A paramount rule of the animal kingdom is not to be seen unless you want to be. It goes for predators as much as prey: going unnoticed means surviving longer, either because it allows you to catch food or keeps you from becoming it. Here are some of the more creative ways that natural selection has produced effective camouflage in animals.

Exploiting Colorblindness

Ah, yes. The massive animal that somehow camouflages despite being bright orange. But as researchers described in 2019, tigers capitalise on the number of colour receptors used by their most common prey. Many ungulates (hoofed animals like deer and boar) are red-green colourblind, which means that the tiger’s striped body blends right into the greenery of the forest undergrowth. Mammalian hair is pretty much limited to browns, blacks, and shades of red and yellow, so the tiger’s luscious coat is the best way to appear lacklustre in its preys’ eyes. But now I wish that lime-green tigers existed.

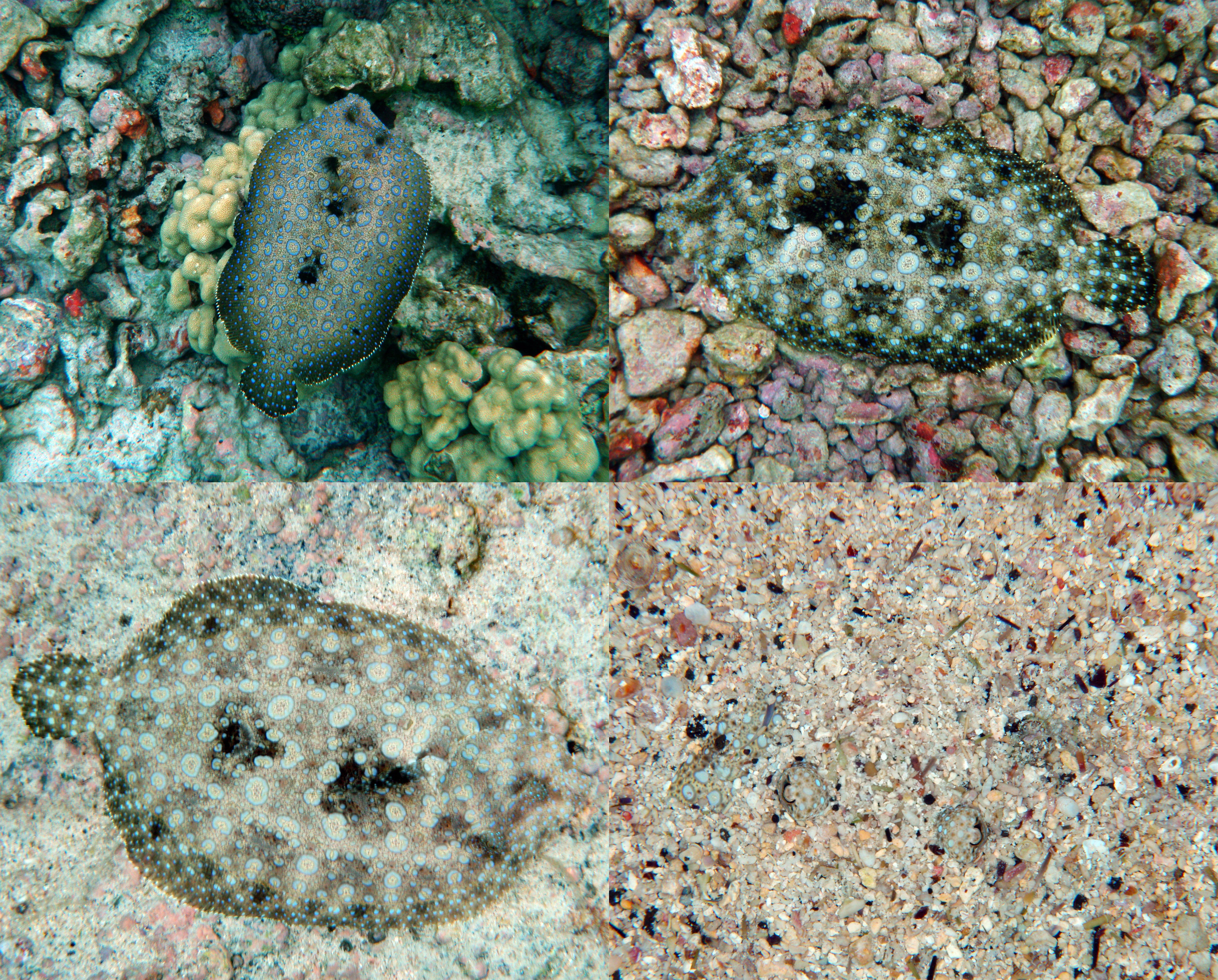

Spot the Flounder

This moldy pancake is actually the flowery flounder (Bothus mancus), a vivid plane of a fish that expertly changes its colour to match its surroundings. The very flat fish’s dorsal (top) side is covered in blue-ringed splotches, which help the animal blend in with the Indo-Pacific reef systems it inhabits. Many other flounder species also can change their spots — one 2017 study on flounder camouflage found that the animals matched most surroundings “in luminance and colour” and “matched the spatial scale of all substrates except for rocks.” The animals can also bury themselves in the sand — that’s where their flatness helps out — concealing themselves on the seafloor.

That’s Not a Leaf

Thank the deity of your choice for the genus Phasmatodea. That’s the entire group we collectively call stick insects, invertebrates that mimic the limbs and leaves of trees. For the most part, they’re very long and slender (hence the whole “stick” thing). The largest stick insect is also the largest insect in the world, at over 0.61 m long. The animals are typically the mottled browns or vivid greens you expect in a forest setting; though massive, you could walk right by one thinking it was flora, not fauna.

The Power of Countershading

Many animals are countershaded, meaning that their dorsal sides are darker than their ventral sides. The colour pattern occurs in animals terrestrial and aquatic alike and is one of the most common camouflage patterns in the animal kingdom (it was even present in dinosaurs). In the case of rock-hopping ibexes, countershading allows the tawny creatures to blend in with the rusty mountain slopes they inhabit.

Great white sharks evolved the same strategy. Viewed from above, they blend in with the dark depths of the ocean; from below, their light undersides blend in with the sunlight shining through the water’s surface.

Octopus Says Do Not Touch

Octopuses conceal themselves in their surroundings using chromatophores — cells that can change pigment dynamically — to match the colours of the seafloor, reef systems, and even other animals. But they also change the size and shape of projections on their skin, allowing them to replicate textures and look just as much like the ocean’s sandy bottom as bumpy corals. If all else fails, the animals can disappear in an inky smokescreen they expel from the same hole used for propulsion, respiration, and excretion.

Seahorses Just Doing Their Thing

Equine in shape but taxonomically piscine, seahorses defy your every expectation. The males bear children, and their broader family (which includes pipehorses and seadragons) are the only known fish with prehensile tails. But they also have tremendous camouflaging capabilities, which allow them to blend into whatever they’re clinging onto with their tails. Vibrant pink seahorses cling onto coral, and leafy seadragons grasp undersea vegetation. Even in an aquarium, you could miss them.

Ghosts in the Ocean

These crustaceans conceal themselves by becoming as transparent as possible. Cystisoma is an amphipod that is practically see-through at depths of 91.44 m to 1,000 feet, where sunlight can still permeate through the water column. At deeper, darker reaches of the ocean, the animals tend to be red or black, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Researchers recently studied Cystisoma up close and discovered structures that looked like bacteria on the animal’s shell, which reduced the reflection of light, making the animal even more transparent. If you can’t blend in with your environment, why not just vanish?