The first time that Patrick Comer tweeted about tabletop roleplaying games was in October 2021. He asked, “Who are hands down the best DND character illustrators out there?” He got one response.

That same month, an unassuming Twitter account was created: @gripnr. Its bio describes Gripnr as “a Web3 company building 5e TTRPG on-chain.”

If this has you confused, you’re not alone.

Gripnr is a company currently being built by Revelry, a New Orleans-based startup studio. Brent McCrossen, a managing director at Revelry, is the CEO of Gripnr; Patrick Comer is the president and head of product. That product, which nobody outside of the company has seen yet, is a digital platform meant to allow fans of the tabletop role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons to roleplay using NFTs indicative of Player Characters (NFT-PCs), and then save the details of their gameplay adventures on the blockchain, increasing the complexity and value of the NFT. They call this a “play-to-progress” system.

If you’re still baffled? Join the club.

“This isn’t adding anything to the gameplay experience,” says James Introcaso, an award-winning game designer who has worked on official D&D products. “A blockchain isn’t a game mechanic or campaign setting that encourages a player to engage with the game in a particular way.”

D&D writer and podcaster Teos Abadia is more critical of the idea. “Gripnr suggests a horrible self-centered and self-enriching concept that is anathema to the group collaboration and sense of mutual giving that makes the RPG hobby so special,” he says.

What is Gripnr and how is it (supposed to) work?

Gripnr, a reference to the mythological gleipnir chain in Norse stories, is a Web3 tabletop role-playing game (TTRPG) project currently in development, led by Comer, four handpicked tech supporters, and one tabletop RPG writer.

Right now the company is in the process of preparing its game content, mainly written by Gripnr’s lead game designer Stephen Radney-McFarland, a TTRPG veteran who has written for D&D and Paizo’s Pathfinder. His work will include lore and maps of a fantasy world currently called “The Glimmering.”

After this is complete, Gripnr plans to generate 10,000 random D&D player characters (PCs), assign a “rarity” to certain aspects of each (such as ancestry and class), and mint them as non-fungible tokens, or NFTs. Each NFT will include character stats and a randomly-generated portrait of the PC designed in a process overseen by Gripnr’s lead artist Justin Kamerer. Additional NFTs will be minted to represent weapons and equipment.

Next, Gripnr will build a system for recording game progress on the Polygon blockchain. Players will log into the system and will play an adventure under the supervision of a Gripnr-certified Game Master. After each game session is over, the outcome will be logged on-chain, putting data back onto each NFT via a new contract protocol that allows a single NFT to become a long record of the character’s progression. Gripnr will distribute the cryptocurrency OPAL to GMs and players as in-game capital. Any loot, weapons, or items garnered in-game will be minted as new sellable NFTs on OpenSea, a popular NFT-marketplace.

As PCs gain levels in-game, Gripnr asserts that their associated NFTs will become more valuable, and when they are re-sold, the owner and any creatives who contributed to the associated portrait will receive a cut of the sale price. Comer says this could mean as many as ten people could conceivably receive money from each sale, but could not provide percentages that each creative might receive.

Unfortunately, writing data to a blockchain isn’t as simple as writing hit points in pencil on a well-worn paper character sheet. Every time a user wants to perform a function on the Polygon blockchain — like adjusting the character level on a NFT-PC — they have to pay a gas fee, a tiny charge that helps fund the computational resources required to make the change. This means on the Gripnr protocol, there will be two gas fees per game that players must pay. Gripnr says it will keep fees down by operating on Polygon rather than another, more popular blockchain server system, like Ethereum (more on this later).

So in order to play on the Gripnr protocol, players will not only have to purchase a Gripnr NFT-PC, but they’ll have to buy (or earn) OPAL to pay for a game session or make purchases of digital goods such as items and adventures. Those purchases will help keep the tech company running.

To sum up: Players will buy a pre-generated D&D character, play with it in pre-generated adventures, level it up on the blockchain, and then sell it. It sounds like easy money, right? You’ll get paid to play your favourite game.

Unless you live in the real world, and not in The Glimmering.

Why Gripnr (probably) won’t work.

In an interview with Gizmodo, Comer emphasised Gripnr’s potential to distribute capital value to everyone at the table and behind the scenes. This is, according to Comer, one of its “core purposes.” But their plan to make Gripnr, and its NFT-PCs, valuable beyond a limited-edition release is riddled with vulnerabilities and relies on an as-yet barely real Gripnr community.

The biggest problem here is that Gripnr is basically making character sheets and recording the difference between the start and end of a session. There is no reason to use the Gripnr protocol except a desire to increase the value of your investment, which means that players won’t be playing Dungeons & Dragons for fun, they’ll be playing Gripnr to earn real-world money. Gripnr is creating a system of monetarily-incentivized gameplay that will require both GMs and players to invest both time and crypto-capital in NFT-PCs, on speculation that any single player’s NFT-PC will appreciate with gameplay and over time.

Gripnr says it can build out its Dungeons & Dragons-based NFT scheme under the Open-Gaming Licence (OGL). The OGL is a set of conditions granted by D&D’s publisher, Hasbro-owned Wizards of the Coast, in order to encourage independent game developers to design and sell their own content using the fifth edition rules for Dungeons & Dragons. But the OGL only allows certain elements and mechanics of the D&D system, not the whole game, and Gripnr has stated that it will “provide better options for 5e play” which players have been “clamoring” for. Gripnr doesn’t state what these options are, or what they plan to add to make 5e “better.”

“We do not allow third parties to misappropriate our valuable intellectual property and take appropriate steps when necessary,” a spokesperson for Wizards of the Coast told Gizmodo in an email.

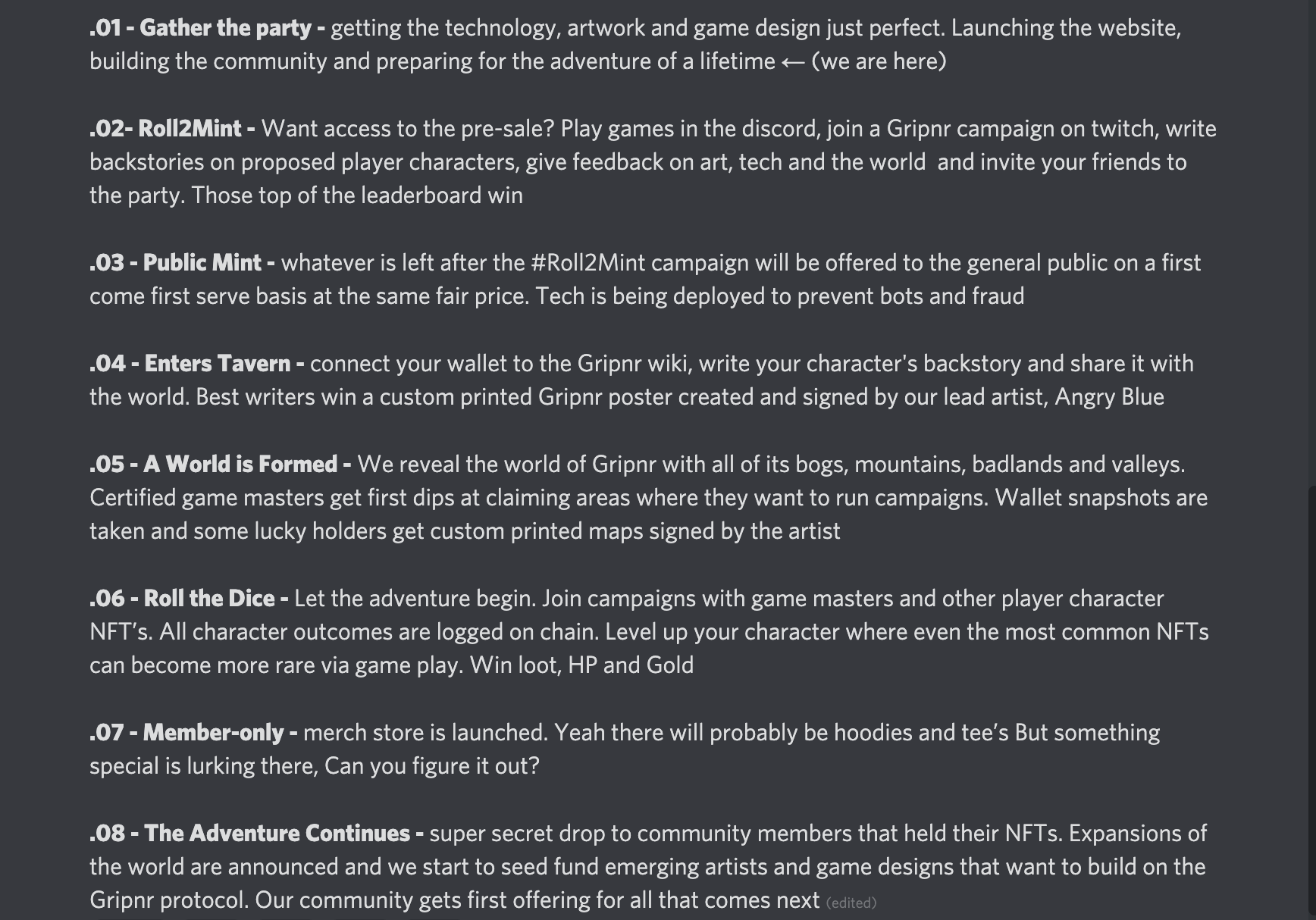

While there’s not much information on the specifics of what Gripnr is building, the company does offer a loose, phase-based roadmap on their Discord server, which was also publicly published at the bottom of The Glimmering’s information page:

Gripnr plans to reveal their protocol at the end of 2022, during Phase 5 of its development, but that is after it plans to mint 10,000 NFTs and release them this spring in both an exclusive presale (Phase 2) and a public reveal (Phase 3). Gripnr will not actually launch its play platform until Phase 6, which means that investors may have to stick around for months before their investment can appreciate through gameplay.

This means that individual community investors will be asked to put quite a bit of money in the Gripnr treasury long before Gripnr intends to deliver on-chain gameplay. It is this promised protocol that is the centre of Gripnr’s mission, and without it, all you’ve got is a pre-generated D&D character. Or a D&D character’s sword. The initial investment is so far ahead of the promised deliverable, it’s not hard to imagine the community might never see it at all.

Lars Doucet, a game developer who specialises in analysing blockchain-based games, told Gizmodo that “blockchain games always want to be user-generated content games, whether they recognise it or not.” But the user-generated value of D&D is in playing the game itself, in having an adventure with your friends, rather than the expectation of capital gain. This is what Gripnr is really competing against, Doucet says: The ability to play D&D on any other platform, including at the kitchen table. And Gripnr is giving players a lot of time to get bored with just owning an NFT when there are virtual tabletop services like Roll20 and Astral available for play right now.

The problem that Doucet sees with many of these blockchain-based games is that they are “play to earn” models rather than a “play and earn” model. With play to earn, you are playing with the primary objective of getting an item of value (in this case NFTs), instead of for the pleasure of playing itself, and receiving items as a bonus for your time. Because Gripnr is leading its mission with the goal of an increased payout versus the initial buy-in, they are ultimately “digging the hole and filling it back in again,” he says. The model is Gripnr-first rather than gaming-first.

Another major issue that Gripnr is facing is how to prevent fraud. In a scenario where a D&D character’s successes increase its real-world monetary value, there’s incentive for players and game masters to abuse gameplay — or even just fake a game, inputting values onto the NFT without actually playing — in order to artificially inflate the value of their NFT-PCs.

Comer is aware of the issue, and apologetic. He doesn’t quite know how to prevent fraud yet, he says, but he has a lot of ideas that are currently “being playtested.”

Andreas Walters, an IT systems analyst and an award-winning tabletop game designer, told Gizmodo that “despite using a ‘trustless blockchain’ to record events and make payouts, this all relies on both inputs and outputs from human actors, and with money involved (if any money is even being made), you create a system waiting to be exploited.”

This is especially true for Gripnr, which will rely on character sheet inputs from the GM, without any automation or virtual tabletop software to confirm basic data points like dice rolls. One solution proposed by Gripnr is to establish a system of checks and balances, at the centre of which are Gripnr-certified GMs, who will record their games using a third-party system like Twitch or Zoom, allowing other Gripnr GMs to review and audit the proceedings. But the system is still under development, according to Comer.

Another method Gripnr says it could use to prevent fraud will be to have every game’s GM offer one of their own NFTs as collateral, held by the company until a positive review of the game has occurred. If the GM is ruled to have cheated, the staked token will be “burnt,” or removed from blockchain circulation.

Even if all this cheating stuff gets ironed out, Gripnr will still have to deal with the inherent speculative nature of the NFT marketplace. The company–like other NFT startups — claims that NFTs help artists make “real money” for their work. But in the few cases where that is actually true, most artists have made money running their own minting process, not using a third-party company, and certainly not when that company stitched together random pieces of art to create 10,000 “unique” NFTs in a randomly generative minting process.

Teos Abadia sees this overwhelmingly massive minting as another problem for artists, not a solution. Companies “trading NFTs always claim to be for fair payment,” he says, “but my artist friends are all suffering because their artwork is being stolen by NFT companies. If we want character or magic item art, we can commission an artist and the money will go directly to the artist, without a Gripnr intermediary taking a cut. Gaming groups already commission artists to create custom art of their party.”

Like most claims about income within the NFT market, the value of Gripnr’s tokens is completely speculative. Those 10,000 NFTs will be worthless unless they are bought and sold by people who think they are an investment whose value–and not just its in-game complexity–will appreciate over time.

Those people may not exist. Right now, Gripnr’s community is tiny; as of Wednesday, April 6, the company’s Twitter account has less than 500 followers, and their Discord has half that. With such a massive drop of NFTs planned, who’s buying? And where will new buyers come from?

Comer admits there are likely to be many people who buy Gripnr NFTs because they’re collectors, rather than players, and promises there will be a “ratio” to balance out these different buyers. But if Gripnr is focused on building a community, anonymous rarity snipers are hardly going to make people feel like part of a group of tight-knit gamers. And it’s these core players who Gripnr needs to keep happy, or else they won’t have anyone to play on their protocol, and there will be no way for any NFT-PC to earn value, rather than to accrue speculative value.

On the Discord, one user said, “in some ways… community is capital.” Gripnr means it literally.

Crypto is meant to decentralize power, but Gripnr is planning to centralize within its own protocols. It needs to have players on its platform in order to create value via on-chain gameplay. It will release Gripnr-exclusive adventures, there will be Gripnr-approved Dungeon Masters, and the value of the NFT-PCs will only exist because of its technology. The value of Gripnr depends on centralization, undermining the mission of the Web3 technology it seeks to bring to the TTRPG space.

Besides, D&D is supposed to be about saving the world, not destroying it. Energy-intensive blockchain servers have been linked to increases in carbon dioxide pollution and electronic waste; crypto, as a whole, is a big-and-growing contributor to global climate change.

In his defence, Comer claimed on Twitter that the Polygon blockchain “uses 99.5% less energy compared to others.” But economist and writer Alex de Vries did an investigation into Polygon’s energy usage, and found that 99.5% figure “only measures the impact on servers Polygon owns, so it’s meaningless as a measure of impact, as Polygon actually runs part of its protocols on the Ethereum blockchain.” De Vries told Gizmodo he “conservatively” estimated Polygon’s carbon footprint through Etherium’s network, on February 3 alone, at 1,598,215 kilograms, or about 1875 tons per day. According to the University of Michigan, the average American home accrues 48 tons of emissions per year. In de Vries’ words, “this cannot simply be ignored.”

And Gripnr is not a “mint once” project. All adventure and gameplay outcomes put data back on the chain, which uses more energy. The company also plans to mint more NFT-PCs after over time; it could double or even triple those 10,000 NFTs over the next few years.

“At a time when we should be focused globally on reducing emissions, NFTs and blockchain are deeply problematic,” says Abadia, who works by day as an environmental health and safety consultant. “D&D is amazing with a pencil and paper. We don’t need to harm the planet to play.”

Why Gripnr’s (real-world) characters matter.

One of the most important people at Gripnr is its president and head of product, Patrick Comer. In a call with Gizmodo, he was perfectly pleasant, generous with his time, and happy to answer questions. He is not a scammer, he’s not looking to create a get rich quick scheme, and he clearly, obviously, loves Dungeons & Dragons. But he also comes across as naïve: A puppy with Web3 access, millions in his bank account, and no game design experience.

Comer is a constant defender of Gripnr on Twitter. But beyond promoting his own company, Comer isn’t particularly active in any online tabletop role-playing game community. According to his bio on the Gripnr Discord, he’s a lifelong D&D player, but that’s all been done in private games. He has no game credits, has not appeared as “Patrick Comer” on any public game plays, and (far less important, but still telling) he never tweeted about TTRPGs before 2021.

Excluding its lead game designer, the other members of Gripnr’s corporate leadership–CEO Brent McCrossen, creative director Kyle Mortensen, Chief Community Consultant Jacqueline Rosales, and CTO Luke Ledet–have no public ties to the TTRPG world. Mortensen and Rosales, according to Comer, are not gamers at all.

All of this fails to instill confidence in the TTRPG community that Gripnr is the right group to design an on-chain TTRPG protocol.

Jay Dragon of Possum Creek Games has spent the last four years developing games and establishing a massive following in the indie gaming scene. Possum Creek is the award-winning publisher of games like Wanderhome and Sleepaway, and was recently identified as one of Fast Company’s “top ten most innovative companies in gaming.” But Dragon told Gizmodo that “Gripnr is total garbage in the worst way.”

“It’s so openly the result of someone trying to combine every single nerdy thing they can think of with their new shiny Web3 scam toy in an attempt to find some way to make money,” Dragon said. “On a game design side, it both fails to justify itself and spends time inventing new problems which it again fails to solve, which in an era of true innovation and growth in TTRPGs, genuinely sucks to see.”

Without any real ties to the business of creating and distributing TTRPGs, the Gripnr team appear as carpetbaggers, trying to make money by inserting themselves into a community and introducing a scheme that will make just a few people money, including, of course, themselves. Comer confirmed that as is the practice at other tech startups, everyone working for the company will get Gripnr NFTs: “Like Oprah,” he said, miming her infamous gestures, “you get an NFT! You get an NFT!”

Gripnr says that it is “designing in the open,” but has released few details about the way their games will work. The company also says that “100% of mint revenue will be placed in the Gripnr treasury,” and that “all funds will be used to continue to build the company, the protocol and the world.” But it doesn’t offer specifics, and the company declined to detail where that money will actually go, whether to artists, software support, or even gas fees.

Another one of Gripnr’s stated goals–to provide a way for underserved creators to find blockchain success–is not something that is listed as a priority until Phase 8 of the current plan. And the company’s current leadership (five men and one woman, all white) reflects poorly on a desire to commit to diversity. Both Comer and McCrossen are based in New Orleans, a city where 77% of the population are persons of colour.

Gripnr is, definitively, Comer’s brainchild. He’s the one taking lead on the project. But he’s so close to this project that he may be unable to see its flaws. When Gizmodo raised some of the issues described here with him, he listened, but seemed to take the critique less as a list of fundamental problems, and more as puzzles yet to be solved. For now, he seems to be single-mindedly pushing Gripnr through playtesting, hoping that with enough meetings and fixes, everything will work itself out.

This is bad gaming, and you should feel bad.

One of the most basic problems with Gripnr is that it’s simply bad game design. By developing a protocol to prioritise real-world capital gains, Gripnr is fundamentally changing how players are expected to interact with the rules of the game. It’s not just D&D with a blockchain layer, it’s Gripnr the game.

Gripnr demands the construction of new software to emulate character sheets which can easily be made on paper, in word processing software like Google Docs, or in any number of digital toolboxes, including the officially-licensed D&D Beyond. The product Gripnr is attempting to create already exists in multiple forms, for many different games, across many different systems, including old-fashioned print-and-play gaming. The “problems” that Gripnr is trying to solve — problems that Gripnr calls “fundamental opportunities” — are to give players the ability to “prove” their successes via blockchain verification, and to bring monetary value to the table via NFTs. But these aren’t issues that players are demanding to see fixed.

“I play in programs at stores, at conventions, and in home groups,” says Abadia. “I don’t agree [that these are] problems players are looking to solve. These read, to me, as schemes designed to play with financial valuation for the purposes of Gripnr’s self-enrichment, rather than an actual desire to create a sound offering that contributes to the game. I’ve never had to certify what level my character was… and it’s [not] worth my time to play with anyone who wouldn’t trust me.”

Gripnr’s first “fundamental opportunity,” blockchain verification, falls short because there’s no actual certification of achievement, either from Wizards of the Coast or any other authority, there’s just a line on an NFT receipt. Whatever authority Gripnr hopes to assign their NFTs is fallible due to the fact that they are relying on trust-based human inputs, human review, and human understandings of a tabletop roleplaying game that is, at its core, about improvisation.

The second “fundamental opportunity,” bringing tangible value to players, is problematic because the value of TTRPGs is not in the things, but the experience. Players don’t value their favourite character because it has a rare sword; they value it because of the story of how they got the sword, and how they will make more great stories using it in the future. D&D is supposed to be fun, not financially productive.

Some of the best game nights come from “the way we form memories, and the stories build upon themselves in our heads,” said Aiden Moher, an author and gamer who has a book about Japanese RPGs coming out later this year. “What’s better than reminiscing about that epic showdown against a gold dragon last summer? I don’t need or want an immutable record of each turn — I want the joint memories carried by me and my table mates. It doesn’t matter if those memories are detail-filled or fully accurate. It’s about the emotions and personal connections in the moment.”

One particularly troubling part of Gripnr’s game design comes from the structures meant to protect the community from “bad actors,” or people fixing a game so they can make more money. Gripnr plans to have GMs monitor games in order to make sure that nobody is playing to (pardon the pun) game the system, despite the fact that gaming the system to earn money is exactly the goal that Gripnr has set up within their protocols. Their games will exist for the sake of making money, and when players are actively working towards creating a product, you remove core D&D gameplay incentives from the table.

What is the demonstrable capital value, then, in having your character break down in fear and panic instead of mindlessly attacking a monster? What will happen when a GM wants to give out a particularly overpowered item to a rogue, knowing they will misuse it for fun? Or what if they give it to a paladin, hoping to provide narrative tension within a group of chaotic players? What about going off the rails? Going to the moon? Going to meet god? What happens when a GM wants to go off script and just have fun with it?

Gripnr is over-engineering a game which has, as one of its fundamental tenets, the ability to throw away the rulebook and just do what’s going to be fun. By restricting outcomes and enforcing limited character gain, Gripnr is incentivising railroading. In The Glimmering, fun is allowed, but only on Gripnr’s terms, in Gripnr’s system, on Gripnr’s protocols.

Comer admits that he can’t expressly limit GM’s ability to adapt the story to the characters, but he says there will be “limits to the loot people will get” from any game. This is still a limitation that restricts the GM’s ability to make sure the game serves the players first.

The review process, regardless of the level of oversight, will force GMs to railroad their games for fear of having their NFT burned, or being expelled from a community they’ve invested real money to join. These GMs, regardless of talent, will be little better than video game narrators who invite people to act out their interactions, but still force them into predetermined outcomes.

D&D is built on the idea of collaboration. It’s deliberately designed to encourage players to work together. To add capital value to their interactions risks creating out-of-character conflict of interest within the game itself. If another character gets to make the killing blow, will that raise their level instead of mine, thus making their character worth more on OpenSea? If I find something first, will my character be more valuable than my neighbour’s? While some of this conflict exists in the game already, it is strictly limited to the characters, and not the players. All gold in D&D is fictional, after all.

“When the most ‘optimal’ action to increase the character’s value is one that impacts other people’s experience of the game, but consideration over whether it would be harmful to the other players or characters isn’t factored in, then it quickly can become a toxic, unsafe, and not fun experience for anyone,” says Kienna Shaw, a game designer and Ennie-winning co-creator of the TTRPG safety toolkit. “Ultimately a game should be fun and safe for everyone at the table, and this style of competitive self-focused play doesn’t support that.”

There’s also an issue of personal investment. Normally, if any given D&D player feels like they aren’t being treated fairly, they don’t have to return to the game and they lose only time spent. The sunk cost is low. But if a Gripnr player feels like they’re not being treated fairly, they stand to lose much more. Some might feel as if they have no choice but to continue playing D&D even if they aren’t having fun, because they they need to get their money’s worth, or they need to get their character up to a certain amount of value before they cash out. The blurring of the boundary between real-world harm and in-fiction harm fundamentally undermines the design of the game itself.

Gripnr is also operating on the assumption that people who play D&D will want to purchase a pre-minted character to play in the game, ignoring the intricacies that come along with in-game mechanical character development. How many players use a pre-made character in their games beyond the first few learning sessions? Most D&D games have folks making specific and considerate advancements to their character for an endgame that makes sense within their narrative.

Again, Gripnr seems to fail to understand the play culture they are hoping to exploit. The problem is that their much larger goal — to provide an entry for on-chain gaming for the TTRPG community — ignores the backlash that other communities, and the TTRPG community itself, have already issued against blockchain projects.

Gripnr is not a maverick in the TTRPG industry; rather, it’s a pet project attempting to exploit a hobby by creating a centralised protocol of diminishing returns on investments that will only appreciate with non-sustainable, continual buy-in from new investors, while simultaneously contributing to the death of the planet. It devalues the very reason people play games — to have fun — in favour of capital exchange. Ultimately, the very structure of Gripnr resembles a pyramid scheme in D&D clothing.

When Comer spoke to i09, he got the most excited and joyful when he described how he’s teaching his children to play Dungeons & Dragons. When his oldest had a milestone birthday, she threw a D&D party and ran an adventure for her friends. “And you know what monster they ran into?” he asked, grinning, so proud of his kid: “A baby gelatinous cube! How cute is that?”

“That’s what I love about D&D,” he said, “the ability to get creative with it. The ability to just… put anything out there and play the game with your friends.”

I don’t think he sees the irony.