Nearly 200 years after Ludwig van Beethoven died, a team of researchers has managed to sequence the German composer’s genome from locks of his hair, revealing surprising details of his health and genealogical history.

Chief among them: Beethoven had inherited genetic risk factors for liver diseases and was infected with hepatitis B; taken alongside the composer’s alcohol consumption, these likely contributed to his death at age 56. The team’s research is published today in Current Biology.

“Our primary goal was to shed light on Beethoven’s health problems, which famously include progressive hearing loss, beginning in his mid- to late-20s and eventually leading to him being functionally deaf by 1818,” said study co-author Johannes Krause, a biochemist specializing in ancient DNA at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, in a Cell Press release.

Beethoven — famous for compositions like Bagatelle No. 25 (popularly “Für Elise”), Sonata No. 14 (“Moonlight Sonata”), and Symphony No. 9 — is one of the most beloved figures in music history. Tens of thousands attended his funeral on March 29, 1827.

He was a talented pianist and had an intimidating work ethic; when deafness beset him, Beethoven put a resonator on his piano to amplify its sound, and he eventually used vibrations to continue to compose.

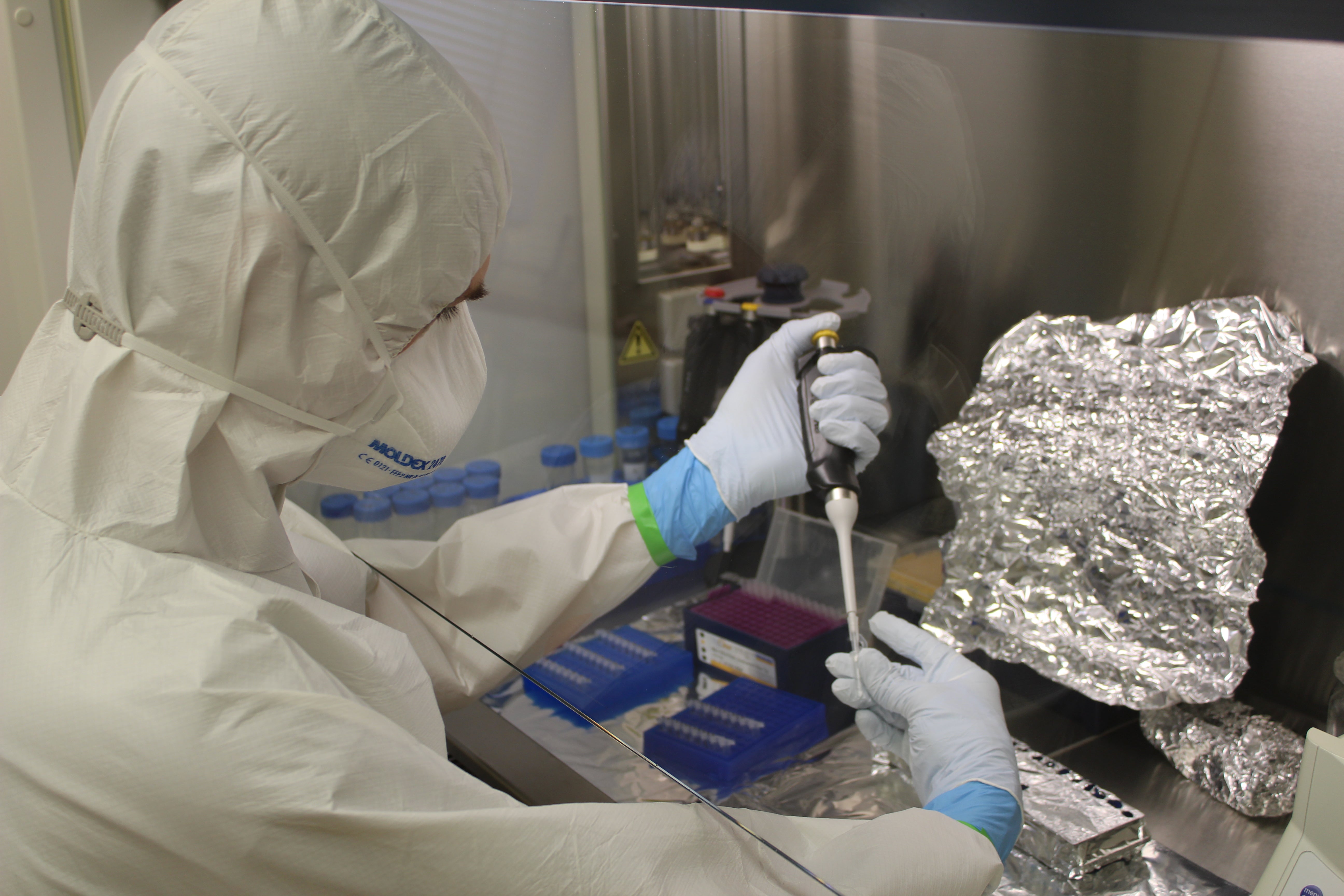

Though the researchers couldn’t determine a certain cause of Beethoven’s deafness, they gleaned numerous insights from his DNA. The genome was lifted from five preserved locks of wavy hair, passed down through different families and friends. Several other locks of hair previously attributed to the composer turned out to not be his, and one — called the Kessler lock — could not definitively be attributed either way.

Besides deafness, Beethoven suffered from gastrointestinal issues (gut pain and diarrhoea) and liver problems (including two bouts of jaundice) over the course of his life. The ailments became so severe that, in 1802, he asked his favourite doctor, Johann Adam Schmidt, to describe and publicise the nature of his disease after his death. (Schmidt ended up dying in 1809, 18 years before Beethoven). Beethoven’s death is now generally attributed to cirrhosis, or liver scarring.

Based on the genomic data, the team determined that celiac disease, lactose intolerance, and irritable bowel syndrome — all possible sources of gastrointestinal discomfort and, erm, violent excretions — were unlikely to have affected Beethoven.

Furthermore, Beethoven does not appear to have suffered lead poisoning; previous analysis that suggested as much was based on a hair sample that did not belong to him.

The composer’s death was almost certainly hastened by alcohol abuse. As noted by the researchers, some of Beethoven’s contemporaries claimed that the composer drank in moderation, but one friend allegedly claimed that, in the last few years of his life, Beethoven was drinking a litre of wine with lunch daily.

“There are metabolic biomarkers of chronic alcohol abuse that survive in hair, particularly one called EtG,” wrote study lead author Tristan James Alexander Begg in an email to Gizmodo. “Whether these biomarkers can be accurately analysed, with respect to chronic alcohol consumption, in hair, is a very big unknown, and would likely entail a large-scale study in order to validate such approaches,” explained Begg, an archaeogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

The team also compared Beethoven’s Y chromosome with five Y chromosomes from living descendants of Aert van Beethoven, an ancestor of Ludwig who lived from 1535 to 1609. (The team was able to reconstruct the Beethoven genetic patrilineage to about 1000 CE.)

But the Y chromosomes of the living men did not match those from the Beethoven hair samples; to the researchers, that indicated an extra-pair paternity — that is, an extramarital conception — somewhere between Aert van Beethoven and the birth of Ludwig seven generations later. That interloper provided the Y chromosome that eventually made its way into Ludwig’s genetic code.

Whether this means Beethoven himself was born from the extra-pair paternity is undeterminable, the researchers say.

Similarly, while the team was able to identity hepatitis B viral DNA in Beethoven’s hair, they were not able to determine when or how the infection occurred. Hepatitis B causes inflammation of the liver and can be transmitted from mother to child, through sexual interaction, or during surgery with contaminated tools.

“We cannot say definitely what killed Beethoven, but we can now at least confirm the presence of significant heritable risk, and an infection with hepatitis B virus,” Krause said. “We can also eliminate several other less plausible genetic causes.”

“Hepatitis B is likely the most promising vein of future research,” Begg said. “I would strongly advocate that additional locks of hair, dating from different periods in Beethoven’s life, undergo such analyses.”

While the results affirm some previously suspected conclusions, they also raise new questions about the origins of Beethoven’s many illnesses. And of course, perhaps the biggest mystery — the cause of his hearing loss — remains just that.

The Hiller lock

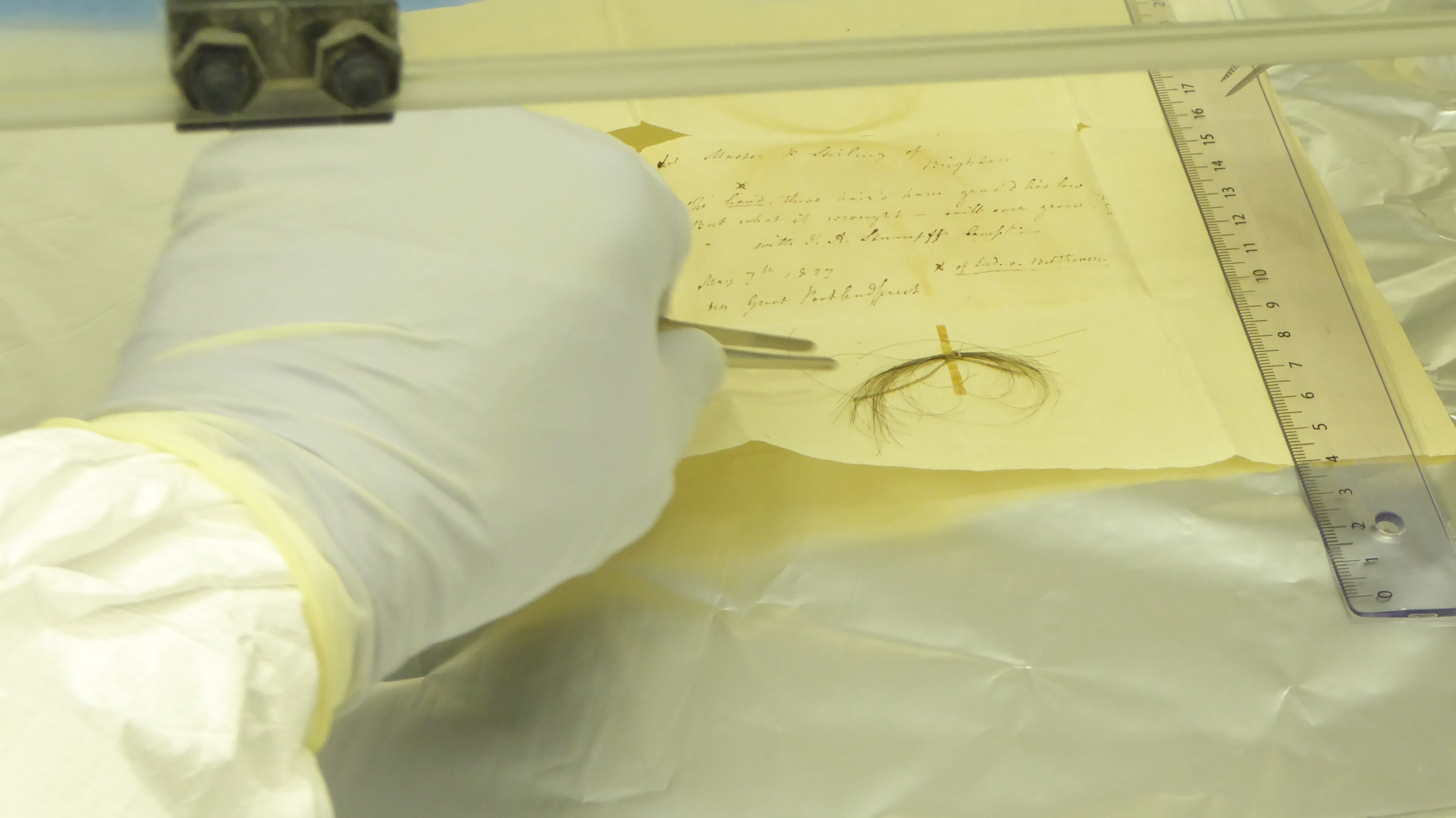

The researchers studied eight locks of hair associated with Ludwig van Beethoven. The Hiller lock (pictured above) turned out not to be a genuine lock of Beethoven’s hair; in fact, genetic analysis indicated it came from a woman.

The Halm-Thayer and Bermann locks

Both the Halm-Thayer lock and the Bermann lock were certified as authentic bits of Ludwig van Beethoven by the team’s analysis.

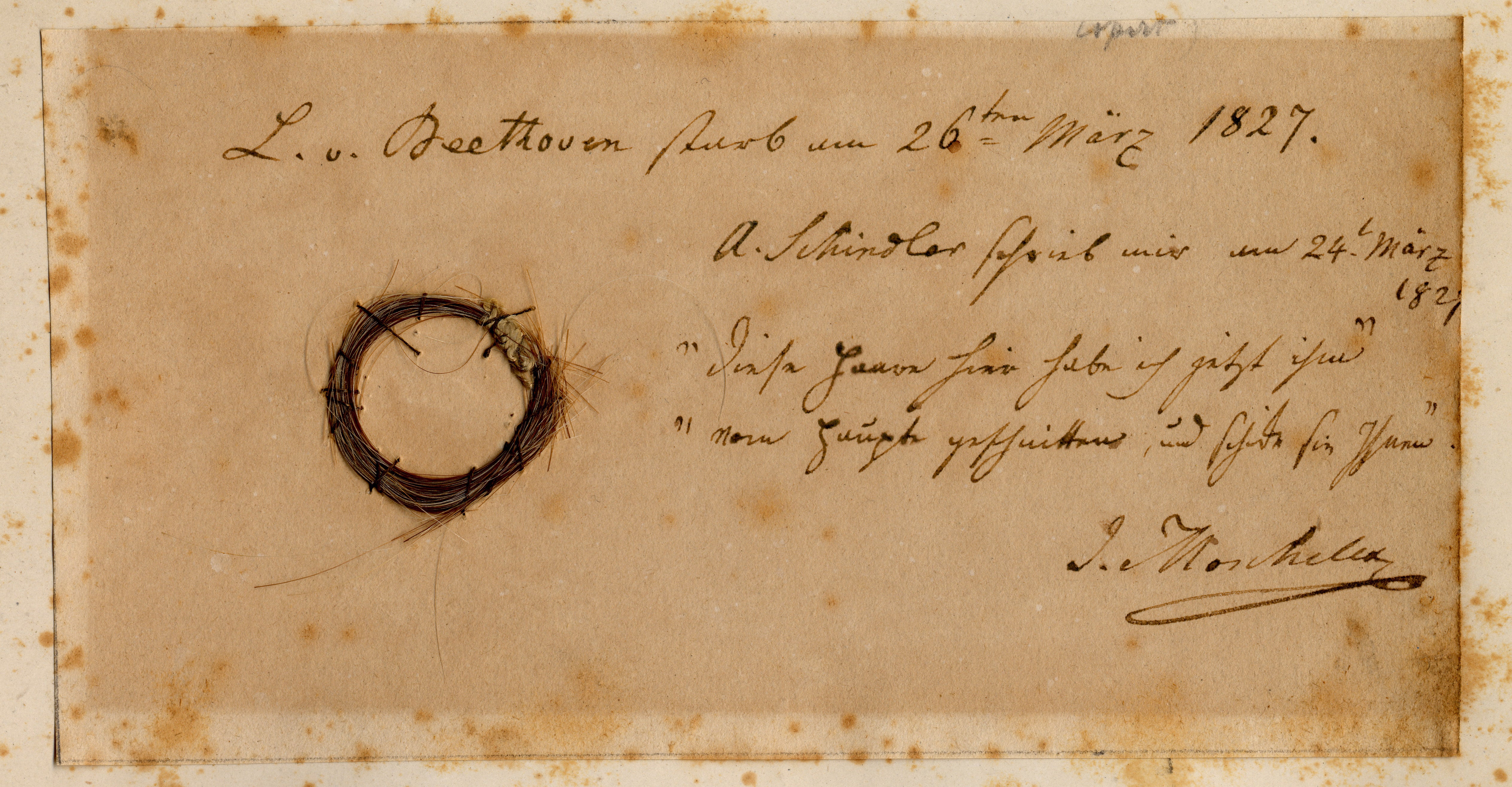

The Moscheles lock

The Moscheles lock, with an inscription from its former owner. Labwork on the lock confirmed its authenticity.

The Stumpff lock

The Stumpff sample belonged to Beethoven. It is the lock of hair from which the composer’s whole genome was sequenced, allowing the researchers to make new insights regarding Beethoven’s health and genealogical history.

Beethoven on his deathbed

Beethoven died on March 26, 1827. Years before his death, he asked his doctor to make public the cause of the ailments that troubled him for many years. Now, thanks to DNA preserved in locks of the composer’s hair and passed down through the centuries, geneticists are finding new details about the man’s health and what contributed to his death.