The history of water on Mars flows a lot deeper than scientists once believed. A new project has mapped hundreds of thousands of rock formations on the Red Planet that may have been altered by large amounts of water in the past.

Data from two Mars orbiters was used to create a detailed global map of mineral deposits on Mars, pinpointing where water may have once flowed across the planet. “I think we have collectively oversimplified Mars,” planetary scientist John Carter from the Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale in Paris, and lead author of a paper published in the journal Icarus, said in a statement.

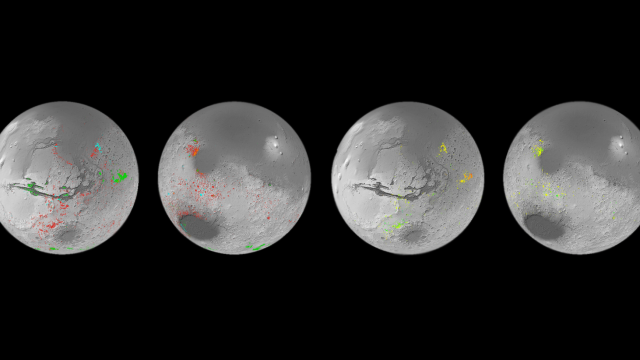

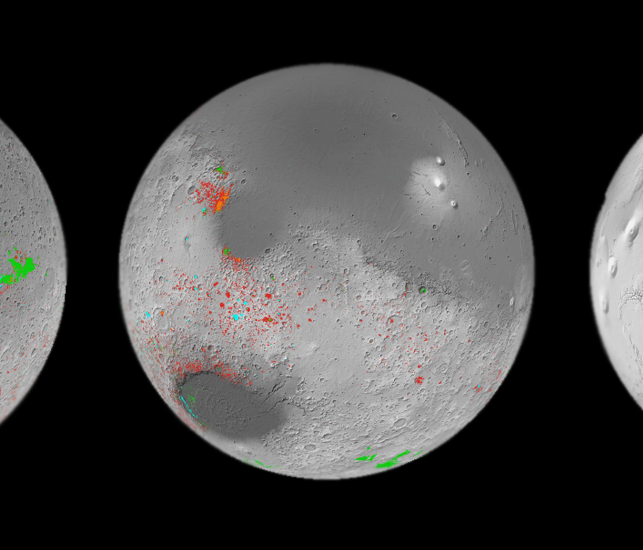

Observations from the European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter and NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter allowed researchers to create the map, a project that took a decade, according to the ESA. Before this work, scientists only knew of about 1,000 rock formations on Mars that contain hydrated minerals. But the new map reveals hundreds of thousands of such outcrops. “This work has now established that when you are studying the ancient terrains in detail, not seeing these minerals is actually the oddity,” said Carter.

Mars is a dry planet today, but various evidence suggests it once had flowing water across its surface. Aqueous minerals can be found in rocks that were chemically altered by water in the past, and typically turned into clays and salts. When small amounts of water interact with the rocks, they remain relatively unchanged and retain the same minerals found in the original volcanic rocks. But if large amounts of water interact with the rocks, then soluble elements are dissolved by the water, leaving behind more aluminium-rich clays.

The new findings suggest that water played a much bigger role in shaping Mars’ geology over the course of its history. However, it’s still not clear whether the presence of water was consistent over time or if there was an ebb and flow of water on Mars over shorter periods in its early history. “The evolution from lots of water to no water is not as clear cut as we thought, the water didn’t just stop overnight,” said Carter. “We see a huge diversity of geological contexts, so that no one process or simple timeline can explain the evolution of the mineralogy of Mars.”

Although the map doesn’t provide all the answers, it does point to places where more clues can be found. The areas identified here will be excellent candidate landing sites for future missions to Mars; some of them may even still have water ice buried beneath the surface.

More: Mars Is Hiding Its ‘Lost’ Water Beneath the Surface, New Research Suggests