“If we begin to feel that we’re being surveilled all the time, our behaviour changes. We begin to do less. We begin to think about things less. We begin to modify how we think.” – Tim Cook

The English language, novelist George Orwell once observed, “is in a bad way.”

The critic and notoriously “crabby” grammarian likened the destruction of the written word to the spiraling depression of one caught up in thrall of alcoholism: “A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and fail all the more completely because he drinks,” he wrote. “It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language.”

The Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel — a survivor of not one, but two Nazi concentration camps — warned us, “No one may speak for the dead.” Were Orwell’s apparition to suddenly to appear, though, it seems plainly obvious how he’d feel about the indelible eponym history posthumously awarded him: “Orwellian” is a word that would grate upon his ears.

It is also a term that, today, significantly hinders our ability to comprehend the realities of the surveillance under which live. It has evolved into precisely the kind of politically-charged drivel that the author himself abhorred; that which consists, as he said, “largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness.”

To wit, practically anything today may be said to be “Orwellian.”

My son just described having to clean his room as positively “Chorewellian.”

— Gennefer Gross (@Gennefer) January 9, 2021

A man receiving a $US35 ($49) fine after being photographed with his dog on a beach: Orwellian. Private companies monitoring productivity in the workplace: Orwellian. Politicians lobbing threats at tech companies online: Orwellian. Media coverage of disease control guidelines: Orwellian. Remote monitoring of students taking exams at home: Orwellian. Schools reviewing camera footage after waking up to find political slogans scrawled across a campus: Orwellian. A publisher backing out of a book deal with a politician for supporting political violence: Orwellian.

Getting banned on social media — you guessed it — Orwellian.

The novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, once one man’s labored warning about the perils of Marxian optimism, begat a literary cliché that has resonated for decades, its meaning warping with each year beyond its title, flying often so high as to touch the sun of satire. Although the book’s depiction of doublespeak retains some ironic value in relation to nonsensical political babble, used in the worst cases to downplay state-sanctioned violence — the pacification of enemies; the enhanced interrogation of detainees — Orwellian is a narrow and reductive descriptor flung today at virtually anything remotely suggestive of surveillance.

For 30 years or more, noted surveillance studies scholar David Lyon has argued for laying the term to rest — though not, he has said, because what Orwell had to say about the threats facing liberal democracies was wrong. Rather, Lyon acknowledges what many others have long felt: that Orwell’s perspective, through no fault of his own, is markedly dated. (Orwell began writing Nineteen Eighty-Four during World War II and published it a few years later, shortly before dying from tuberculosis.)

“I observed that for all that may be learned from Orwell, he could not have guessed at the role that new computer technologies on the one hand and consumerism on the other would play in creating surveillance as it was evolving in the late twentieth century,” Lyon, professor emeritus of sociology and law and former director of the surveillance studies centre at Queen’s University, wrote in 2019.

Lyon wrote that his views on Orwell have since evolved even further. Although the surveillance society once promised had finally arrived, it came not, Lyon said, “wearing the heavy boots of brutal repression, but the cool clothing of high-tech efficiently.” Far from technocratic gaze of Big Brother’s singular menacing telescreen, it manifested via “a million screens of social networking sites and handheld devices marketed as convenient, cost-effective and customised.” That which would be considered surveillant in the “watching-averse” world of Orwell’s characters might be better defined today as first-world luxury.

“Orwell’s characters lived in gnawingly fearful uncertainty about when and why they were being watched,” Lyon writes. “Today’s surveillance is made possible by our own clicks on websites, our texting messages and exchanging photos.”

Like many of his peers, Lyon prescribes rapid linguistic changes to better our perception of our new privacy-free reality. In addition to “Orwellian,” stock phrases like “surveillance state” and even “surveillance society” are definitionally weak, reduced to being the kind of “worn-out metaphors” that Orwell himself decried as lacking any “evocative power.” What’s emerged instead, Lyon argues, is nothing less than a full-blown surveillance culture; a people subdued by technology’s “amazing power,” resigned regardless of cost to suffer its trespasses, what he referred to as “the octopus tentacles of global intelligence and policing networks [and] the subtle and seductive sirens of corporate marketing.”

Google Trends reveals search interest in the term “Orwellian” reached its highest peak in November 2020, coinciding with an appearance by Trump White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany on the morning talk program “Fox and Friends.” Referring to state-level health mandates aimed at forestalling an anticipated spike in covid-19 cased effected by holiday travel — which ultimately did ensue — McEnany said, “I think a lot of the guidelines you’re seeing are Orwellian.” (Trends charts search results as far back as 2004.)

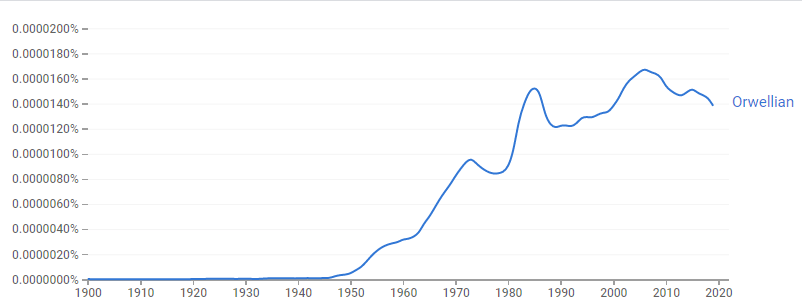

Meanwhile, Google’s Ngram Viewer — a search engine charting word frequencies from a corpus of more than 8 million books (or roughly 6% of all books ever published) — shows use of the term peaking in printed works during the latter half of 2005, declining back to a level of use just prior, and immediately after, the year 1984 itself. (The corpus currently excludes books published after 2019.)

The cause of the spike in Google’s text corpora would require further investigation, but notably coincides with the “unprecedented” expansion of police surveillance powers in the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks, leading up to the revelations that the Bush White House had, in 2002, authorised the National Security Agency (NSA) to eavesdrop on Americans placing telephone calls and sending email messages overseas.

The appearance of “Orwellian” in print gained additional steam following the whistleblower disclosures of Edward Snowden, the former NSA contractor, who revealed the U.S. government’s sweeping collection of domestic phone records and harvesting of internet browsing activity. (Snowden, who was labelled a “traitor” by successive administrations — with Joe Biden stubbornly refusing to comment on the matter — remains stranded in Russia, where he sought asylum.)

Like Lyon, surveillance scholars John Gilliom and Torin Monahan, in the introduction to their 2012 book SuperVision, lay waste to “Big Brother,” inviting us to abandon the concept entirely, alongside misleading, “simplistic dichotomies,” such as “surveillance vs. privacy” or “privacy vs. freedom”. Surveillance, the authors write, no longer represents “brief intrusion or a scary idea from a movie,” but “our way of life.”

Similarly, English professor Peter Marks, in his own exhaustive study of surveillance depicted in film and literature, notes the menagerie of surveillance technologies revealed during the Snowden affair “bore little resemblance” to those of Orwell’s imaginings. To Orwell, the “brave new World Wide Web, social media, mobile phones and body scanners, identity theft and GPS tracking, let alone the aggregation and assessment of Big Data by governments and corporations, was unknown and unknowable,” Marks writes.

Many media writers have likewise registered opinions on how inaccurately applied “Orwellian” is most contexts. Each seems to have their own unique but sound rationale for considering it garbage. Linguist Geoffrey Nunberg noted in 2003, for instance, that the ter paid little homage to Orwell the person, “as a socialist thinker, or for that matter, as a human being.” Commemorating only two of his five novels (and none of his nonfiction), the connotation behind “Orwellian” Nunberg said, reduces the writer’s palette “to a single shade of noir.”

Culture writer Constance Grady, meanwhile, bemoaned its overuse across much of the Trump era. Frequent mentions in the press and liberal invocation by partisan rivals ensured years of sudden, erratic spikes in the book’s sales, forcing it, at one point — 72 years after publication — to the top of Amazon’s book charts. Users of the term, Grady lamented, “are indulging in precisely the kind of lazy and dishonest obfuscation Orwell railed against.”

“If thought corrupts language,” Orwell believed, “language can also corrupt thought.”

Surveillance culture today might be best be viewed as the inevitable byproduct of what privacy scholar Julie E. Cohen termed the age of “informational capitalism.” (Or what Harvard professor Shoshana Zuboff coined, more narrowly, “surveillance capitalism.”) The corporations that have thrived under this new, sociotechnical paradigm have done so chiefly by harnessing what Cohen’s contemporaries (Federal Trade Commission chair Lina Khan and Yale law professor Amy Kapczynski, among others) refer to as “platform power,” the monopolistic systems under which a handful of retail and advertising companies maintain unprecedented gatekeeper control over modern modes of interpersonal exchange, and the very stores of human knowledge.

In his essay, Politics and the English Language, Orwell observed that “an effect can become a cause, reinforcing the original cause and producing the same effect in an intensified form, and so on indefinitely.” Likewise — in a cycle as spiraling as Orwell’s metaphoric drunk — the surveillance culture produced by informational capitalism is now the very fuel on which informational capitalism thrives.

Profit-maximizing amid an information gold-rush, the Amazons, Googles, and Facebooks of the world have learned to bait, manipulate, and coerce nearly the whole of society into knowingly exposing itself to all manner of personal and financial harm. Through a conscious campaign of what Israeli linguist Guy Deutscher onced called “linguistic degeneration,” corporations have rendered the word “privacy” itself altogether meaningless. What, if anything, serves as a better representation of the Orwellian concept of doublethink than the so-called “privacy policy,” a term which simultaneously describes how one’s privacy is safeguarded and simultaneously exploited in endless ways for profit.

“The invasion of one’s mind by ready-made phrases,” Orwell once wrote, “can only be prevented if one is constantly on guard against them, and every such phrase anesthetizes a portion of one’s brain.”

We have long found ways to banish “silly words,” as he called them, relegating them to the trash heap of time, purging from our lips forever, “not through any evolutionary process,” he said, “but owing to the conscious action of a minority.”