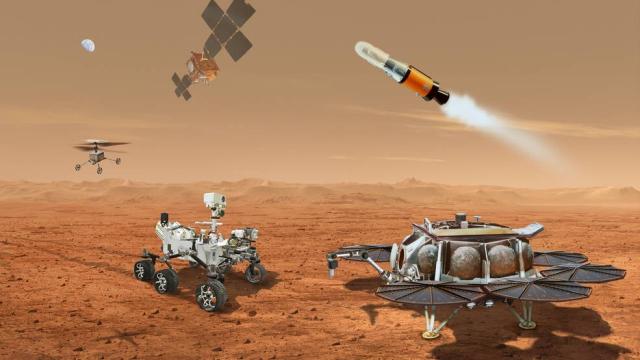

NASA press conferences are almost always interesting, but today’s media event truly blew my mind. Instead of using a proposed sample fetch rover to collect surface samples left by NASA’s Perseverance rover, the space agency intends to send two Ingenuity-class helicopters to Jezero Crater on Mars, where they’ll fly to the sample tubes, scoop them up, and bring them to a lander waiting nearby.

NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) are still in the conceptual design phase of the Mars Sample Return Program, so changes are to be expected. But the alterations announced today were fairly substantial. The two space agencies have finished the systems requirements review of the upcoming mission, in which some elements were removed and others added.

Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA, compared the Mars sample return mission to the newly commissioned Webb Space Telescope, describing them both as international missions with historic implications. Indeed, bringing Martian surface samples to Earth for analysis would be huge, both in terms of the resulting science and the experience we would gain from such an endeavour. In addition to learning more about the Red Planet’s geology, the samples could yield evidence of ancient Martian life. And as David Parker, director of Human and Robotic Exploration at ESA, told reporters, the return mission would allow for absolute age dating of Martian samples, which is currently not possible. What’s more, the enterprise would serve as a “precursor mission” for a crewed expedition to the Red Planet, Parker added.

Like Webb, the Mars Sample Return mission is immensely complex; nothing like this has ever been attempted before. Technically, this mission is already underway. Perseverance is currently gathering and storing surface samples at Jezero Crater, placing tiny bits of rock into small tubes that either get placed into the rover’s onboard carousel or plopped onto the Martian surface. To date, Perseverance has collected and sealed 10 tubes filled with rock samples, and an 11th tube is in the process of being stored. NASA and ESA are in the midst of deciding the best way of gathering these tubes and returning them safely back to Earth.

The newly announced revision to the mission architecture is not subtle. Still on the menu is NASA’s Sample Retrieval Lander, which will carry the Mars Ascent Vehicle, and the Earth Return Orbiter, which will be equipped with NASA’s Capture, Containment, and Return System. These items remain, but NASA and ESA have cancelled plans to send the speedy Sample Fetch Rover and its associated landing platform.

The reason for the change, according to Zurbuchen, has to do with the “excellent performance” of Perseverance and NASA’s other functional Mars rover, Curiosity, which has been working on Mars for nearly 10 years. The risk analysis of the sample return mission “has been affected by the experience of the last year,” he said. NASA now has good reason to believe that Perseverance will still be active in the early 2030s, when the collection phase of the mission kicks in. This wasn’t always clear, Zurbuchen explained, hence the perceived need for a dedicated sample fetch rover. Entirely relying on Perseverance was far from reasonable or realistic, he said. With this added confidence, and with Perseverance continuing to be healthy, NASA and ESA decided to nix the fetch rover, which now casts Perseverance as the primary option for transporting samples to NASA’s Sample Retrieval Lander. Zurbuchen said NASA planners “always wanted to have Perseverance take part in the retrieval part of the mission” and that the revised strategy isn’t a “substantial change” but “rather an evolution.”

NASA and ESA had previously considered launching the fetch rover and the ascent vehicle on two different rockets to reduce risk, but that won’t be necessary, given the cancellation of the fetch rover.

ESA is currently developing the sample transfer arm that will remove the tubes from Perseverance’s carousel and gently place them in the Mars Ascent Vehicle (the rocket that will carry the samples to the orbiter). Speaking to reporters, Parker said the multi-jointed sample arm, which measures 2.5 metres when fully extended, has “always been part of the mission architecture.”

NASA also wants to send two Ingenuity-class helicopters to serve as a back-up contingency, should something go wrong with Perseverance. To date, the Ingenuity helicopter, which landed on Mars with Perseverance in February 2021, has performed 24 more flights than originally planned, as Jeff Gramling, director of the Mars Sample Return Program, explained to reporters. “This showed us the usefulness of rotorcraft on Mars,” he said.

The two helicopters that will be used for the sample return mission won’t be identical to Ingenuity, as they’ll be slightly heavier and feature mobility wheels instead of feet. The small wheels will allow the helicopters to traverse across the Martian surface. What’s more, each helicopter will have an arm for grabbing tubes from the surface. When filled with sample material, the tubes won’t weigh any heavier than 150 grams, which shoulsn’t pose a problem for the helicopters. NASA officials said it’s unlikely that the helicopters will be able to retrieve sample tubes located farther than 2,300 feet (700 meters) from the lander.

During the retrieval phase, the gripper helicopters, operating independently, will fly to a sample tube, land nearby, scoot on over to grab it, and then fly back to the Sample Retrieval Lander. After depositing the tube nearby, ESA’s robotic arm will pick it up and place it into the ascent stage. This will be done methodically until all the sample caches have been collected.

Gramling and his colleagues wouldn’t say if the new plans would reduce the overall mission costs, but as Zurbuchen admitted, the mission, now without the fetch rover and a second lander, is “simpler” and “less organizationally complex.” Previous estimates suggested the project could cost upwards of $US4.4 ($6) billion.

The current plan is to launch the Earth Return Orbiter in 2027 and the Sample Retrieval Lander in 2030. Under this plan, the samples should arrive on Earth in 2033. The program should enter into its 12-month preliminary design phase in October.