Forget dinosaurs engaged in vicious combat. Put aside terrifying fangs and claws. Scientists have discovered a softer side to dinosaurs: the reptilian equivalent of a belly button.

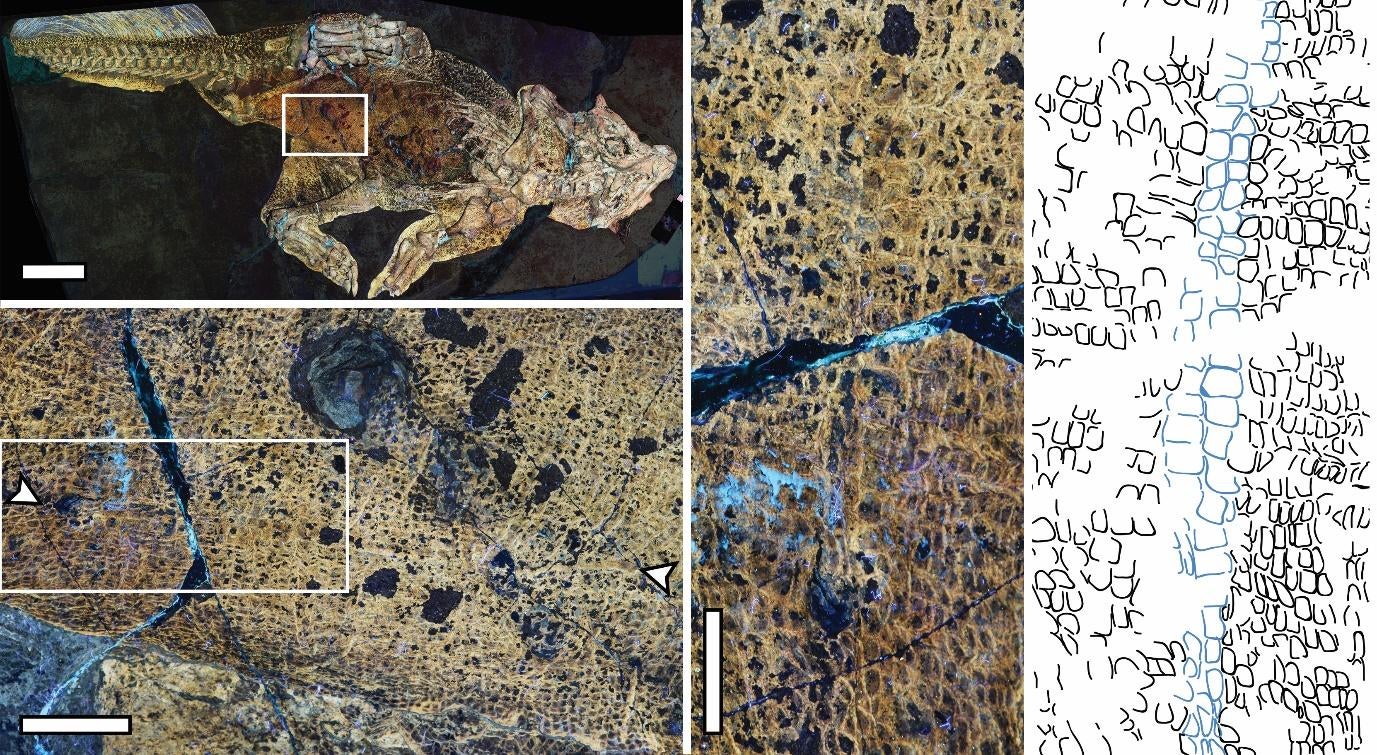

For the first time ever, scientists have identified an umbilical scar on a non-avian dinosaur. The paper announcing this find is published in BMC Biology, and it’s yet another exciting discovery from a particularly rare and well-preserved Psittacosaurus fossil from China. (Other delights from this same specimen include a cloaca and countershading camouflage.)

For mammals, belly buttons are the result of a detached umbilical cord at birth. But reptiles and birds, whose reproductive method is to lay eggs, have no such cord. Inside an egg, the embryo’s abdomen is connected to a yolk sac and other membranes. The scar occurs when the embryo detaches from those membranes directly before or as it hatches from the egg. Known as an umbilical scar, it is the non-mammalian form of a belly button. And that is exactly what the international team of scientists claims to have found on this fossil.

Psittacosaurus, a bipedal dinosaur that lived during the beginning of the Cretaceous, is an early form of ceratopsian, a type of beaked herbivore that would, later in that same geologic period, include Triceratops. Perhaps the most dazzling fossil of the species yet found remains frozen in time, lying on its back, complete with skin and tail bristles. Its preservation, at approximately 130 million years of age, is breathtaking. And although made known to the public in 2002, it continues to break new and unique ground.

Michael Pittman has studied this particular fossil in detail. He’s a paleobiologist, assistant professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and co-author of the new paper. He and co-author Thomas G. Kaye, from the Foundation for Scientific Advancement, were able to visit the fossil in Germany in 2016 at the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt. The two scientists invented Laser-Stimulated Fluorescence (LSF), a relatively new imaging technique. With this non-destructive method, they have been able to reveal details in fossils that might otherwise remain unseen.

This “subtle scar,” as Pittman described it in an email, was found using LSF. And it is thanks to LSF that the team could study the scales of the skin — their patterns, wrinkles, and any scarring — in exquisite relief. For help working on the skin, the team turned to Phil Bell, dinosaur paleontologist at the Palaeoscience Research Centre, University of New England in Australia, who has considerable expertise on the subject. Bell is lead author of the new paper.

“LSF brings out the detail in spectacular fashion,” Bell said in a video interview. “It really looks as though the animal could get up and walk away. You can see every little wrinkle and bump in the skin. It looks so fresh. Imagining these animals as living, breathing entities, rather than just dead skeletons, is what fascinates me. Bringing them to life is one of the major goals of my work.”

The team did find evidence of wrinkled skin, but not in the abdomen where the umbilical scar is located. Healed injuries would display regenerative tissue; there would be a distinct break in scale patterns, with smooth granulation tissue over the injured area.

Instead, explained Pittman, “[t]he umbilical scales have regular sizes, smooth margins, and are arranged along the midline of Psittacosaurus. This suggests that the scar was not a result of an injury.”

In order to determine the dinosaur’s age, most would cut into the bone. The extreme rarity of this fossil means researchers want to avoid any such destructive analysis. So the team compared the length of its femur to those of other Psittacosaurus specimens and estimated that this particular animal was about 6 or 7 years old. In other words, this dinosaur was nearing sexual maturity.

Not every reptile or bird living today maintains an umbilical scar through adulthood. The authors note that one particular exception is the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis). In addition, some scarring is a result of yolk sac infections in birds or crocodiles raised in poor conditions. With all these variables, it’s not a given that all dinosaurs — or even all Psittacosaurus — would have an umbilical scar.

Pittman described how he and Kaye “collected a huge library of LSF data from the Psittacosaurus specimen in 2016,” which they are still combing through and studying. “This led to a paper that year on an observed countershading camouflage pattern, the first identified in a dinosaur. We planned to analyse the LSF data further because our images provided so much extra information about the skin.”

“We are currently finalising a detailed description of the skin of Psittacosaurus,” he added. “This required us to look at every square inch of the fossil.” And that is how this umbilical scar discovery occurred.

Looking at preserved skin in such detail is Bell’s area of expertise. He explained that few scientists focus on fossil skin, thereby making any research prone to exciting discoveries. Moreover, he said, when speaking with the general public, he finds that they are often surprised to hear that fossil skin exists at all, let alone what it reveals. Even within paleontology, he says, the overriding focus continues to be on bones.

“I think the take-away is that scaly reptiles are interesting,” Bell said. He hopes that both the public and the larger scientific community realise how much we have yet to learn about dinosaur skin and its biological function. Noting that “the skin is the largest organ in the body,” he referenced how, for example, scales protect modern reptiles from dehydration and UV rays. Bell wants to change the perception that scales are less exciting than feathers.

“It’s an absolutely stunning specimen,” Bell remarked of the Psittacosaurus fossil. “And the fact that it’s still yielding surprises 20 years [from the time] it was first announced to the public is extraordinary, and that’s because of the development of these new imaging techniques.”

Those surprises — the knowledge we have gained thus far — would not have been possible had the fossil remained in private hands. This gorgeous Psittacosaurus specimen has a controversial history. Its exact provenance is unknown, as it moved from one private collector to another before its purchase by the Senckenberg. Then, as now, there are those who hope the fossil will be repatriated to China. At the end of their paper, the authors write: “There is ongoing debate regarding the legal ownership of this specimen and efforts to repatriate it to China have not been successful. Our international team of Australian, Belgian, British, Chinese and American members all hope for and support an amicable solution to this ongoing debate. We think it is important to note that the specimen was acquired by the Senckenberg Museum to prevent its sale into private hands and to ensure its availability for scientific study.”

Jeanne Timmons (@mostlymammoths) is a freelance writer based in New Hampshire who blogs about paleontology and archaeology at mostlymammoths.wordpress.com.