It’s that time of year again in climate world, when everyone starts packing their bags and sending emails and writing news articles about a process that is completely and totally incomprehensible to most normal people: the Conference of Parties, or COP. It’s frustrating, boring, and dominated by corporate interests, but it is unfortunately the one mechanism that we have to putt global effort behind curbing climate change.

Last year, Earther reported live from Glasgow for the last COP, where we witnessed the highs and lows of international climate negotiations (and ate some dope vegan haggis). We’re staying home this year, but we’ve put together a primer for what to watch — and why you should care.

What is COP27 and what does it stand for?

It’s the 27th annual UN Climate Change Conference. It’s short for the Conference of Parties 27.

When and where is COP27?

It begins on November 6 and continues until November 18 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt.

What is a COP, anyway?

COP stands for Conference of Parties. It’s the UN term for the yearly talks to discuss climate change and the implementation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, a treaty signed in 1994 that dictates, in essence, that the world needs to get its act together to stop runaway warming.

Once a year, UN delegates and representatives from the countries in the treaty, as well as a handful of nonprofit, business, and other interests — known as “civil society” — gather together to hammer out details on how the world is going to fix the mess we’ve made. This COP marks the 27th time that this meeting has happened.

In 2015, at a COP in Paris, the world came together to sign the Paris Agreement, which stated that countries would try to avoid, at maximum, 2 degrees Celsius of additional warming by the end of this century, with an aspirational target of avoiding 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming. The post-Paris meetings now focus on the implementation of this agreement.

For more on the history of COP, check out our explainer from last year.

What happened last year?

As the clock ticked down at the end of the 2021 conference in Scotland, world powers managed to come together to sign what’s known as the Glasgow Climate Pact to agree on several important steps moving forward in the implementation of the Paris Agreement. The pact marked a historic moment, with countries for the first time agreeing to phase out fossil fuel use — a huge deal in the context of the history of COPs.

However, the text itself left a lot of loopholes, and all told, it’s a pretty small step forward in terms of what we know needs to be done on climate change. What’s more, the text around fossil fuels was actually watered down by powerful countries unwilling to significantly ease up on fossil fuel use (including the U.S.).

There were a lot of people pissed about the outcome of last year’s talks, the lack of progress on issues facing developing nations hard-hit by climate change, and how the text of the Glasgow Pact seemed to leave a lot of space for polluters to keep on pollutin’. The talks last year also left some huge issues on the table, which will now bleed over into this year.

What is going to happen this year?

While last year’s meeting ended in several important conclusions and agreements, this year is what’s known as a technical COP — it’s a meeting that’s focused on hammering out the details of how to actually make the changes world powers have agreed to.

“Some aspects of the international negotiations are focused on procedural and implementation details, which are important to get right and piggyback on existing agreements,” Rachel Cleetus, a policy director at the Union of Concerned Scientists, told Earther in an email. “Others are focused on forging new agreements on issues of importance that may be challenging but require attention.”

That doesn’t mean that important stuff isn’t still on the table, however — especially for developing nations.

“This COP has been billed as the ‘Africa COP,’” Cleetus explained, referring to the meeting’s location in Egypt, “but that moniker will ring hollow if it fails to prioritise issues of urgent importance to African nations, including addressing climate loss and damage, harnessing climate finance from richer nations to foster a clean energy transition and close the energy poverty gap on the continent, and ensuring major emitters raise the ambition of their emission reduction pledges.”

What are some of the big issues?

Thanks to the lack of progress made on several key areas in Glasgow, there’s a lot on the table this year.

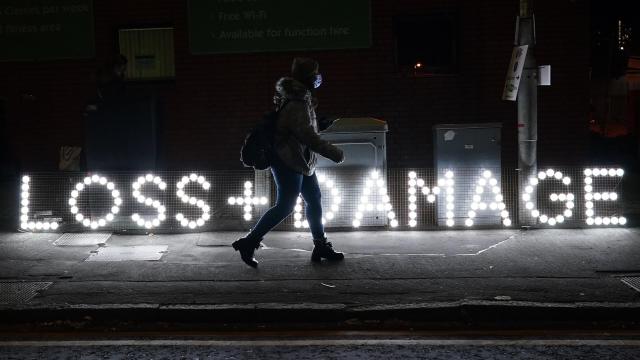

Loss and Damage

This term refers to the irreversible and devastating changes — cultural, financial, political — that climate change is having on developing countries that had little to do with contributing to historic emissions. In the context of COP, the term “loss and damage” usually refers to figuring out protocols for helping these countries financially; the topic has been a sticking point for a long time in international climate negotiations. The Paris Agreement mandates that countries address and minimise loss and damage, but figuring out how that mechanism actually works is another story entirely.

“Last year, at COP26 in Glasgow, the United States and other rich nations blocked a pathway to funding to address climate loss and damage that many low- and middle-income countries were demanding, and instead just allowed for a dialogue on it,” Cleetus said. “It’s now past time for rich nations to acknowledge the terrible, unjust burden they are imposing on communities in low-income, climate vulnerable countries and fully own their responsibility to address the problem. That includes a clear, near-term pathway to funding to address loss and damage. Additionally, a human rights-centered approach to meeting the needs of people forcibly displaced by climate change is also needed.”

Raising Emissions Reductions Goals

You may have heard: We don’t have a lot of time to figure a lot of this stuff out. Under the Paris Agreement, countries are supposed to ratchet up their goals for reducing emissions every couple of years — the goals everyone has put on the table are merely a starting point. In Glasgow last year, countries agreed to submit their increased nationally determined contributions, or NDCs, by the end of 2022; as of early November, just a handful of countries had.

“There is still much we can do to bend that emissions curve sharply within this decade — but only if world leaders, especially leaders of richer countries and major emitting nations, take responsibility to act together quickly and fossil fuel companies are held accountable for their decades of obstruction and deception,” Cleetus said.

Climate Finance

Richer countries have made promises to poorer ones to help them out financially but haven’t followed through on those agreements. In 2009, the world’s top economies agreed to pay $US100 ($139) billion each year to developing nations by 2020; they’ve thus far failed to meet that deadline. While wealthy countries put together a roadmap last year to provide $US100 ($139) billion by 2023, some nations hard-hit by climate change say more finance is now needed. The question of how to meet — and how to exceed — this $US100 ($139) billion target will absolutely be on the agenda in Egypt.

What might happen? What’s in the way of progress?

In an ideal world, countries at this meeting — especially the wealthy, powerful ones — would heed the escalating warnings about just how little time we have left and get their asses into gear. They’d put together clear pathways for funding for lower-income countries experiencing loss and damage to find relief. They’d put their nose to the grindstone and throw themselves into their commitments to keep reducing their emissions, with an eye to bringing them down as much as possible in this decade. They’d figure out a way to fulfil promises on climate finance to help all countries make the clean energy transition.

But as we saw last year in Glasgow, consensus is much easier said than done. “The roadblocks [to success at COP] include continued obstruction from richer countries to meet their responsibilities, challenges created by the ongoing global energy and economic crises, and lack of access to the COP for many civil society groups from African nations who haven’t been able to get badges or lack the resources to travel to Egypt,” Cleetus said.

Why should I care about this?

Great question. As we documented last year, COPs are weird events — both incredibly important and agonizingly slow, where much of the action happens between negotiators behind closed doors as civil society waits outside. Greta Thunberg said she won’t be going, noting that space for civil society at this COP was very limited but also calling the event “an opportunity for leaders and people in power to get attention, using many different kinds of greenwashing.”

Thunberg certainly isn’t wrong about the greenwashing: polluting sponsors and influence are everywhere at COP. Last year, the fossil fuel industry managed to send more than 500 lobbyists and other representatives to the talks, larger than some of the delegations of countries affected by climate change. (This year is no exception — Coca-Cola is once again a sponsor, despite being one of the world’s worst plastic polluters.) It’s enough to make anyone question the efficacy of the proceedings.

“Regardless of who is at COP, the onus is firmly on world leaders, especially from richer countries, to deliver a successful outcome at COP27,” Cleetus said. “Overall, whether certain individuals are there in person or not, anyone who cares about the future of our planet and cares about future generations should simply be pushing for these annual negotiations to deliver ambitious outcomes in line with the latest science and that centre equity and justice for those on the frontlines of the climate crisis. It’s also vital for climate activists from the Global South, like Vanessa Nakate and Elizabeth Wathuti to be at COP27 and have their voices elevated and amplified. They are representing communities in Africa facing dire climate impacts and calling for the solutions they need and deserve.”

Despite the molasses-slow nature of these talks and the welcoming of polluters, these meetings are desperately important: They’re the only mechanism we have right now to address climate change from a global context and to help out the countries that have been hit the hardest and are the least responsible.