Apple is one of the most globally respected technology companies, having built its reputation on creating reliable, high-end products with innovative features. The Cupertino tech giant has such an impressive track record that its next project — whether that be an AR headset or something else entirely — is already assumed to be a success.

Nowadays, everything Apple touches seems to turn to gold, from its ubiquitous iPhones to the new Macs with custom M-series silicon and even a subscription streaming service that went from “the one with the soccer show” to an award winner with a respectable catalogue of original content.

With all the praise Apple receives, it can be easy to forget about the company’s many failures, some of which never made it to market. Apple is now the richest tech company in the world, but its ascendance wasn’t without its setbacks, some of which put the company on the brink of bankruptcy. Some of these ill-fated devices were either poorly realised or overly ambitious — but nearly all of them influenced the devices Apple users enjoy today. And you might be surprised to learn about, or perhaps remember, some of the more recent failures.

With that said, let’s flip open the lids of our PowerBook 100s and take a look back at some of Apple’s worst products. Oh, and if you like learning about consumer tech history, read our articles on the worst failures from Microsoft and Google.

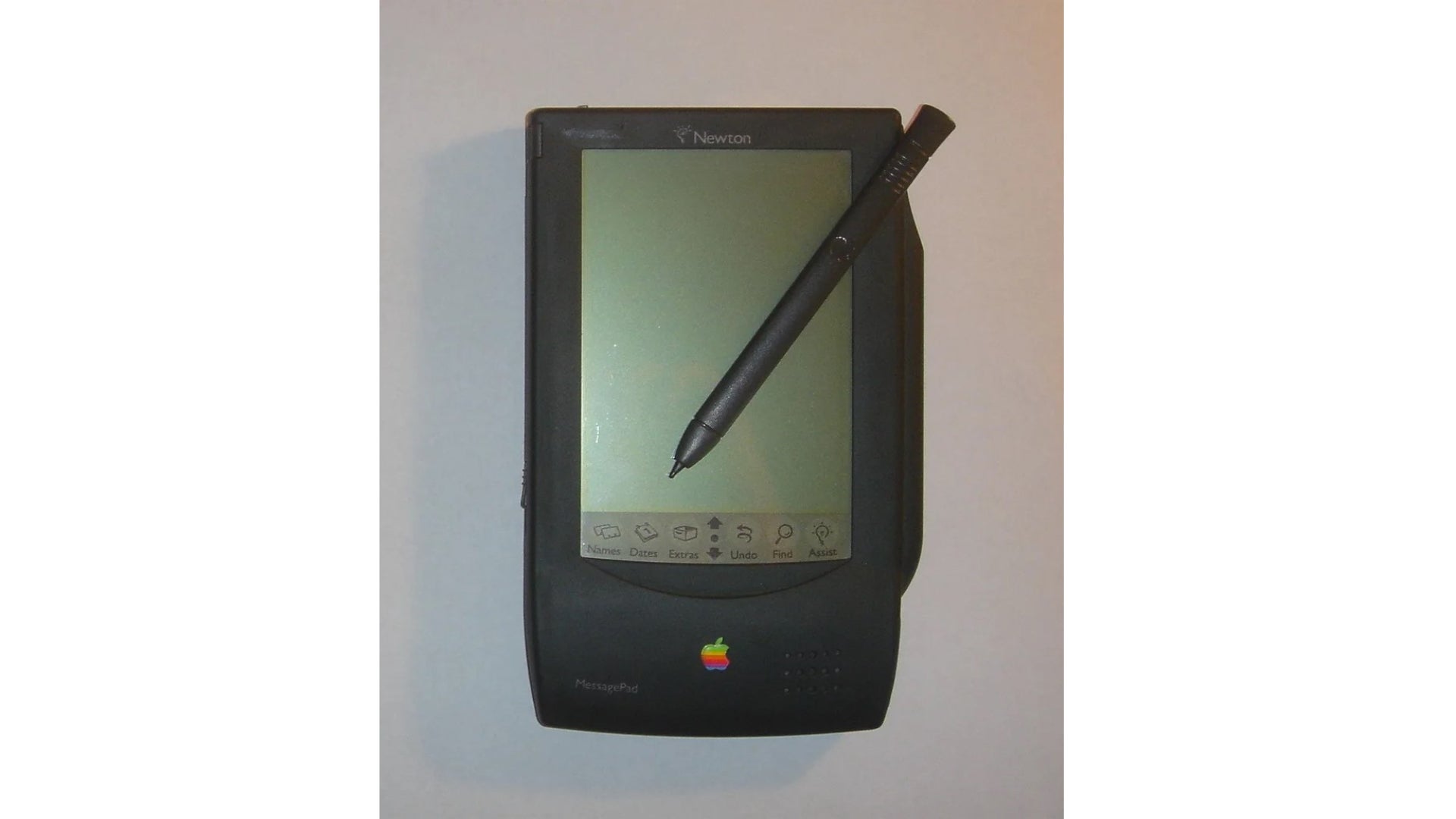

Apple Newton

Once upon a time, Apple needed a big idea, and it came in the form of a portable computer that could fit in your pocket. No, not the iPhone–that would come later. First, there was Newton. Though it wasn’t the earliest compact digital organiser, the Newton MessagePad was the first to be dubbed a “personal digital assistant,” or PDA. It was a pocketable rectangular device with a small touch-screen that you could interact with using an included plastic stylus.

As is often the case, the development of the Newton is even more interesting than the product itself. One of the biggest hurdles to creating such a device was finding a chip that didn’t need much power and didn’t produce much heat. It turns out a British company called Acorn had cracked that nut with a new CPU design.

Apple invested $US3 ($4) million dollars into Acorn to help revise its chip, the Acorn RISC Machine, or ARM. With this injection of resources, Apple, Acorn, and Acorn’s chip partner VLSI spun off the chip division into a new company called Advanced RISC Machines and created the ARM610 CPU that would power the Apple Newton. ARM-based chips now power more than 160 billion devices, including Apple’s latest Macs.

Eventually, these elements came together to form the Apple Newton platform, which was first revealed to the public at CES in 1992 to much fanfare. The original Newton MessagePad (H1000) would go on sale in 1993 with basic features like a calculator, calendar, and notoriously poor handwriting recognition. Though some of its components would later be adopted by the iPhone, the Newton was a commercial failure until it was killed off in 1998 by a returning Steve Jobs who famously hated the device.

What to learn more about the history of Apple Newton? Read the full story here.

Apple USB Mouse (Hockey Puck)

Cute doesn’t mean practical. Dubbed the “Hockey Puck” for its odd circular shape, the Apple USB Mouse was a tragically flawed peripheral. Instead of making a tried-and-true ordinary mouse with two clickers, Apple’s first-ever USB mouse had a single button at the top of its Roomba-shaped housing.

The design was simply terrible. The shape couldn’t have been less ergonomic, and since it didn’t have an obvious top and bottom, orienting your cursor was unnecessarily tedious. The cord was too short, the mouse was too small, and it wasn’t built particularly well, either. Apple slapshot the hockey puck out of existence after two years.

Here is what Gizmodo alum Sam Rutherford had to say about the mouse:

“But the truly worst thing about the original iMac was its mouse. Seemingly designed purely for looks, Apple’s one-button monstrosity is possibly the least ergonomic peripheral I’ve ever used. It felt like you were trying to move the cursor around by pushing a hockey puck, and even though in hindsight I appreciate Apple’s use of a cord sporting USB, the cable on the iMac G3’s mouse was hilariously short, too.”

Apple Pippin

The Pippin had a short but fascinating history, starting as a way for Apple to expand into the multimedia market and ending as a failed gaming console created by Bandai.

Let’s jump back to the early ‘90s, a few years after Steve Jobs was ousted and during a particularly tough phase in Apple’s history. Looking to expand into more households, Apple created an open hardware platform based on the Macintosh operating system. It was described at the time as a “trimmed-down Macintosh” running classic Mac OS and powered by a PowerPC processor. This was not a retail product, but a platform Apple intended to licence out to different companies that could make it their own with modifications. It could be used for education, as a home PC, or as a multimedia hub.

Leading toy maker and game developer Bandai stepped up to the plate, evolving Apple’s “Pippin Power Player” prototype into the Pippin Atmark game console in Japan and Pippin @World in the US. Running on a PowerPC 603 32-bit processor with 6MB of RAM, the Pippin Atmark/@World wasn’t the most powerful system, but it did have some innovative features, including an NTSC/PAL switch, a boomerang-shaped controller, games that could be run on a Mac desktop, and support for a full-size keyboard.

The console flopped, and apart from a small licence deal with Norweigan company Katz, Apple found no other suitors. There were three main reasons why the Pippin failed: it launched at $US600 ($833) (more than $US1,000 ($1,388) today!), there were few compelling games to play (especially in the US), and Sony, Sega, and Nintendo already had a stranglehold on the market.

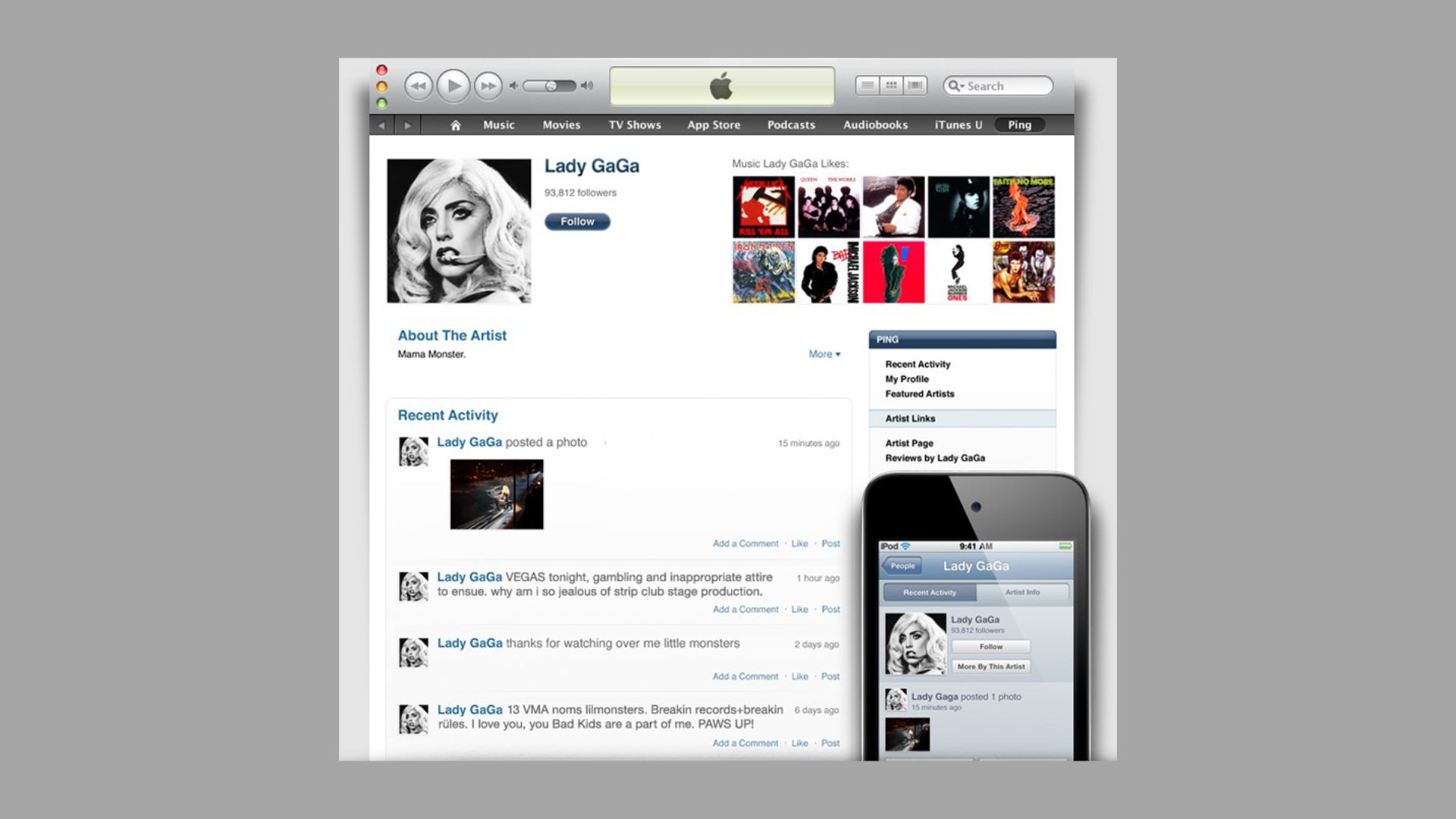

iTunes Ping

Social media meets music library. That was Ping, the failure of an experiment baked into iTunes 10. Released in 2010, Ping seemed to be an immediate success, with Apple claiming 1 million users within the first 48 hours. The goal of this feature was to bridge the divide between artists and listeners, giving everyday users a way to interact with their favourite musicians and share music with friends. Ping had all the ingredients of a regular social media network: a news feed, followers, and multimedia content. Heck, when Steve Jobs revealed the platform, he succinctly described it as “sort of like Facebook and Twitter meet iTunes.”

I can speculate about all the reasons Ping failed, but the bottom line is that it just didn’t catch on with users. Ping was limited in scope, it launched without Facebook integration, and it didn’t provide anything different from the other social media networks besides a focus on music. Ping was shut down two years after it launched, with Jobs bluntly stating, “the customer voted and said ‘this isn’t something that I want to put a lot of energy into.’”

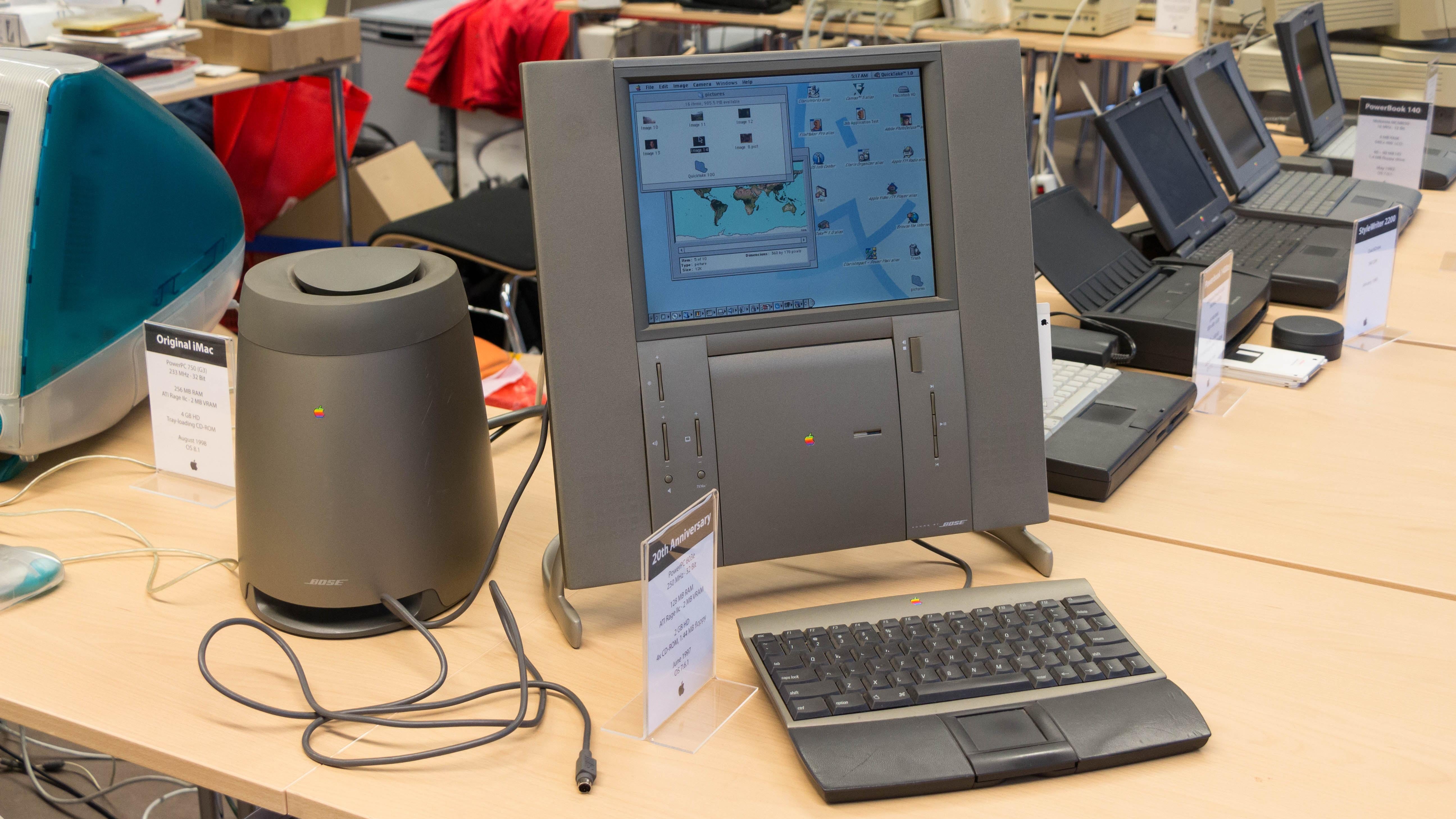

Twentieth Anniversary Macintosh

Released to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Apple Computer, the Twentieth Anniversary Macintosh, better known as TAM, was a technical showcase packed with the latest technology. Not exactly meant for mainstream consumers, the computer was a luxury item unlike anything else Apple had released up to that point.

The TAM had an awkward flat shape with computer inputs and a CD drive on the lower half and a 12.1-inch active-matrix LCD display on the top. It was meant to be the ultimate all-in-one: a computer, a TV (with a built-in tuner), and a radio (with an FM tuner). The thing even shipped with a massive Bose subwoofer. As for the computer components, the TAM had a PowerPC 603e CPU running at 250MHz, two RAM slots for up to 128MB, a 2GB storage drive, and ATI 3D Rage 2 graphics. Apple still has a specs page for the Twentieth Anniversary Macintosh on its official website.

The TAM failed due to a familiar problem: it was too damn expensive. When it was first unveiled at the Macworld Expo in 1997, the company estimated the price at around $US9,000 ($12,494), with concierge setup service included. It was released a few months later at a reduced $US7,499 ($10,410). That wasn’t enough to sway customers, and prior to discontinuing the product after just one year, the price further dropped to $US1,995 ($2,769). So few were sold that they have become collector’s items, now listed at up to $US20,000 ($27,764).

Butterfly Keyboard

The story of Apple’s most widespread modern technology failure began in 2015 when the company released the 12-inch MacBook with a keyboard that used low-profile “Butterfly” switches. While the ultra-slim notebook was generally well-received, its stiff, lifeless keyboard was one of the most widespread criticisms (along with limited ports) among journalists and customers.

Using a new keyboard mechanism on the MacBook made sense–Apple needed to reduce the size of certain components to accommodate the diminutive size of the 12-inch notebook. Despite the criticism, Apple stuck with it, later bringing Butterfly to the MacBook Air and MacBook Pro. In doing so, it swapped an acclaimed tactile keyboard with one that made it feels as if you were typing directly on a desk.

Poor comfort isn’t what ultimately killed the Butterfly keyboard. The death blow was its uncharacteristically terrible reliability. The switches were so frail that any piece of debris or dust that got stuck underneath could break a key, resulting in missed key presses or double presses. Failures were widespread, causing customers to flock to Apple stores so their systems could be disassembled and repaired. Don’t think the Butterfly keyboard was that bad? Read this WSJ piece by Joanna Stern (or Joanna Stn on a Butterfly Keyboard) in which she deftly illustrates the problem.

Apple’s response was sluggish and frustrating. For years, the company stubbornly made small tweaks to the keyboard before implementing an “extended keyboard service program,” giving users four years of warranty. It wasn’t until 2020 with the release of the new MacBook Pro 16 that Apple started phasing out the Butterfly–long after the reputational damage was done.

Macintosh TV

Bringing new meaning to the term “all-in-one,” the Macintosh TV was part desktop, part television. The idea is that you could save space, and ideally money, by purchasing a desktop that could double as your television. At the heart of this machine was a Macintosh LC 520 powered by a 32 MHz Motorola 68030 processor, a measly 5MB of memory (upgradable to 8MB), and a 160MB hard drive. The kicker, besides its wonderful and now exceedingly rare all-black chassis? A built-in 14-inch Sony Trinitron CRT TV running at a 640 x 480-pixel resolution.

Today, you can watch TV in a separate app or browser window while you continue to work on your computer. Back then, you weren’t so lucky. The Macintosh TV was either-or: pressing the “TV/Mac” button on a credit card-sized Sony remote that shipped with the PC changed your inputs from Mac to TV. So you could be playing Pacman on the TV and then get right back to work on your Mac with the press of a button. That was pretty sweet back then, especially if you were a college student huddled in a small dorm. It was also pricey, selling at $US2,099 ($2,914), or about $US500 ($694) more than the comparable Colour Classic II.

In the end, the Macintosh TV was slower and more expensive than other options on the market, and it lacked core features. Apple ended up shipping only 10,000 units before discontinuing the Macintosh TV four months after its release.

Apple III (or apple ///)

The Apple III (styled as apple ///) was a commercial failure that put Apple in a difficult position in its early days. Following the massively successful Apple II, this third-gen model was built primarily for businesses as a way for Apple to gain a foothold in the market before the arrival of the IBM PC a year later. Rather than build off the previous model, Apple chose to create an entirely new system with a full keyboard, a display with 80-column text, and an enhanced operating system. It also needed to run existing Apple II software.

The goal was to win over the commercial sector and gain 90% of the market, effectively phasing out the Apple II. Unfortunately, the computer suffered from severe reliability issues. The motherboards reportedly overheated due to the lack of a cooling fan (something Steve Jobs supposedly removed for aesthetic reasons). As a result of engineering and product management woes, the computer had “100% hardware failure,” according to a Steve Wozniak interview featured in Byte magazine. Revisions were made but the damage was done, and Apple would go on to sell an estimated 65,000 units.

The Apple III was the first computer not built by Wozniak, who wrote in his 2007 book iWoz that the Apple III failed because it was “not developed by a single engineer or a couple of engineers working together. It was developed by committee, by the marketing department.”

AirPower

The one that never was. What makes AirPower such a fascinating failure is that Apple teased this product to the public, something the company would only do if it were confident about bringing it to market. We knew exactly how AirPower was going to look, how it would work, and it had a name! Heck, the media even got hands-on time with non-functioning prototypes.

The moment Apple wishes it could take back occurred on September 12, 2017, during the launch of the iPhone 8, iPhone 8 Plus, iPhone X, and AirPods charging case. On stage, Apple promised a “lot of good devices” would come onto the market as a result of wireless charging being added to the iPhone 8 and iPhone X (to be fair, wireless charging had already been around for years). Apple wanted to join in on the fun by releasing the wireless charger to rule them all: a pad that could simultaneously power three devices — say, a phone, wireless earbuds, and a smartwatch.

Apple told us to “look for the AirPower charger next year,” but 2018 came and went without any updates. Instead of adding more details, references to AirPower faded away from its website in Back to the Future fashion. Then reports surfaced about the trouble Apple was having engineering the pad. Anyone who has used Qi charging knows that charging one device wirelessly generates considerable heat. Placing two more gadgets on a multi-coil surface, it turns out, was a fire hazard. It wouldn’t work up to the standards Apple set, and in March 2019, Apple cancelled AirPower.

iPod Hi-Fi

I don’t blame you for forgetting about the iPod Hi-Fi, even if it’s among the more recent of Apple’s failed products. Before the wireless HomePod and HomePod mini, Apple released a room-filling speaker called the iPod Hi-Fi. It was an attractive, high-end device with powerful sound quality, a six-button remote, and simple controls.

Unlike the wireless speakers we use today, the iPod Hi-Fi was a speaker hub with a 30-pin connector for your iPod. When it entered the market, there were already some great options that delivered even better sound quality and video output at less than the $US350 ($486) price Apple was asking. Another issue is that the speaker was called “hi-fi” and made big claims about audiophile-grade sound despite it being for everyday users–that sort of talk ruffled a few feathers. It didn’t sell well and was quietly discontinued less than two years after launch.

Copland

By 1994, Apple’s System 7 operating system was showing some age. Apple needed to make some major overhauls to snatch attention away from the upcoming Windows 95 OS, which flaunted modern multitasking and dynamic memory allocation.

Copland, a new OS set for release as System 8 in 1996, was supposed to be a saving grace. Instead, it was one of the worst IT disasters in history. When you boil it down, Copland failed because it was overly ambitious — a sour example of feature creep. Basically everybody at Apple wanted in, and Copland became so bloated that a working version never arrived despite Apple promising at WWDC 1996 to ship the OS to developers within months.

Core features of Copland included protected memory, a “live search” in the toolbar, improved multitasking, themes, multi-user support, native PowerPC integration, and a feature for minimising windows by dropping them to the bottom of the screen. It was a revolutionary upgrade that never materialised.

In late 1996, Apple announced that it had purchased NeXT and was bringing Steve Jobs back in an advisory role. With the merger, Apple gained the Unix-based NeXTSTEP operating system, which would become the foundation of Mac OS X. Many of the features set for Copland were incorporated into subsequent versions of Mac OS.

Power Mac G4 Cube

Designed by Jonathan Ive, the Power Mac G4 Cube was a miniature desktop suspended in an attractive acrylic housing to give the illusion of a floating computer. The futuristic-looking machine had no fans and used passive cooling through a large vent on the top. It was a beauty, despite the comparisons it received to a tissue box or paper shredder.

On the inside of the base model was a PowerPC G4 processor, 64MB of RAM, a 20GB HDD at 5,400 rpm, and an ATI Rage 128 Pro video card. The higher-end version had a 500MHz processor, 128MB of RAM, and a 30GB drive. Critical reception to the Power Mac G4 Cube was mostly positive, with most praising its gorgeous design.

The reason for its failure was simple: the cube didn’t provide the power or features one would expect for the price. That price, by the way, was $US1,799 ($2,497) at launch and $US1,499 ($2,081) after a price cut. Apple admitted sales for the Power Mac G4 Cube were lower than expected. Actually, one-third of what it had anticipated, leading the company to cease production one year after launch.