In 2018, a man was arrested for stealing a pair of socks from a T.J. Maxx store in New York City, even though he was signed in at a hospital for the birth of his child when the crime was committed. The police never checked the man’s alibi, and the case rested on a single piece of evidence. Apparently, a police officer had run security footage through a facial recognition database and found a “possible match.” The officer texted a photo of the man to a witness who said “that’s the guy.” After six months in jail, the man pleaded guilty, though he maintains his innocence.

Unfortunately, this story represents a growing trend, not a tragic exception. The anecdote opens a landmark report on facial recognition from the Georgetown Law Centre on Privacy & Technology, which found that law enforcement agencies are often using the technology as the sole basis for putting people in jail despite claiming they don’t and despite a growing body of evidence that the technology has serious problems with accuracy and bias.

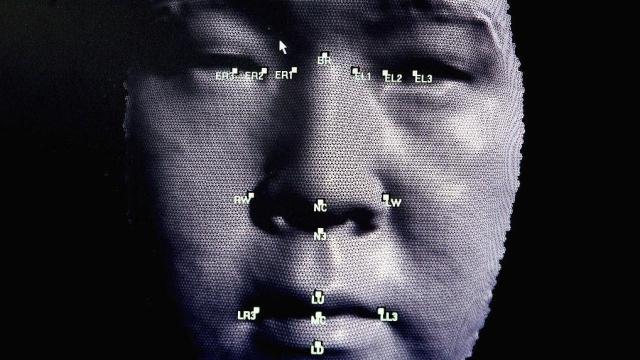

The report, titled “A Forensic Without the Science: Face Recognition in U.S. Criminal Investigations,” focuses on the technical shortcomings of facial recognition software, which are many and multiform, according to the authors.

“Police have used face recognition for more than 20 years based on the assumption that it is a reliable identification tool,” said Clare Garvie, author of the report, and a distinguished fellow with the Centre on Privacy & Technology. “Not only has that assumption never been tested, there is every reason to posit that face recognition doesn’t produce reliable leads and in fact may put people at risk of misidentification and wrongful arrest.”

Studies show that facial recognition is less accurate when tasked with identifying the faces of women and people of colour — particularly people with darker complexions. Those problems are so severe that some experts have argued it should be banned altogether.

Even under the best conditions, the people using the technology introduce their own problems. As the report puts it, “algorithms and humans may compound the other’s mistakes.” Users make false assumptions about the tech’s accuracy. And when a facial recognition scan turns out a lineup of possible suspects, the people interpreting those results are biased by facial features such as demographics and expressions.

“Over its past 20 years of use, face recognition algorithms have improved, but the people running the searches have not,” Garvie said. “Police departments are still not required to implement policies and training programs to guard against cognitive bias, misuse, and mistake.”

Law enforcement officials and companies who make facial recognition software acknowledge those issues, and often say the technology should only be used to generate leads. But investigators ignore that caution, Garvie and company found. The report highlights multiple cases where police used facial recognition evidence as probable cause to make arrests.

A key problem is there are no clear guidelines about how facial recognition technology should be used, in part because the technology is new, but also because we don’t fully understand facial recognition’s flaws. If and when those guidelines are developed, they will likely come in response to the prosecution of innocent people, they wrote.

Due to a lack of transparency, we don’t know how many people have been put in jail thanks to facial recognition, but according to the report, the number is growing. Law enforcement often fails to disclose when facial recognition is used in an investigation, which a problem for defendants in legal cases, because they can’t dispute evidence derived from flawed technology if they don’t know about it. The report argues that the results of facial recognition are so unreliable that they should be considered Brady material — a legal term for evidence that prosecutors are required to disclose because it helps defendants.

According to Garvie, failing to disclose the details about facial recognition in a criminal case violates people’s legal rights. “This is a due process violation, one that has been happening since 2001,” she said.

We’ve known about facial recognition’s problems for a long time, but law enforcement and large swaths of the public continue to put blind trust in the technology.

“There is still a tendency to place undue faith in an artificial neutral, mathematics-based approach to solving hard problems or eliminating human error from decision-making,” Garvie said. “This is the wrong approach.”