Fantasy author Holly Black (The Spiderwick Chronicles) kicks off a new duology set in the same world as her mega-popular Folk of the Air series with January’s The Stolen Heir. Gizmodo is excited to share the first chapter of this highly anticipated YA release, so let’s get into it!

First, here’s a summary of the story to set the scene.

A runaway queen. A reluctant prince. And a quest that may destroy them both.

Eight years have passed since the Battle of the Serpent. But in the icy north, Lady Nore of the Court of Teeth has reclaimed the Ice Needle Citadel. There, she is using an ancient relic to create monsters of stick and snow who will do her bidding and exact her revenge.

Suren, child queen of the Court of Teeth, and the one person with power over her mother, fled to the human world. There, she lives feral in the woods. Lonely, and still haunted by the merciless torments she endured in the Court of Teeth, she bides her time by releasing mortals from foolish bargains. She believes herself forgotten until the storm hag, Bogdana chases her through the night streets. Suren is saved by none other than Prince Oak, heir to Elfhame, to whom she was once promised in marriage and who she has resented for years.

Now seventeen, Oak is charming, beautiful, and manipulative. He’s on a mission that will lead him into the north, and he wants Suren’s help. But if she agrees, it will mean guarding her heart against the boy she once knew and a prince she cannot trust, as well as confronting all the horrors she thought she left behind.

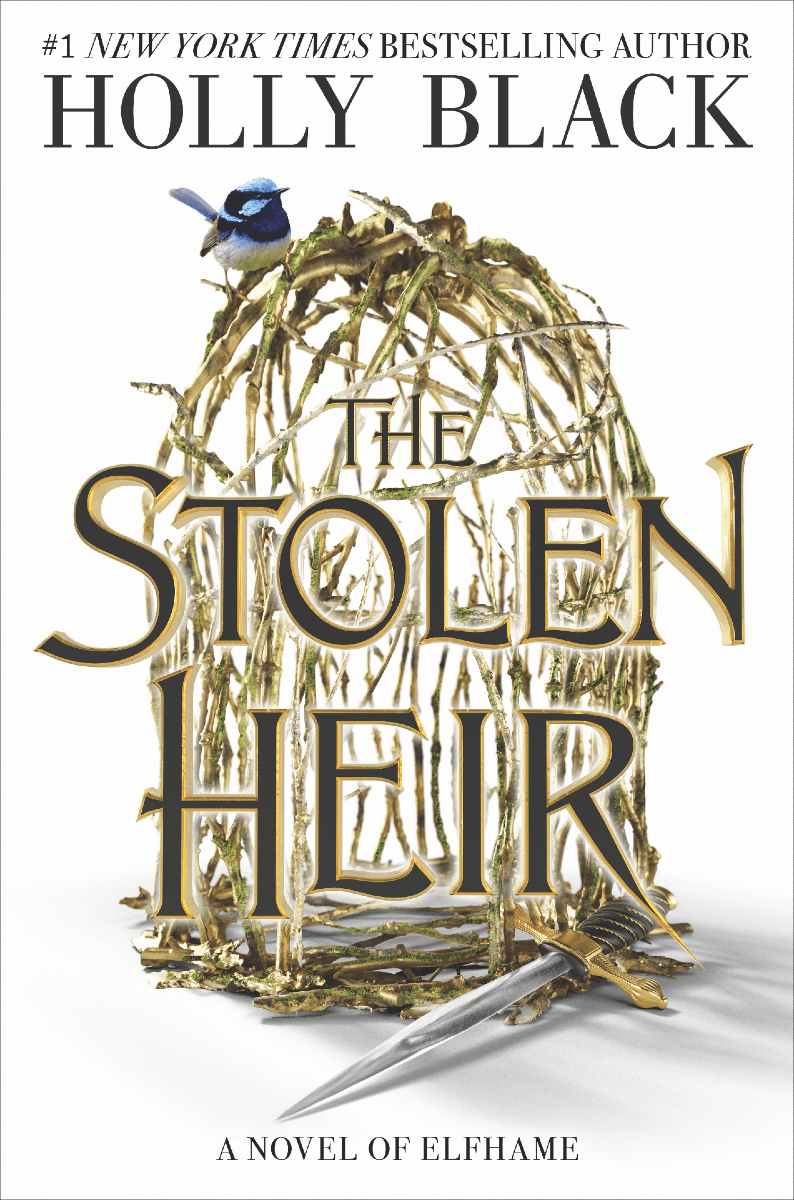

Here’s the full cover, followed by the first chapter of The Stolen Heir.

The slant of the moon tells me that it’s half past ten when my unsister comes out the back door. She’s in her second year of college and keeps odd hours. As I watch from the shadows, she sets down an empty cereal bowl on the top step of the splintery and sagging deck. Then she glugs milk into it from a carton. Spills a little. Squatting, she frowns out toward the tree line.

For an impossible moment, it’s as though she’s looking at me.

I draw deeper into the dark.

The scent of pine needles is heavy in the air, mingling with leaf mould and the moss I crush between my bare toes. The breeze carries the smell of the sticky, rotten, sugary dregs still clinging to bottles in the recycling bin; the putrid something at the bottom of the empty garbage can; the chemical sweetness of the perfume my unsister is wearing.

I watch her hungrily. Bex leaves the milk for a neighbourhood cat, but I like to pretend it’s me she’s leaving it for. Her forgotten sister.

She stands there for a few minutes while moths flit above her head and mosquitoes buzz. Only when she goes back inside do I slink closer to the house, peering through the window to watch my unmother knit in front of the television. Watching my unfather in the breakfast nook with his laptop, answering email. He puts a hand to his eyes, as though tired.

In the Court of Teeth, I was punished if I called the humans who raised me my mother and father. Humans are animals, Lord Jarel would say, the admonishment coming with a breathtakingly hard blow. Filthy animals. You share no blood with them.

I taught myself to call them unmother and unfather, hoping to avoid Lord Jarel’s wrath. I keep the habit to remind myself of what they were to me, and what they will never be again. Remind myself that there is nowhere that I belong and no one to whom I belong.

The hair on the back of my neck prickles. When I look around, I note an owl on a high branch, observing me with a swivel of its head. No, not an owl.

I pick up a rock, hurling it at the creature.

It shifts into the shape of a hob and takes off into the sky with a screech, beating feathered wings. It circles twice and then glides off toward the moon.

The local Folk are no friends to me. I’ve seen to that.

Another reason I am no one, of nowhere.

Resisting the temptation to linger longer near the backyard where I once played, I head for the branches of a hawthorn at the edge of town. I stick to the dimness of shadowed woodland, my bare feet finding their way through the night. At the entrance to the graveyard, I stop.

Huge and covered in the white blooms of early spring, the hawthorn towers over headstones and other grave markers. Desperate locals, teenagers especially, come here and tie wishes to the branches.

I heard the stories as a kid. It’s called the Devil’s Tree. Come back three times, make three wishes, and the devil was supposed to appear. He’d give you what you asked for and take what he wanted in return.

It’s not a devil, though. Now that I have lived among the Folk, I know the creature that fulfils those bargains is a glaistig, a faerie with goat feet and a taste for human blood.

I climb into a cradle of branches and wait, petals falling around me with the sway of the tree limbs. I lean my cheek against the rough bark, listening to the susurration of leaves. In the cemetery that surrounds the hawthorn, the nearby graves are more than a hundred years old. These stones have weathered thin and bone pale. No one visits them anymore, making this a perfect spot for desperate people to come and not be seen.

A few stars wink down at me through the canopy of flowers. In the Court of Teeth, there was a nisse who made charts of the sky, looking for the most propitious dates for torture and murder and betrayal.

I stare up, but whatever riddle is in the stars, I can’t read it. My education in Faerie was poor, my human education, inconsistent.

The glaistig arrives a little after midnight, clopping along. She is dressed in a long burgundy coat that stops at the knees, designed to highlight her goat feet. Her bark‑brown hair is pulled up and back into a tight braid.

Beside her flies a sprite with grasshopper‑green skin and wings to match. It’s only a bit larger than a hummingbird, buzzing through the air restlessly.

The glaistig turns to the winged faerie. “The Prince of Elfhame? How interesting to have royalty so close by…”

My heart thuds dully at prince.

“Spoiled, they say,” the sprite chirps. “And wild. Far too irresponsible for a throne.”

That doesn’t sound like the boy I knew, but in the four years since I saw him last, he would have been inducted into all the pleasures of the High Court, would have been served up a surfeit of every imaginable debauched delight. Sycophants and toadies would be so busy vying for his attention that, these days, I wouldn’t be allowed close enough to kiss the hem of his cloak.

The sprite departs, darting up and away, thankfully not weaving through the branches of the tree where I crouch. I settle in to observe.

Three people come that night to make wishes. One, a sandy‑haired young man I went to fourth grade with, the year before I was taken. His fingers tremble as he ties his scrap of paper to the branch with a bit of twine. The second, an elderly woman with a stooped back. She keeps wiping at her wet eyes, and her note is tearstained by the time she affixes it with a twist tie. The third is a freckled man, broad‑shouldered, a baseball cap pulled low enough to hide most of his face.

This is the freckled man’s third trip, and at his arrival, the glaistig steps out of the shadows. The man gives a moan of fear. He didn’t expect this to be real. They seldom do. They embarrass themselves with their reactions, their terror, the sounds they make.

The glaistig makes him tell her what he wants, even though he’s written it three separate times on three separate notes. I don’t think she ever bothers to read the wishes.

I do. This man needs money because of some bad business deal. If he doesn’t get it, he will lose his house, and then his wife will leave him. He whispers this to the glaistig, fidgeting with his wedding ring as he does so. In return, she gives him her terms — every night for seven months and seven days, he must bring her a cube of fresh human flesh. He may cut it from himself, or from another, whichever he prefers.

He agrees eagerly, desperately, foolishly, and lets her tie an ensorcelled piece of leather around his wrist.

“This was crafted from my own skin,” she tells him. “It will let me find you, no matter how you try to hide from me. No mortal‑made knife can cut it, and should you fail to do as you have promised, it will tighten until it slices through the veins of your arm.”

For the first time, I see panic on his face, the sort that he ought to have felt all along. Too late, and part of him knows it. But he denies it a moment later, the knowledge surfacing and being shoved back down.

Some things seem too terrible to seem possible. Soon he may learn that the worst thing he can imagine is only the beginning of what they are willing to do to him. I recall that realisation and hope I can spare him it.

Then the glaistig tells the freckled man to gather leaves. For each one in his pile, he’ll get a crisp twenty‑dollar bill in its place. He’ll have three days to spend the money before it disappears.

In the note he attached to the tree, he wrote that he needed $US40,000 ($55,528). That’s two thousand leaves. The man scrambles to get together a big enough pile, searching desperately through the well‑manicured graveyard. He collects some from the stretch of woods along the border and rips handfuls from a few trees with low‑hanging branches. Staring at what he assembles, I think of the game they have at fairs, where you guess the number of jelly beans in a jar.

I wasn’t good at that game, and I worry he isn’t, either.

The glaistig glamours the leaves into money with a bored wave of her hand. Then he’s busy stuffing the bills into his pockets. He races after a few the wind takes and whips toward the road.

This seems to amuse the glaistig, but she’s wise enough not to hang around to laugh. Better he not realise how thoroughly he’s been had. She disappears into the night, drawing her magic to shroud her.

When the man has filled his pockets, he shoves more bills into his shirt, where they settle against his stomach, forming an artificial paunch. As he walks out of the graveyard, I let myself drop silently out of the tree.

I follow him for several blocks, until I see my chance to speed up and grab hold of his wrist. At the sight of me, he screams.

Screams, just like my unmother and unfather.

I flinch at the sound, but the reaction shouldn’t surprise me. I know what I look like.

My skin, the pale blue of a corpse. My dress, streaked with moss and mud. My teeth, built for ease of ripping flesh from bone. My ears are pointed, too, hidden beneath matted, dirty blue hair, only slightly darker than my skin. I am no pixie with pretty moth wings. No member of the Gentry, whose beauty makes mortals foolish with desire. Not even a glaistig, who barely needed a glamour if her skirts were long enough.

He tries to pull away, but I am very strong. My sharp teeth make short work of the glaistig’s string and her spell. I’ve never learned to glamour myself well, but in the Court of Teeth I grew skilled at breaking curses. I’d had enough put on me for it to be necessary.

I press a note into the freckled man’s hands. The paper is his own, with his wish written on one side. Take your family and run, I wrote with one of Bex’s Sharpies. Before you hurt them. And you will.

He stares after me as I race off, as though I am the monster.

I have seen this particular bargain play out before. Everyone starts out telling themselves that they will pay with their own skin. But seven months and seven days is a long time, and a cube of flesh is a lot to cut from your own body every night. The pain is intense, worse with each new injury. Soon it’s easy to justify slicing a bit from those around you. After all, didn’t you do this for their sake? From there, things go downhill fast.

I shudder, remembering my own unfamily looking at me in horror and disgust. People who I believed would always love me. It took me the better part of a year to discover that Lord Jarel had enchanted their love away, that his spells were the reason he was so certain they wouldn’t want me.

Even now, I do not know if the enchantment is still on them.

Nor do I know whether Lord Jarel amplified and exploited their actual horror at the sight of me or created that feeling entirely out of magic.

It is my revenge on Faerie to unravel the glaistig’s spells, to undo every curse I discover. Free anyone who is ensnared. It doesn’t matter if the man appreciates what I’ve done. My satisfaction comes at the glaistig’s frustration at another human slipping from her net.

I cannot help them all. I cannot prevent them from taking what she offers and paying her price. And the glaistig is hardly the only faerie offering bargains. But I try.

By the time I return to my childhood home, my unfamily has all gone to bed.

I lift the latch and creep through the house. My eyes see well enough in the dark for me to move through the unlit rooms. I go to the couch and press my unmother’s half‑finished sweater to my cheek, feeling the softness of the wool, breathing in the familiar scent of her. Think of her voice, singing to me as she sat at the end of my bed.

Twinkle, twinkle, little star.

I open the garbage and pick out the remains of their dinner. Bits of gristly steak and gobs of mashed potatoes clump together with scattered pieces of what must have been a salad. It’s all mixed in with crumpled‑up tissues, plastic wrap, and vegetable peels. I make a dessert of a plum that’s mushy on one end and the little bit of jam at the bottom of a jar in the recycling bin.

I gobble the food, trying to imagine that I am sitting at the table with them. Trying to imagine myself as their daughter again, and not what’s left of her.

A cuckoo trying to fit back into the egg.

Other humans sensed the wrongness in me as soon as I set foot in the mortal world. That was right after the Battle of the Serpent, when the Court of Teeth had been disbanded and Lady Nore fled. With nowhere else to go, I came here. That first night back, I was discovered by a handful of children in a park who picked up sticks to drive me off. When one of the bigger ones jabbed me, I ran at him, sinking my sharp teeth into the meat of his arm. I opened up his flesh as though he were a tin can.

I do not know what I would do to my unfamily if they pushed me away again. I am no safe thing now. A child no more, but a fully grown monster, like the ones that came for me.

Still, I am tempted to try to break the spell, to reveal myself to them. I am always tempted. But when I think of speaking with my unfamily, I think of the storm hag. Twice, she found me in the woods outside the human town, and twice she hung the strung‑up and skinned body of a mortal over my camp. One who she claimed knew too much about the Folk. I don’t want to give her a reason to choose one of my unfamily as her next victim.

Upstairs, a door opens and I freeze. I fold up my legs, circling my arms around my knees, trying to make myself as small as possible. A few minutes later, I hear a toilet flush and let myself breathe normally again.

I shouldn’t come. I don’t always — some nights, I manage to stay far away, eating moss and bugs and drinking from dirty streams. Going through the dumpsters behind restaurants. Breaking spells so that I can believe I’m not like the rest of them.

But I am lured back, again and again. Sometimes I wash the dishes in the sink or move wet clothes to the dryer, like a brownie. Sometimes I steal knives. When I am at my angriest, I rip a few of their things into tiny shreds. Sometimes I doze behind the couch until they all leave for work or school and I can crawl out again. Search through the rooms for scraps of myself, report cards and yarn crafts. Family photos that include a human version of me with my pale hair and pointy chin, my big, hungry eyes. Evidence that my memories are real. In one box marked Rebecca, I found my old stuffed fox and wonder how they explained away an entire room of my belongings.

Rebecca goes by Bex now, a new name for her fresh start in college. Despite her probably telling everyone who asks that she’s an only child, she’s in nearly every good memory I have of being a kid. Bex drinking cocoa in front of the television, squishing marshmallows until her fingers were sticky. Bex and I kicking each other’s legs in the car until Mum yelled at us to stop. Bex sitting in her closet, playing action figures with me, holding up Batman to kiss Iron Man and saying: Let’s get them married, and then they can get some cats and live happily ever after. Imagining myself scrubbed out of those memories makes me grind my teeth and feel even more like a ghost.

Had I grown up in the mortal world, I might be in school with Bex. Or travelling, taking odd jobs, discovering new things. That Wren would take her place in the world for granted, but I can no longer imagine my way into her skin.

Sometimes I sit up on the roof, watching the bats twirl in the moonlight. Or I watch my unfamily sleep, reaching my hand daringly close to my unmother’s hair. But tonight, I only eat.

When I am done with the scavenged meal, I go to the sink and stick my head underneath the tap, guzzling the sweet, clear water. After I have my fill, I wipe my mouth with the back of my hand and slip out onto the deck. At the top step, I drink the milk my unsister put out. A bug has fallen in and spins on the surface. I drink that, too.

I am about to slink back into the woods when a long shadow comes from the side yard, its fingers like branches.

Heart racing, I pad down the steps and slide beneath the porch. I make it just moments before Bogdana lopes around the corner of the house. She is every bit as tall and terrifying as I remember her being that first night, and worse, because now I know of what she is capable.

My breath catches. I have to bite down hard on the inside of my cheek to keep quiet and still.

I watch Bogdana drag one of her nails across the sagging aluminium siding. Her fingers are as long as flower stalks, her limbs as spindly as sticks of birch. Weed‑like strands of black straight hair hang over her mushroom‑pale face, half‑hiding tiny eyes that gleam with malice.

She peers in through the glass panes of a window. How easy to push up a sash, to creep in and slit the throats of my unfamily as they sleep, then flense the skins from their bodies.

My fault. If I had been able to stay away, she wouldn’t have scented my spoor here. Wouldn’t have come. My fault.

And now I have two choices. I can stay where I am and listen to them die. Or I can lead her from the house. It’s no choice at all, except for the fear that has been my constant companion since I was stolen from the mortal world. Terror seared deep in my marrow.

Deeper than my desire to be safe, though, I want my unfamily to live. Even if I no longer belong with them, I need to save them. Were they gone, the last shred of what I was would be gone with them, and I would be set adrift.

Taking a deep, shuddery breath, I kick out from underneath the porch. I run for the road, away from the cover of woods, where she would easily gain on me. I am heedless in my steps across the lawn, ignoring the snapping of twigs beneath my bare feet. The crack of each one carries through the night air.

I do not look back, but I know that Bogdana must have heard me. She must have turned, nostrils flaring, scenting the breeze. Movement draws the eye of the predator. The instinct to chase.

I wince against the headlights of the cars as I hit the footpath.

Leaves are tangled into the muddy clots of my hair. My dress — once white — is now a dull and stained colour, like the gown one would expect to adorn a ghost. I do not know if my eyes shine like an animal’s. I suspect they might.

The storm hag sweeps after me, swift as a crow and certain as doom.

I pump my legs faster.

Sharp bits of gravel and glass dig into my feet. I wince and stumble a little, imagining I can feel the breath of the hag. Terror gives me the strength to shoot forward.

Now that I have drawn her off, I must lose her somehow. If she becomes distracted for even a moment, I can slip away and hide. I got very good at hiding, back at the Court of Teeth.

I turn into an alley. There’s a gap in the chain‑link fence at the end, small enough for me to wriggle through. I run for it, feet sliding in muck and trash. I hit the fence and press my body into the opening, metal scratching my skin, the stink of iron heavy in the air.

As I race on, I hear the shake of the fence as it’s being climbed.

“Stop, you little fool!” the storm hag shouts after me.

Panic steals my thoughts. Bogdana is too fast, too sure. She’s been killing mortals and faeries alike since long before I was born. If she summons lightning, I’m as good as dead.

Instinct makes me want to go to my part of the woods. To burrow in the cave‑like dome I’ve woven from willow branches. Lie on my floor of smooth river stones, pressed down into the mud after a rainstorm until they made a surface flat enough to sleep on. Cocoon myself in my three blankets, despite them being moth‑eaten, stained, and singed by fire along a corner.

There, I have a carving knife. It is only as long as one of her fingers, but sharp. Better than either of the other little blades I have on my person.

I dart sideways, toward an apartment complex, running through the pools of light. I cut across streets, through the playground, the creak of swing chains loud in my ears.

I have more skill at unravelling enchantments than making them, but since her last visit I warded around my lair so that a dread comes upon anyone who gets too close. Mortals stay away from the place, and even the Folk become uneasy when they come near.

I have little hope that will chase her off, but I have little hope at all.

Bogdana was the one person that Lord Jarel and Lady Nore feared. A hag who could bring on storms, who had lived for countless scores of years, who knew more of magic than most beings alive. I saw her slash open and devour humans in the Court of Teeth and gut a faerie with those long fingers over a perceived insult. I saw lightning flash at her annoyance. It was Bogdana who helped Lord Jarel and Lady Nore with their scheme to conceive a child and hide me away among mortals, and many times she had been witness to my torment in the Court of Teeth.

Lord Jarel and Lady Nore never let me forget that I belonged to them, despite my title as queen. Lord Jarel delighted in leashing me and dragging me around like an animal. Lady Nore punished me ferociously for any imagined slight, until I became a snarling beast, clawing and biting, barely aware of anything but pain.

Once, Lady Nore threw me out into the howling wasteland of snow and barred the castle doors against me.

If being a queen doesn’t suit you, worthless child, then find your own fortune, she said.

I walked for days. There was nothing to eat but ice, and I could hear nothing but the cold wind blowing around me. When I wept, the tears froze on my cheeks. But I kept on going, hoping against hope that I might find someone to help me or some way to escape. On the seventh day, I discovered I had only gone in a great circle.

It was Bogdana who wrapped me in a cloak and carried me inside after I collapsed in the snow.

The hag carried me to my room, with its walls of ice, and set me down on the skins of my bed. She touched my brow with fingers twice as long as fingers ought to be. Looked down at me with her black eyes, shook her head of wild, storm‑tossed hair. “You will not always be so small or so frightened,” she told me. “You are a queen.”

The way the hag said those words made me raise my head. She made the title sound as though it was something of which I ought to be proud.

When the Court of Teeth ventured south, to war with Elfhame, Bogdana did not come with us. I thought to never see her again and was sorry for it. If there was one of them who might have looked out for me, it was her.

Somehow that makes it worse that she’s the one at my heels, the one hunting me through the streets.

When I hear the hag’s footfalls draw close, I grit my teeth and try for a burst of speed. My lungs are already aching, my muscles sore.

Perhaps, I try to tell myself, perhaps I can reason with her. Perhaps she is chasing me only because I ran.

I make the mistake of glancing back and lose the rhythm of my stride. I falter as the hag reaches out a long hand toward me, her knife‑ sharp nails ready to slice.

No, I don’t think I can reason with her.

There is only one thing left to do, and so I do it, whirling around. I snap my teeth in the air, recalling sinking them into flesh. Remembering how good it felt to hurt someone who scared me.

I am not stronger than Bogdana. I am neither faster nor more cunning. But it’s possible I am more desperate. I want to live.

The hag draws up short. At my expression, she takes a step toward me, and I hiss. There is something in her face, glittering in her black eyes, that I do not understand. It looks triumphant. I reach for one of the little blades beneath my dress, wishing again for the carving knife.

The one I pull out is folded, and I fumble trying to open it.

I hear the clop of a pair of hooves, and I think that somehow it is the glaistig, come to watch me be taken. Come to gloat. She must have been the one to alert Bogdana to what I was doing; she must be the reason this is happening.

But it is not the glaistig who emerges from the darkness of the woods. A young man with goat feet and horns, wearing a shirt of golden scale mail and holding a thin‑bladed rapier, steps into the pool of light near a building. His face is expressionless, like someone in a dream.

I note the curls of his tawny blond hair tucked behind his pointed ears, the garnet‑coloured cloak tossed over wide shoulders, the scar along one side of his throat, a circlet at his brow. He moves as though he expects the world to bend to his will.

Above us, clouds are gathering. He points his sword toward Bogdana.

Then his gaze flickers to me. “You’ve led us on a merry chase.” His amber eyes are bright, like those of a fox, but there is nothing warm in them.

I could have told him not to look away from Bogdana. The hag sees the opening and goes for him, nails poised to rip open his chest.

Another sword stops her before he needs to parry. This one is held in the gloved hand of a knight. He wears armour of sculpted brown leather banded with wide strips of a silvery metal. His blackberry hair is cropped short, and his dark eyes are wary.

“Storm hag,” he says.

“Out of my way, lapdog,” she tells the knight. “Or I will call down lightning to strike you where you stand.”

“You may command the sky,” the horned man in the golden scale mail returns. “But, alas, we are here on the ground. Leave, or my friend will run you through before you summon so much as a drizzle.”

Bogdana narrows her eyes and turns toward me. “I will come for you again, child,” she says. “And when I do, you best not run.”

Then she moves into the shadows. As soon as she does, I try to dash to one side of him, intent on escape.

The horned man seizes hold of my arm. He’s stronger than I expect him to be.

“Lady Suren,” he says.

I growl deep in my throat and catch him with my nails, raking them down his cheek. Mine are nowhere near as long or sharp as Bogdana’s, but he still bleeds.

He makes a hiss of pain but doesn’t let go. Instead, he wrenches my wrists behind my back and holds them tight, no matter how I snarl or kick. Worse, the light hits his face at a different angle and I finally recognise whose skin is under my fingernails.

Prince Oak, heir to Elfhame. Son of the traitorous Grand General and brother to the mortal High Queen. Oak, to whom I was once promised in marriage. Who had once been my friend, although he doesn’t seem to remember it.

What was it the pixie had said about him? Spoiled, irresponsible, and wild. I believe it. Despite his gleaming armour, he is so poorly trained in swordplay that he didn’t even attempt to block my blow.

But after that thought comes another one: I have struck the Prince of Elfhame.

Oh, I am in trouble now.

“Things will be much easier if you do exactly as we tell you from this moment forward, daughter of traitors,” the dark‑eyed knight in the leather armour informs me. He has a long nose and the look of someone more comfortable saluting than smiling.

I open my mouth to ask what they want with me, but my voice is rough with disuse. The words come out garbled, the sounds not the ones I intended.

“What’s the matter with her?” he asks, frowning at me as though I am some sort of insect.

“Living wild, I suppose,” says the prince. “Away from people.”

“Didn’t she at least talk to herself?” the knight asks, raising his eyebrows.

I growl again.

Oak brings his fingers to the side of his face and draws them back with a wince. He has three long slashes there, bleeding sluggishly.

When his gaze returns to me, there’s something in his expression that reminds me of his father, Madoc, who was never so happy as when he went to war.

“I told you that nothing good ever came out of the Court of Teeth,” says the knight, shaking his head. Then he takes a rope and ties it around my wrists, looping it through the middle to make it secure. He doesn’t pierce my skin like Lord Jarel used to, leashing me by stabbing a needle threaded with a silver chain between the bones of my arms. I am not yet in pain.

But I do not doubt that I will be.

Excerpt from Holly Black’s The Stolen Heir reprinted by permission of Little, Brown Books for Young Readers.

The Stolen Heir by Holly Black will be released January 3; you can pre-order a copy here and keep up to date on its release through the publisher’s NOVL enewsletter.

Want more Gizmodo news? Check out when to expect the latest Marvel, Star Wars, and Star Trek releases, what’s next for the DC Universe on film and TV, and everything you need to know about James Cameron’s Avatar: The Way of Water.