

Milella and his colleagues sought to discover which pigments were used at the site, the ways in which they were applied, and the relationship, if any, between the presence of colours on wall decorations and in burials.

The cultural use of pigments dates back tens of thousands of years, and possibly hundreds of thousands of years. In the Middle East, the use of pigments in funerary practices dates to the 9th and 8th millennium BCE. As the authors of the new study point out, prior examinations of these practices were focused on the bones and ritualistic oddities such as the removal of skull prior to reburial, at the expense of linking these practices to context such as artworks and architecture. The new research sought to overcome these potential oversights.

The researchers were not disappointed, finding some variability in the type of pigments used. Red ochre was the most common colorant, and it was found on the bones of adults (both sexes) and also on children. Bright red cinnabar was mainly found in association with males, while blue/green pigment was found in relation to females. These pigments were “either applied directly to the deceased or included in the grave as a burial association,” Milella said.

The archaeologists also found that the number of burials in a building matched the number of layers of paintings on the building’s walls. “Walls in a house were painted when a burial was performed in the same building,” Milella explained, pointing to a connection between the burial of an individual and the application of colours to that space.

The people of Çatalhöyük also participated in secondary funerary rituals, in which the bones and skulls of the deceased were excavated and circulated among the community. These skeletal remains remained in circulation for quite some time before being buried again, and secondary burials were also associated with wall paintings, according to the study.

Milella said the most fascinating aspect of the study is the questions it raises but does not answer. It’s not clear as to why some individuals were coloured with pigments and others not, or why only certain individuals had their remains dug up and circulated in the community. The observed selection of painted bones doesn’t seem to be related to age or sex; the selection criteria, if any, remains a mystery.

Ultimately, the new research “helps us to better understand the symbolic world of this Neolithic society, and about the relationship between the living and the dead,” Milella said. These visual expressions and rituals “were integrated parts of a shared sociocultural practice.”