New research Friday might complicate the perception of oxytocin as the so-called “love hormone.” Scientists have found that prairie voles that were genetically bred without oxytocin receptors can still mate with others and breastfeed their children — behaviours long closely linked to the hormone. While oxytocin is still important to voles and other animals, including humans, the results suggest it’s only one of many factors that affect how we interact with others.

Oxytocin is produced by the hypothalamus and is released into the bloodstream by the pituitary gland. One of its clearest functions in humans is causing the uterus to contract during the delivery of a child, and it’s even used medically to help induce labour. Afterward, it helps regulate the production of breast milk. But it also seems to facilitate a variety of social behaviours in humans and other mammals. Studies have found that it’s often released during moments of bonding, such as between new mothers and their babies, between romantic partners during sex, and even between an owner and pet (some have even shown that both dogs and humans release oxytocin when near each other).

These findings have led to oxytocin’s nickname as the love hormone. And some scientists have even speculated that the relative lack of oxytocin might contribute to a higher risk of conditions like depression, schizophrenia, and autism. Likewise, there have been studies testing whether giving oxytocin to people with these conditions can improve their social functioning.

Much of the research on oxytocin has focused on prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster), one of the few mammal species known to form lifelong and (mostly) monogamous relationships with their mating partners. Studies have found that oxytocin, along with the hormone vasopressin, appears to play a vital role in governing these behaviours in voles. When scientists have given male voles drugs that block their ability to take in oxytocin, for instance, they started spending much less time with their partners.

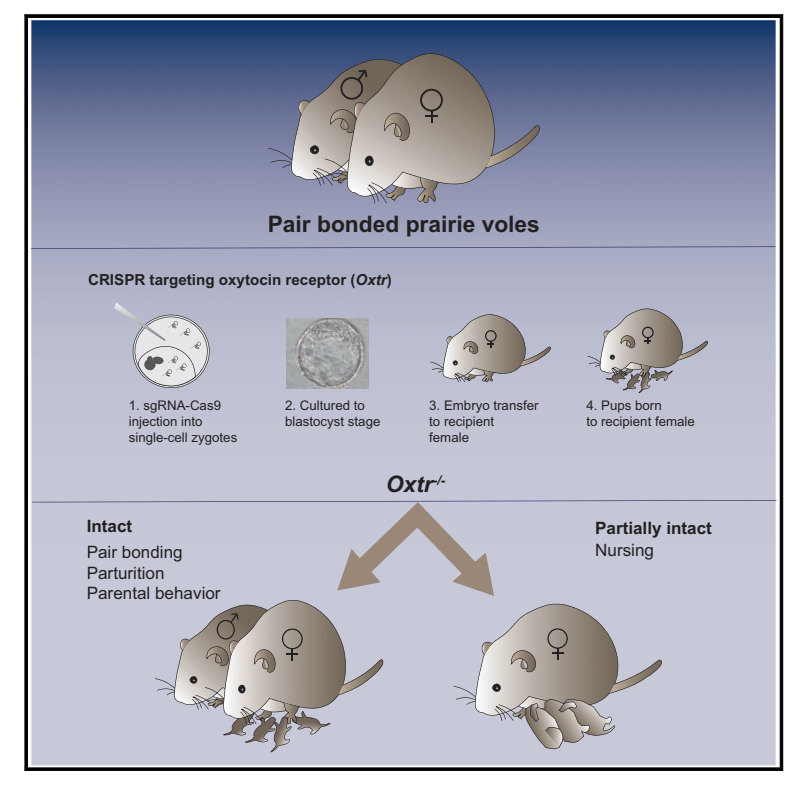

A team of researchers at Stanford University and elsewhere have long been interested in studying prairie voles, particularly as a model for better understanding social behaviour in humans. More recently, they’ve begun to develop techniques for selectively editing the genes of these animals using CRISPR, a practice commonly used for studying mice and other animals. As part of their initial tests of this technology, they decided to see what would happen if they bred voles that had their oxytocin receptors knocked out, nullifying any potential effects of the hormone on their development.

To their astonishment, the mutant voles didn’t really seem all that different, both in how they bonded to their partners and took care of their pups (a shared task for parents).

“Despite being oxytocin receptor-less, male and female voles form long-term social attachments following sexual encounters. They can also deliver pups on schedule and most surprising perhaps, they can produce enough milk so that many pups survive to weaning and beyond,” study author Nirao Shah, a professor of psychiatry, behavioural sciences, and neurobiology at Stanford, told Gizmodo in an email. “The pups that do survive however are smaller than pups born to normal mothers, indicating that the oxytocin receptor plays an important (but not essential) role in milk ejection and nursing.”

The results do conflict with past studies that tried to block oxytocin in these voles, but the differences might amount to how this was accomplished, the authors say. Drugs that can suppress the oxytocin receptor in adult voles, for instance, could possibly have other off-target effects, whereas the team’s gene editing should be more precise. It’s also possible that past a certain point in their development, oxytocin does become essential to the social behaviour of voles, so you can’t get rid of it without major consequences. But in voles that can’t process oxytocin from the very start of life, their biology might compensate in other ways to ensure healthy development.

“What the genetics reveals is that there isn’t a ‘single point of failure’ for behaviours that are so critical to the survival of the species,” Shah said.

The team’s findings, published in Neuron on Friday, aren’t the first to suggest that oxytocin’s effect on sociability isn’t so cut and dry. Trials testing whether giving people oxytocin can boost their ability to trust others have found mixed results at best, for instance. And overall, there’s no strong evidence that oxytocin doses can substantially improve people’s social functioning. At the same time, the results shouldn’t completely diminish the importance of oxytocin to both prairie voles and humans. The hormone clearly matters, but likely only as one cog of many that influences social interaction. It’s also possible that oxytocin might still have value as a treatment in certain situations.

As for the researchers, their work now leaves them with a new puzzle to solve.

“The key question for us is: if it’s not the oxytocin receptor, then what are the central players (hormones and their receptors) that lead to the formation of social attachment,” and an adequate ability to breastfeed in prairie voles, Shah said. Finding the answers to that question might someday lead to new treatments for humans, or at least a better understanding of our social behaviours.