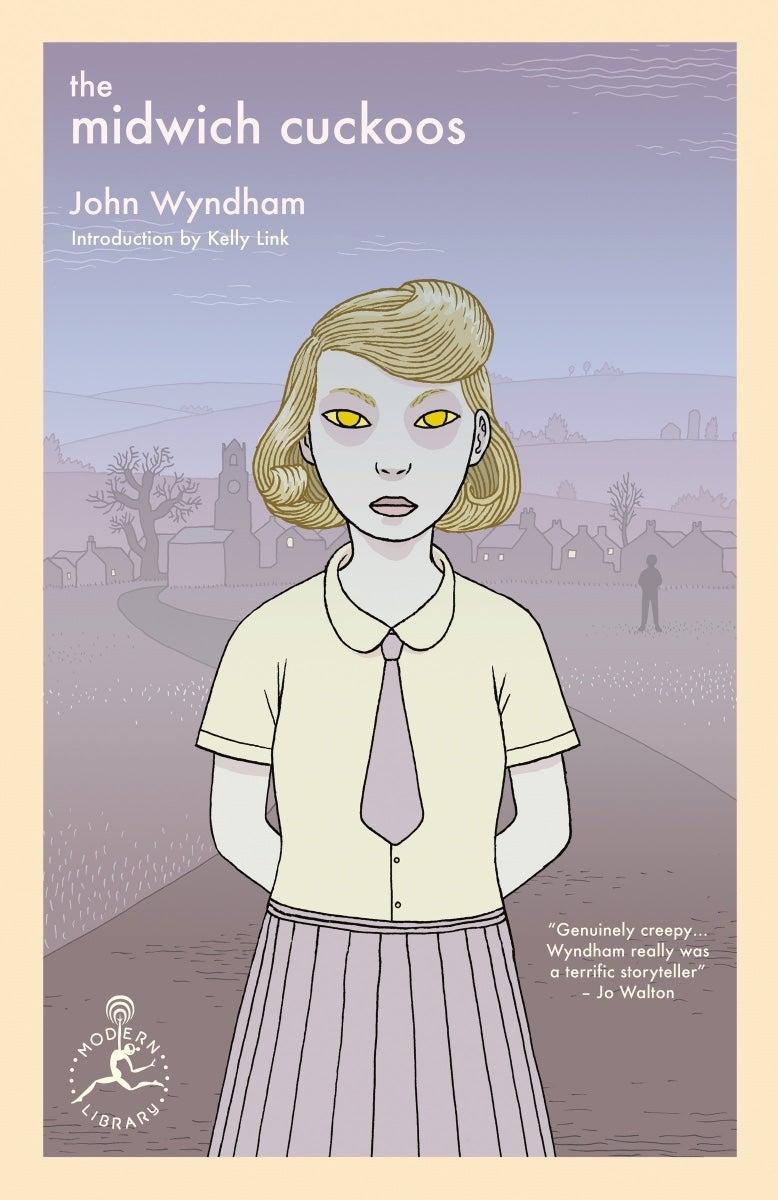

Adapted for the screen in both 1960 and 1995 as Village of the Damned, John Wyndham’s eerie 1957 sci-fi novel The Midwich Cuckoos is getting a republish along with a number of his other works, including Day of the Triffids and The Kraken Wakes. Today we’ve got a look at Cuckoos, featuring the new cover by Anders Nilsen and introduction by acclaimed author Kelly Link, plus an excerpt from the original book. Beware the children!

INTRODUCTION by Kelly Link

John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris was born in 1903 in the West Midlands. Between 1927 and 1946, he had a modest success as a writer of mystery novels and science fiction in the vein of H. G. Wells. Having a good many names at his disposal, he published these under various combinatory pseudonyms. During this same time, he began to sell short stories to the burgeoning, popular American science fiction magazines, as well as persuad- ing his younger brother, Vivian Beynon Harris, to take up writing thrillers.

He served in several capacities during World War II: as a censor in the Ministry for Information, a firewatcher during the Blitz, and as cipher operator during the Normandy landings. When the war ended, he returned to writing under the name John Wyndham, and the first Wyndham novel, The Day of the Triffids, found a wide readership. At one point, Wyndham was the bestselling author of science fiction in the United Kingdom and Australia, though he preferred the term “logical fantasy” to describe his fiction. This, to my thinking, plants him firmly in the category of science fiction, a genre whose practitioners habitually come up with new labels to describe their approach to narrative. Wyndham’s reputation today rests upon four science fiction novels written in a single decade whose subjects, broadly, are ones which sum up the anxieties of their era: apocalypse, invasion, and mutation.

Wyndham’s novels were published during what critics call the Golden Age of Science Fiction. They appear during the same period as Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, whose Martians are “golden-eyed,” uncanny, and — in at least one story, “The Third Expedition” — practical murderers like the children born to the women in Midwich. As well, there are Robert Heinlein’s politically astute, parasitical aliens in The Puppet Masters, the telepaths in Theodore Sturgeon’s More Than Human, the invading mimics of Jack Finney’s The Body Snatchers, the refugee-seeking aliens of Zenna Henderson’s stories of “The People,” and Jerome Bixby’s classic short story “It’s a Good Life,” in which a three-year-old boy with godlike powers telepathically controls a small Ohio town which he has cut off from the rest of the world, sending those who displease him “into the corn field.” But though Wyndham’s short stories appeared in the same pulp magazines as the stories of these other writers, his success at the time is more comparable to the success of Nevil Shute’s On the Beach. Novels like The Midwich Cuckoos appealed to a popular audience outside of a genre readership in much the same way that books by writers like Stephen King and Margaret Atwood (both fans of Wyndham) have an audience outside the genres they draw on.

Wyndham’s narrators usually operate at a comfortable remove from the main event, observers rather than actors, and Richard Gayford, the narrator of The Midwich Cuckoos (and like Wyndham, a veteran of World War II) is no exception. Gayford begins the novel by praising his and his wife’s good fortune in that they were not home in Midwich on the night of September 26. It’s a gripping beginning, in part because of the pains Gayford takes to make it clear to the reader how ordinary and inconsequential Midwich is, a sleepy village of no great interest to anyone who does not live there. What happens isn’t even noticed until the morning of the 27th, when it becomes clear that any person or animal who passes into a radius surrounding two miles with Midwich at its centre falls instantly asleep. When they can be extracted, they wake and seem to be unaffected by the experience. Military Intelligence cordons off the area, begins investigations with the aid of various animals including canaries, dogs on long leads, and a pair of ferrets. A plane flying over Midwich during this period photographs a large shape “not unlike the inverted bowl of a spoon,” which has subsequently disappeared by the morning of the 28th, when the peculiar spell which has lain over Midwich dissipates and the inhabitants wake up again. Several months later the sixty-five women in Midwich who are of childbearing age discover they are pregnant, and nine months later they give birth to children who do not resemble their mothers but only themselves: boys and girls with golden eyes, silvery skin, and fair hair.

The novel has something of the feel of a locked-room mystery, where the reader is given access to the answers almost immediately after the questions are posed. The question of whether or not Midwich has been visited by an alien craft is disposed of quickly in the affirmative. When the pregnancies are discovered, Midwich’s resident intellectual and writer of popular philosophy, Dr. Gordon Zellaby, lays out the likelihood that what has happened is xenogenesis, or brood parasitism — the sixty-five women are incubators for alien children. The town, aided by Military Intelligence, do their best to conceal all of this strangeness from the rest of England and the world, though we find out later that similar events have occurred across the globe. Zellaby posits that a slow invasion is occurring by way of these changeling babies, cuckoos meant to replace the human race.

Early on, the children are revealed to have strange powers.

When one boy is taught in isolation how to extract a candy from a puzzle box, all of the other boys acquire this new ability. The boys, it turns out, make up one group mind, while the girls form another group mind. They can exert mental control over their mothers and, as it turns out, the rest of the human population of Midwich. They aren’t particularly capricious in the use of these powers: babies compel their mothers to breastfeed them, or to bring them back to Midwich when these mothers decamp for various reasons. But in most respects these are well-behaved, quiet, precocious children from the point of view of Gayford and Zellaby. We are never shown the children from the perspective of one of their mothers, or human siblings, only told how, after a period of time, the children go to live and attend school communally at a place called The Grange, supervised by the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health. Zellaby, who participates in their education, continues to keep a watchful eye on them.

He theorizes to Gayford and others that a struggle is coming, once the children are mature, and that the human race is in grave peril. When at last one of the children speaks to Zellaby about their vision of the future, it turns out that Zellaby is correct: the alien cuckoos, like Zellaby, anticipate a kind of arms race which they, more intelligent and with uncanny abilities, will win.

The Midwich Cuckoos functions as a kind of fairy tale, or fable, in which catastrophe is narrowly averted by a clever and heroic trick. It has genuine moments of uncanniness and terror, such as when a group of women attempt to leave Midwich for the next town to do shopping and so on, only to find that they cannot step foot onto the bus. It’s easy to see how the fantastic element functions as a metaphor for our uneasiness about future generations, how they will regard us, how they will care for us, how they will remake the world. It’s possible to read these cuckoos as stand-ins for Soviet sleeper agents, or something close to the ideal child of the Hitler Youth (blond, regimented, disciplined, devoted to something anti- thetical to English society and culture).

But it’s also curious how human Wyndham’s cuckoo children are, despite their golden eyes. They have excellent manners! They enjoy sweets and films. Too, they are in agreement with Zellaby as to whether or not humans and aliens may live, long-term, in peace. Like Zellaby, they are waiting for what their maturity will enable them to do, and they admit freely that they have not come in peace. Like humans, they have a Darwinian view of nature.

Wyndham is a brisk, unsentimental writer. I don’t know that I find The Midwich Cuckoos “a cosy catastrophe,” as genre critic and novelist Brian Aldiss disdainfully puts it, but it does wrap up neatly, leaving me with any number of questions, none of which Zellaby seems to have been interested in, despite his long observation of the children. For example, how do the alien children know what their purpose is to be? Why do they so closely resemble humans? Is the alien race they are the ambassadors of similiarly human in appearance and patterns and thought, or have they been genetically engineered to blend in with their host families? What region of the universe do they come from? What do they want with the Earth, and do they represent a kind of first attempt at conquest? And why do the two group minds break along the gender divide? For my own satisfaction, I imagined Dr. Zellaby might have been writing a book on the cuckoos, containing answers to these and other questions, which his wife and Gayford discover beyond the ending we are given.

Some of these questions may have remained with Wyndham as well, as he began work on a sequel, which was to be called Midwich Main. Though he gave up on this project, there are nevertheless any number of artistic descendants that pick up the themes of The Midwich Cuckoos and other Wyndham novels. I can see traces in novels like Ira Levin’s The Boys from Brazil and The Stepford Wives, Stephen King’s The Tommyknockers and Under the Dome; and, more generally, in television programs like Dr. Who, where time after time the application of intelligence proves capable of defeating hostile forays from other worlds.

It seems worth noting that this new edition comes out after two years and counting of a global pandemic. As I read The Midwich Cuckoos on this occasion, I felt a little like the inhabitants of Midwich: unable, for some periods of time, to leave my town, and wary of what the future might look like. When I first read it, I was a teenager and the idea of sinister pregnancies and eldritch children seemed a reasonable thing to fear. Now I find I wonder about the Midwich cuckoos — how might they have remade the world?

— MacArthur “Genius Grant” fellow Kelly Link is the author of the collections Get in Trouble, Stranger Things Happen, Magic for Be-ginners, and Pretty Monsters. She and Gavin J. Grant have co-edited a number of anthologies, including multiple volumes of The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror and, for young adults, Monstrous Affections. She is the co-founder of Small Beer Press. Her short stories have been published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, The Best American Short Stories, and Prize Stories: The O. Henry Awards. She has also received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Link was born in Miami, Florida, and currently lives with her husband and daughter in Northampton, Massachusetts.

Twitter: @haszombiesinit

NO ENTRY TO MIDWICH

One of the luckiest accidents in my wife’s life is that she happened to marry a man who was born on the 26th of September. But for that, we should both of us undoubtedly have been at home in Midwich on the night of the 26th–27th, with consequences which, I have never ceased to be thankful, she was spared.

Because it was my birthday, however, and also to some extent because I had the day before received and signed a contract with an American publisher, we set off on the morning of the 26th for London, and a mild celebration. Very pleasant, too. A few satisfactory calls, lobster and Chablis at Wheeler’s, Ustinov’s latest extravaganza, a little supper, and so back to the hotel where Janet enjoyed the bathroom with that fascination which other people’s plumbing always arouses in her.

Next morning, a leisurely departure on the way back to Midwich. A pause in Trayne, which is our nearest shopping town, for a few groceries; then on along the main road, through the village of Stouch, then the right-hand turn on to the secondary road for — But, no. Half the road is blocked by a pole from which dangles a notice, road closed, and in the gap beside it stands a policeman who holds up his hand. . . .

So I stop. The policeman advances to the offside of the car, I recognise him as a man from Trayne.

“Sorry, sir, but the road is closed.”

“You mean I’ll have to go round by the Oppley Road?”

“ ’Fraid that’s closed, too, sir.”

“But — ”

There is the sound of a horn behind.

“ ’F you wouldn’t mind backing off a bit to the left, sir.”

Rather bewildered, I do as he asks, and past us and past him goes an army three-ton lorry with khaki-clad youths leaning over the sides.

“Revolution in Midwich?” I inquire.

“Manoeuvres,” he tells me. “The road’s impassable.”

“Not both roads surely? We live in Midwich, you know, Constable.”

“I know, sir. But there’s no way there just now. ’F I was you, sir, I’d go back to Trayne till we get it clear. Can’t have parking here, ’cause of getting things through.”

Janet opens the door on her side and picks up her shopping-bag.

“I’ll walk on, and you come along when the road’s clear,” she tells me.

The constable hesitates. Then he lowers his voice.

“Seein’ as you live there, ma’am, I’ll tell you — but it’s confidential like. ’T isn’t no use tryin’, ma’am. Nobody can’t get into Midwich, an’ that’s a fact.”

We stare at him.

“But why on earth not?” says Janet.

“That’s just what they’re tryin’ to find out, ma’am. Now, ’f you was to go to The Eagle in Trayne, I’ll see you’re informed as soon as the road’s clear.”

Janet and I looked at one another.

“Well,” she said to the constable, “it seems very queer, but if you’re quite sure we can’t get through . . .”

“I am that, ma’am. It’s orders, too. We’ll let you know, as soon as maybe.”

If one wanted to make a fuss, it was no good making it with him; the man was only doing his duty, and as amiably as possible.

“Very well,” I agreed. “Gayford’s my name, Richard Gayford. I’ll tell The Eagle to take a message for me in case I’m not there when it comes.”

I backed the car further until we were on the main road, and, taking his word for it that the other Midwich road was similarly closed, turned back the way we had come. Once we were the other side of Stouch village I pulled off the road into a field gateway.

“This,” I said, “has a very odd smell about it. Shall we cut across the fields, and see what’s going on?”

“That policeman’s manner was sort of queer, too. Let’s,” Janet agreed, opening her door.

…

We locked the car, climbed the gate, and started over the field of stubble keeping well in to the hedge. At the end of that we came to another field of stubble and bore leftward across it, slightly uphill. It was a big field with a good hedge on the far side, and we had to go further left to find a gate we could climb. Halfway across the pasture beyond brought us to the top of the rise, and we were able to look out across Midwich — not that much of it was visible for trees, but we could see a couple of wisps of grayish smoke lazily rising, and the church spire sticking up by the elms. Also, in the middle of the next field I could see four or five cows lying down, apparently asleep.

I am not a countryman, I only live there, but I remember thinking rather far back in my mind that there was something not quite right about that. Cows folded up, chewing cud, yes, commonly enough; but cows lying down fast asleep, well, no. But it did not do more at the time than give me a vague feeling of something out of true. We went on.

We climbed the fence of the field where the cows were and started across that, too.

A voice hallooed at us, away on the left. I looked round and made out a khaki-clad figure in the middle of the next field. He was calling something unintelligible, but the way he was waving his stick was without doubt a sign for us to go back. I stopped.

“Oh, come on, Richard. He’s miles away,” said Janet impatiently, and began to run on ahead.

I still hesitated, looking at the figure who was now waving his stick more energetically than ever, and shouting more loudly, though no more intelligibly. I decided to follow Janet. She had perhaps twenty yards’ start of me by now, and then, just as I started off, she staggered, collapsed without a sound, and lay quite still. . . .

I stopped dead. That was involuntary. If she had gone down with a twisted ankle, or had simply tripped I should have run on, to her. But this was so sudden and so complete that for a moment I thought, idiotically, that she had been shot.

The stop was only momentary. Then I went on again. Dimly I was aware of the man away on the left still shouting, but I did not bother about him. I hurried toward her. . . .

But I did not reach her.

I went out so completely that I never even saw the ground come up to hit me. . . .

From the book THE MIDWICH CUCKOOS by John Wyndham. Copyright © 1957 by John Wyndham. Reprinted by arrangement with Modern Library, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

This new edition of John Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos will be available April 19; you can order a copy here, and check out Modern Library’s other Wyndham releases here.

Editor’s Note: Release dates within this article are based in the U.S., but will be updated with local Australian dates as soon as we know more.