Gizmodo is 20 years old! To celebrate the anniversary, we’re looking back at some of the most significant ways our lives have been thrown for a loop by our digital tools.

If you’ve spent any time reading Gizmodo over the past twenty years, there’s probably one governmental agency responsible for more, “wait, really?” headlines than all the others combined. That uneasy accolade, of course, goes to DARPA.

Known more formally as the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency, the Pentagon’s sci-fi R&D wing is responsible for jump-starting some of the military’s most consequential advances in science and technology. Many of those nascent research efforts, like the early predecessors to the modern internet and GPS, eventually mature and find new life as commercial technologies scaled up by private industry and delivered, for a price, to tech nerds around the world. DARPA’s track record isn’t perfect though; for every success story, there are also a handful of hilarious flops (I’m looking at you giant Mechanical mountain robot).

Still, every few decades or so, a truly groundbreaking technology oozes its way out of the DARPA caves and transforms into something deeply emblematic of the time its was created. Whether or not those creations were net positive or negatives for the world depends who you asked.

While sorting through its most societally significant breakthroughs, Gizmodo spoke to multiple DARPA officials, including its current director, reviewed dozens of DARPA documents and scoured through recent books documenting the nutty agency’s history. Here’s what we found.

Autonomous Vehicles

Silicon Valley’s promise of driverless cars weaving through Monday morning traffic to shuttle you to work or snag a bite of takeout has felt “just around the corner” for the better part of a decade, though there’s some reason (cautiously at least) to believe the tech could be maturing beyond buzzword status in 2022. Waymo, Cruise, Aurora, and dozens of other firms are currently testing autonomous fleets with plans to commercialize in the coming years. Large-scale retailers like Sam’s Club already have plans to deliver toilet paper via autonomous trucks and in China, Baidu has already secured a first-of-its-kind autonomous taxi licence. Even the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the U.S.’s largest highway regulator, recently adjusted its crash pass standard guidelines to no longer require steering wheels, brake pedals, or other manual driving controls for so-called autonomous vehicles.

All of those recent examples owe their success, in part, to a flurry of DARPA failures in the harsh Mojave Desert 18 years ago. There, 15 early “autonomous” vehicles competed against each other in DARPA’s first “Grand Challenge.” The terms were simple. Successfully navigate the 229 km desert course autonomously and walk away with a $US1 ($1) million crash prize.

None of the 15 vehicles were able to complete the challenge. Hell, the “best” participant only managed to complete 13 km of the course.

The agency would conduct similar sequel challenges in 2005 and 2007, each with numerous winners.

It might seem odd that an agency whose primary task is developing new material for America’s global war machine would host a gameshow-like AV competition but according to DARPA Director Stephanie Tompkins, the competition’s initial goal was to accelerate then-nascent autonomous vehicle tech which could then later potentially be used to assist troops through driverless convoys in hazardous areas. As Gizmodo noted earlier this year though, the actual implementation of that tech by The Department of Defence has progressed at a snail’s pace.

Tompkins reflected on the early challenges in autonomous driving and said that unlike other DARPA projects narrowly focused on specific military use cases, it was clear early on emerging driverless could potentially “help the world.”

The creative forces behind many of those early sand-filled hunks of junk ended up becoming leaders in their fields and some of the primary driving forces in the burgeoning AV industry some ambitious analysts predict could be worth over $US2 ($3) trillion worldwide by 2030.

“The end of the story hasn’t been written yet,” Tompkins said, speaking about the more recent advances in autonomous vehicles tech. “People are still trying to work through the ethics and legalities.”

DARPA’s interest in autonomous vehicles has extended far beyond four-wheeled cars and trucks in the years since the Grand Challenge. In some simulated events, autonomous fighter jet systems have already outperformed human pilots barreling through dogfights. Back in February a DARPA-owned UH-60A Black Hawk helicopter outfitted with an experimental Aircrew Labour In-Cockpit Automation System (ALIAS) system was able to successfully complete a 30 minutes test flight without a pilot, marking a major milestone in the aerial autonomy space. On the ground, DARPA’s more recent RACER program seeks to advance high-speed autonomous combat vehicles capable of quickly speeding across complex, potentially hazardous terrain.

DARPA’s shift to contests

Crucially the grand challenge wasn’t just a win for autonomous vehicles, it also revitalized DARPA’s public image. Sharon Weinberger, who documented the agency’s history in her 2018 book, The Imagineers of War, argues The Grand Challenge and DARPA’s subsequent shift towards nerd-friendly, sci-fi-inspired projects in the early 2000s were partly a pivot from the agency’s failed push for a controversial surveillance system headed by John Poindexter, the controversial Regan-era admiral found guilty of a cover-up during the Iran Contra scandal.

“The Grand Challenge really saved DARPA,” former DARPA director Anthony Tether told Weinberger. Following pushback from U.S. senators over DARPA’s “Orwellian” surveillance project, the challenge “was one of the greatest public relations efforts…that instantly changed the whole image of DARPA back to where it was.”

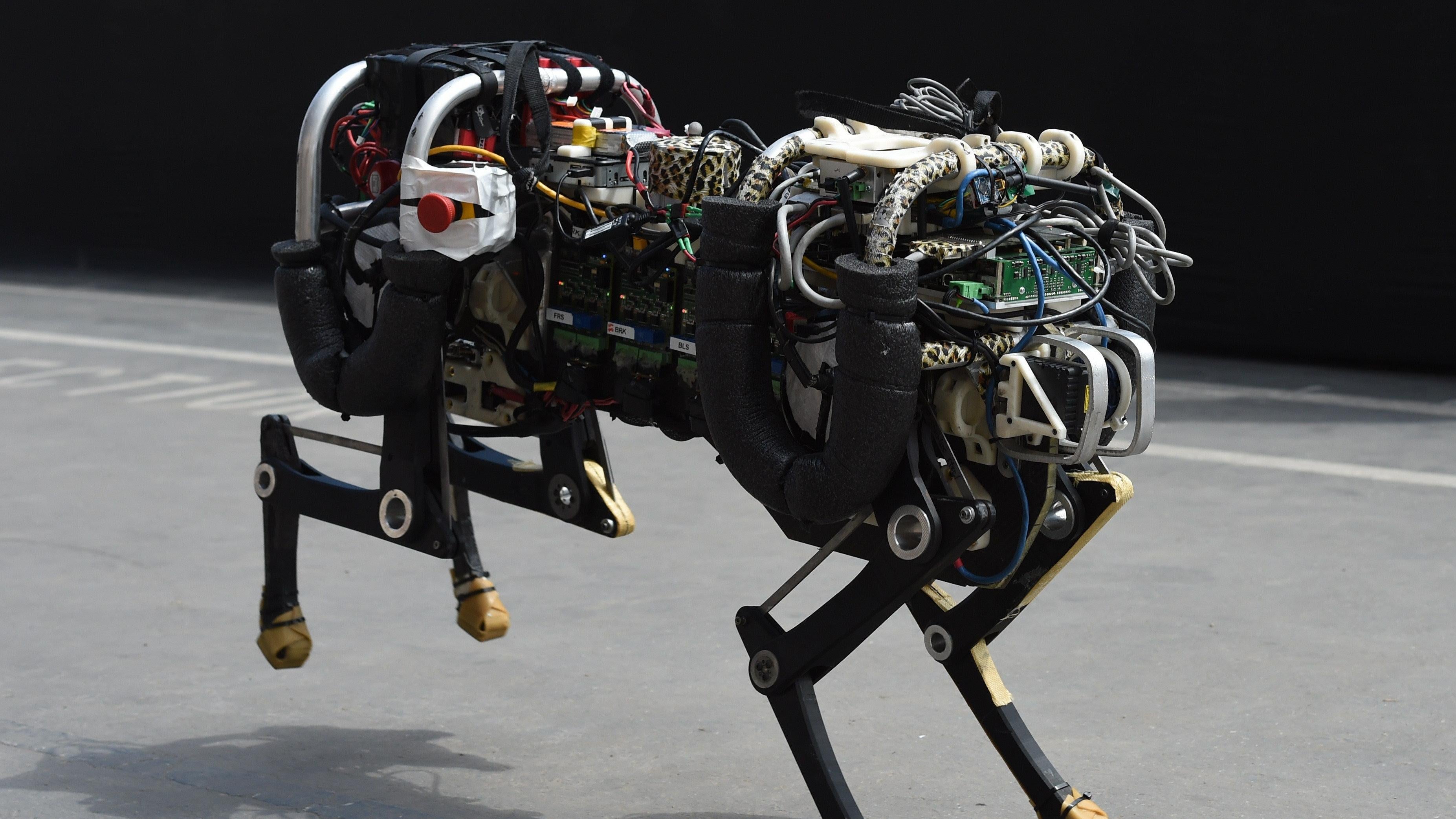

Cash prize challenges like those conducted for autonomous vehicles became staples at DARPA. In 2015, the agency conducted a robotics challenge where many saw the now notorious Boston Dynamics behemoths for the first time. Not long after that, the same concept was applied to cybersecurity defences in the agency’s “Cyber Grand Challenge.”

Vaccine development

A less obvious, but arguably far more consequential DARPA pursuit over the past two decades comes by way of biotech: specifically vaccine development and therapeutics. Though many others have claimed responsibility for the recent surge in RNA vaccines used to combat the Covid-19 pandemic, DARPA director Tompkins said many of the pivotal early advancements within that space emerged from the agency’s ADEPT project. That project was originally intended as a vehicle for rapid vaccine development and therapeutics for overseas military forces but quickly evolved to uses on a much larger scale, mirroring a familiar DARPA trajectory.

DARPA-funded RNA projects at Moderna resulted in the first Phase 1 clinical trial proving RNA could deliver antibodies to protect against viruses. That original proposal involved using RNA to encode things other than just vaccine antigens, but around a decade later the pandemic made that specific use case extremely urgent.

Gizmodo spoke with Doctor Amy Jenkins, a program manager in DARPA’s Biological Technologies Office (BTO) to discuss the ways the agency’s early biotech investments influenced the pandemic’s course. Like autonomous vehicle research before it, Jenkins said the agency’s interest in RNA research was specifically tied to use cases within the military, though potential civilian applications clearly seemed within the realm of possibility.

“What’s good for the DoD, which are by and large healthy 18- to 30-year-olds is gonna be good for the general population as well,” Jenkins said. “We always knew there could be civilian applications and encouraged that with the groups that we funded.”

And while DARPA’s ADEPT program was developed with the explicit thought of a pandemic in mind, Jenkins said the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic and its destructive reality still came as a shock.

Though DARPA ceased funding RNA vaccine research years prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, Jenkins said it was still actively funding work with Moderna looking into monoclonal antibodies. Unlike vaccines that take time to set in, monoclonal antibodies at their best can start preventing disease immediately following an injection. Funding for that project aimed to protect soldiers in the intervening time it takes vaccines to fully kick in but has already led to multiple commercial pharmaceutical products that are available to civilians.

When asked about the outright rejection of the RNA vaccines by some on the political right and broader criticism against companies like Moderna making eye-watering profits after receiving funding from the U.S. government, Jenkins responded by arguing expensive new technologies like RNA may not have been possible without government agencies jumping in to fill a gap left in the pharmaceutical market. This is a common argument made by pharmaceutical companies themselves and there’s plenty of reason to be sceptical of it.

“No company gets rich off of an infectious disease threat,” Jenkins said. “Large pharma and many of them are shutting down their infectious disease divisions because it is just not profitable.” We have seen scattered long-term R&D shutdowns in the pharma industry but the operating principle is a “threat” isn’t going to be very profitable unless it… uh, you know, becomes a global pandemic. In that case: jackpot! Until then, public money is a big help.

“If we want to have these capabilities that allow the U.S. to have access to the life-saving drugs when the time comes then I think it does require government funding to make sure that these technologies are being developed.”

The question of whether that funding should go to a for-profit company remains up for debate, but DARPA is pretty firmly in the “public-private partnership” camp.

Drones

DARPA’s interest in unmanned aerial drones predates the 2000’s but many military and civilian advances made in the unmanned aerial vehicles space over the past two decades stem, at least in some way, from DARPA-related projects. More recently, the agency has shown particular interest in the idea of “drone swarms,” where an infantry soldier could theoretically deploy somewhere between 200 or even 1,000 small, unmanned aircraft systems that interact autonomously to assist in missions.

DARPA’s OFFensive Swarm-Enabled Tactics (OFFSET) researchers have reportedly conducted at least six field experiments with these drone swarms since 2017, with a top official telling FedScoop they believe the U.S military could potentially deploy the tech within five years. The agency’s also investing in novel ways to wirelessly charge that massive drone armada.

On the creepier side, DARPA’s spent time researching much smaller, bird and insect-sized drones ostensibly intended for aerial surveillance. In her 2015 book, The Pentagon’s Brain, Annie Jacobsen details the first “mechanical insect” prototype, a six-inch, 40 gram, camera-attached drone dubbed “Black Widow.” Analysts speaking with Jacobsen said the tiny insect wannabe, which could reportedly fly for 22 minutes before going back to base, could potentially be used for both surveillance and retrofitted with a tiny explosive as a potential assassination device.

In addition to Black Widow, DARPA reportedly designed drones to resemble hummingbirds, bats, beetles and flies, all as part of its biomimetics research, an area of study focused on mechanical systems built to imitate creatures from the natural world. In her book, Jacobsen cites unsettling accounts of anti-war activists attending a protest in Washington D.C’s Lafayette Square in 2017 who claim to have seen an odd swarm of dragonflies monitoring their movement which they claimed, “are not insects.”

Military engagement and sneaky surveillance might offer the most obvious use cases for drones (at least when your job is developing military tech), but they’re not the only ones. DARPA has already begun exploring ways it can use subterranean drones to autonomously navigate, map, and search underground areas like caves and tunnels. DARPA believes advances here will help first responders rescue people trapped in collapsed mines or search for survivors in an earthquake’s aftermath. Hell, they might even be able to find over-ambitious spelunkers.

Just last year, DARPA awarded a team of researchers from various universities a $US2 ($3) million prize for creating robots that were able to investigate an underground passage resembling man-made and natural structures. Those robots were tasked with locating and reporting objects similar to the way they would in a rescue situation. If that sounds simple, keep in mind DARPA apparently rigged the environment with smoke and unpredictable terrain.

“This was the most labour-intensive project I’ve ever been involved in,” Kostas Alexis, a professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and a member of the winning team said in a press release. “We were constantly developing ideas and working across multiple research environments and geography.”

DARPA-fying the body

If autonomous vehicles, biotech research, and new drone technology all represent sea changes in DARPAs’ last twenty years, there are dozens of other new technologies whose full potential remains uncertain. Foremost amongst those are DARPAs’ work on prosthetic limbs, and by extension, brain-computer interfaces and neural inputs.

In 2016, after years of research, DARPA made its LUKE prosthetic arm available to service members. Though rudimentary prosthetics have existed for over a century, DARPA’s project is considered groundbreaking due to its ability to use multiple grips and a variety of inputs all in a device that mimics the same weight and size as a comparable human arm. The device gained FDA approval in 2014, but so far it hasn’t managed to break through into mainstream commercial adoption so far.

DARPA’s also spent the better part of the past decade researching noninvasive, wearable brain-computer interfaces capable of reading brain signals and turning them into inputs on a connected device. Engineers working on DARPA’s Next-Generation Nonsurgical Neurotechnology believe that tech could one day let human soldiers use their brain to interact with unmanned vehicles or activate cyber defence systems. Imagine a soldier piloting a swarm of hundreds of tiny drones instantly using just his brain. From what we can tell, that future’s far off, however DARPA’s early work in BCI has led, if inadvertently to a growing number of startups like Elon Musk’s Neuralink and Meta, which are looking at ways to bring different versions of BCI’s to wide audiences.

Grappling with emerging tech’s unintended consequences

Beyond gizmos and gadgets (which this site has dutifully covered over the years) a select few of DARPA’s tech breakthroughs have also arguably managed to shift the tides of society and culture.

During the agency’s first twenty years, its work on ARPANET, the modern internet’s predecessor, laid the early groundwork for a digital revolution would come to dominate billions of humans’ daily experiences. Some of the downstream effects of DARPA’s more recent breakthroughs, however, feel less universally positive. The agency’s work pioneering drones, for example, likely saved U.S. soldiers’ lives, but it also introduced a new re-evaluation of what’s considered reasonable civilian “collateral damage” and ushered in the new issue of drone pilot PTSD. And as Andrew Cockburn argues in The Kill Chain, the U.S. military’s deployment of DARPA-inspired unmanned drones has radically altered the military’s relationships with “targeted killings,” or as they are referred to by normal folks, assassinations.

Tompkins, DARPA’s director, acknowledged some of those unintended consequences but pushed back to say the agency can’t be expected to always foretell the future.

“I wish that we had a much clearer view of everything that could go wrong but it isn’t possible,” Tompkins explained. In light of that uncertainty, Tompkins said the agency consults with ethicists, philosophers, legal experts, anthropologists, and even science fiction writers to help think about what uncertainties the future could hold. Still, the agency’s inherent role as a test bed of sorts for new tech means their input can only go so far in affecting how the military will ultimately choose to implement a technology. Of course, DARPA’s critics would argue that developing military tech guarantees it will be used for unethical purposes.

The director used the example of brakes on cars, which both provide safety but encourage people to drive faster. “I don’t want to work with anybody that doesn’t wrestle with these things,” she said “We want to lose a little sleep thinking about the consequences.”

DARPA, 2022 and beyond

Looking to the future, Tompkins has spoken enthusiastically about the prospects of materials science, a field DARPA has spent decades dabbling in. Speaking on DARPA’s YouTube channel, Tompkins imagines a future where seemingly nondescript everyday objects will be made with materials consisting of properties that currently seem “completely impossible.” Future engineers, Tompkins posits, could build materials stronger than currently imaginable by manipulating that at the molecular level.

During her interview with Gizmodo Tompkins also highlighted the traditionally unsexy field of supply chain logistics (which has taken a beating during the pandemic) as areas ripe for DARPA innovation. “We’ve got a whole lot of investment in the idea of being able to make the stuff you need wherever you need it.” As an example, Tompkins points to DARPA projects currently attempting to extract water out of desert air and two different programs focused on making food out of recycled plastic or air and water, as well as another attempting to make medicines out of incredibly simple raw materials. These are big bets, but Tompkins says they could very well be remembered in the 2040’s with the same impact current readers ascribe to the stealth bombers and the internet.

“The whole idea is we’re trying to break what today’s world feels like is an impossible problem,” she said. “We might fail, but if we succeed it could be pretty awesome.”