Debut fantasy author Emily H. Wilson’s Sumerians Trilogy offers a fresh take on the oldest story of all: The Epic of Gilgamesh. First entry Inanna focuses on the goddess of love and the people she meets during a fraught time for ancient Mesopotamia. The novel’s not out until August of next year, but Gizmodo has the gorgeous cover and an excerpt to share today.

First, here’s a synopsis of Inanna:

Stories are sly things…they can be hard to catch and kill.

Inanna is an impossibility, the first full Anunnaki born on Earth in Ancient Mesopotamia. Crowned the goddess of love by the twelve immortal Anunnaki who are worshipped across Sumer, she is destined for greatness. But Inanna is born into a time of war. The Anunnaki have split into warring factions, threatening to tear the world apart. Forced into a marriage to negotiate a peace, she soon realises she has been placed in terrible danger.

Gilgamesh, a mortal human son of the Anunnaki, and notorious womaniser, finds himself captured and imprisoned by King Akka who seeks to distance himself and his people from the gods. Arrogant and selfish, Gilgamesh is given one final chance to prove himself.

Ninshubar, a powerful warrior woman, is cast out of her tribe after an act of kindness. Hunted by her own people, she escapes across the country, searching for acceptance and a new place in the world.

As their journeys push them closer together, and their fates intertwine, they come to realise that together, they may have the power to change to face of the world forever. The first novel in the stunning Sumerians Trilogy, this is a gorgeous, epic retelling of one of the oldest surviving works of literature.

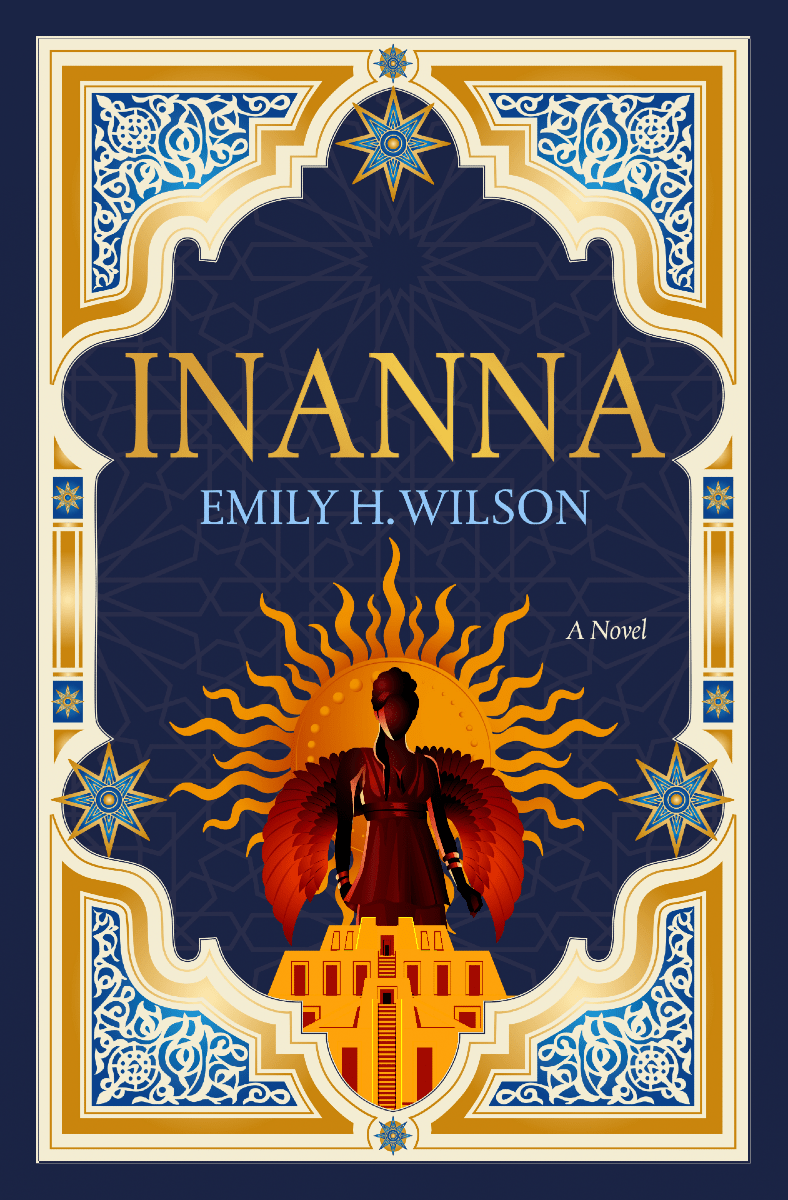

Here’s a look at the full cover, designed by Julia Lloyd, followed by the excerpt from Inanna’s first chapter.

I was born in the city of Ur, in the springtime. In those days memories of the Great Flood were still raw, and everything was measured from it. So I can tell you that I was born six years after the deluge, when the land was dry and true again, but the dead were still every day missed.

It was in many ways an ordinary beginning. My mother screamed and raged, and then pushed me out, through blooded thighs, onto linen sheets. She held me to her chest and wept. My father knelt beside her all the while, his hands in prayer before him. The midwife took me from my mother and laid me down in an ancient cradle. She counted my toes and fingers, and put her ear very gently to my chest.

Yet of course we were not an ordinary family.

When the Anunnaki first descended from Heaven, the dazzling sunlight blinded them. All of them speak of it, of the shock of Earthlight, scouring out their eyes. Their vision returned but with it came the gaudy blues and nauseating greens that were Earth’s true colours. And the noise! The screeching birds and crashing waves, clawing at their nerves. The air itself was an assault upon them, renewed at every breath. For a long time, they did not know if they could survive here.

And so now my mother looked at me, so small and frail in my cradle, and she was terrified for me.

Oh, but I did live. Indeed I thrived, in the scouring Earthlight. I grew plump, beneath Earth’s garish, cobalt sky. In my first gasp I breathed in the cedars in the palace gardens and the salt of the ocean. I breathed out for the first time to the music of the frogs upon the marshland. All of it was bliss to me. What had been poison to my family, was to me a strengthening balm.

The word went out from Ur to all the city states of Sumer. A new goddess was born: the thirteenth Anunnaki. The drums beat out from every temple.

My mother was exquisite when she was happy. She pressed the tiniest, softest kiss against the tip of my nose, and whispered: ‘All hail, Inanna.’

There was talk of taking me north. The king of the gods must see me. But my mother paced back and forth. Six days on a barge; how could it be safe for me?

As they talked, I lay on my back in my cot, stretching out my feet, and looking up and out at a square of clean spring sky. Without warning the square was full of swifts. I must have made a noise at this extraordinary sight, at this waxing and waning of what had only been flat colour. I was not upset: I was amazed. But at once my mother picked me up and cradled me against her collarbone. ‘She is too young to travel,’ she said.

Seven days went by, and then a sailing boat appeared on the horizon, leaning over hard in the wind that came in off the ocean. It was a skiff from the White Temple. The punishment for delaying such a skiff was death, and this one had come south down the river in two days and two nights, sweeping away all records before it.

Four men in black stepped off the skiff onto the marble quay at Ur, and a small object, wrapped in black linen, was handed to my mother’s chief priestess. This package was carried up through the griffin gates of Ur, and along beside the ponds and palms of the temple precinct, and then down long palace corridors, to be handed to my father as he stood beside my cradle.

Inside the linen was a small clay tablet, raw orange in colour and criss-crossed with neat flecks. My father read it slowly.

‘He is coming south,’ he said.

An, first amongst the Anunnaki, had not left his citadel since time out of mind. But now he was coming south to see me, with the lifegiving river surging beneath his barge.

It was an honour of the ages.

The farmers stood in the fields, open mouthed, to watch An’s fleet slide by.

My mother said it was too windy for me to be taken outside. But I felt An’s foot meet the marble of the quay, as he was helped from his barge. I felt him drawing closer, as he was carried through the walls of Ur, and set down at the door of the Palace of Light. I felt his slow and heavy tread along the corridors.

A muted disturbance outside our rooms, and An was with us.

The king of the Anunnaki embraced my father, and kissed my mother’s curls, and then he came over to my cradle, blacking out my square of sky. As he put one heavy hand on my chest, I burst out with a noise, an animal bleat of fear.

My mother moved as if to pick me up, but my father touched her shoulder and instead she took a step back.

I lay quiet after that, with An’s hand upon me, and the two of us looking upon each other, him so old, and me so new. He pushed his hand down on me a little heavier, smiling as he did it, but he could not make me bleat again.

‘She’s strong,’ he said, his eyes on me, ‘but strange too.’

My father came closer. ‘I see the Earthlight working on her,’ he said. ‘Changing her.’

‘I cannot feed her,’ my mother said. ‘But she is greedy for human milk.’

At this I stirred beneath An’s hand, turning my head in hope of my nurse.

‘A child of two realms,’ An said. ‘Two realms, and two peoples.’ He paused a moment and then he said: ‘What did you do, to have her?’

He was looking at me, but behind him, my mother became entirely still, a statue carved from soft flesh.

‘What do you mean, grandfather?’ she said, her voice very natural. ‘We only did the rites in temple, as we always do.’

‘We have been in this realm for four hundred years, and produced no Anunnaki babies,’ An said. ‘We make mortal babies, and half gods, and babies we cannot find names for. But never an Anunnaki. And now suddenly here one is.’

‘We did nothing that we have not always done,’ my father said, most earnest.

An touched my cheek, pressing one hot finger into my skin. ‘Well, it is done now, whatever you did,’ he said. ‘And she is Anunnaki, there is no doubt of that. We will call her the goddess of love.’

Then he leant down, his beard scratching my cheek. ‘Love and war,’ he whispered. ‘Do not forget the second part.’ The acrid smell of him filled my lungs: the stink of illness, and unimaginable old age.

‘What does a goddess of love do?’ my father asked.

An shrugged. ‘We will think of something.’

He sat down heavily in the chair next to my cradle. ‘There are stories about her already. They say she is going to be a great goddess. Queen of Heaven and Earth. Greater even than me.’

‘Do we not control the stories?’ my father said.

‘Stories are sly things,’ An said. ‘They can be hard to catch and kill.’

Excerpt from Inanna by Emily H. Wilson reprinted by permission of Titan Books.

Emily H. Wilson’s Inanna will be released August 1, 2023; you can pre-order a copy here.

Want more Gizmodo news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel and Star Wars releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about House of the Dragon and Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power.