The coming age of powerful AI chatbots may very well reshape the world in radical and unforeseen ways, but it could do so at an immense environmental cost. A new report released today by the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence estimates the amount of energy needed to train AI models like OpenAI’s GPT-3, which powers the world-famous ChatGPT, could power an average American’s home for hundreds of years. Of the three AI models reviewed in the research, OpenAI’s system was by far the most energy-hungry.

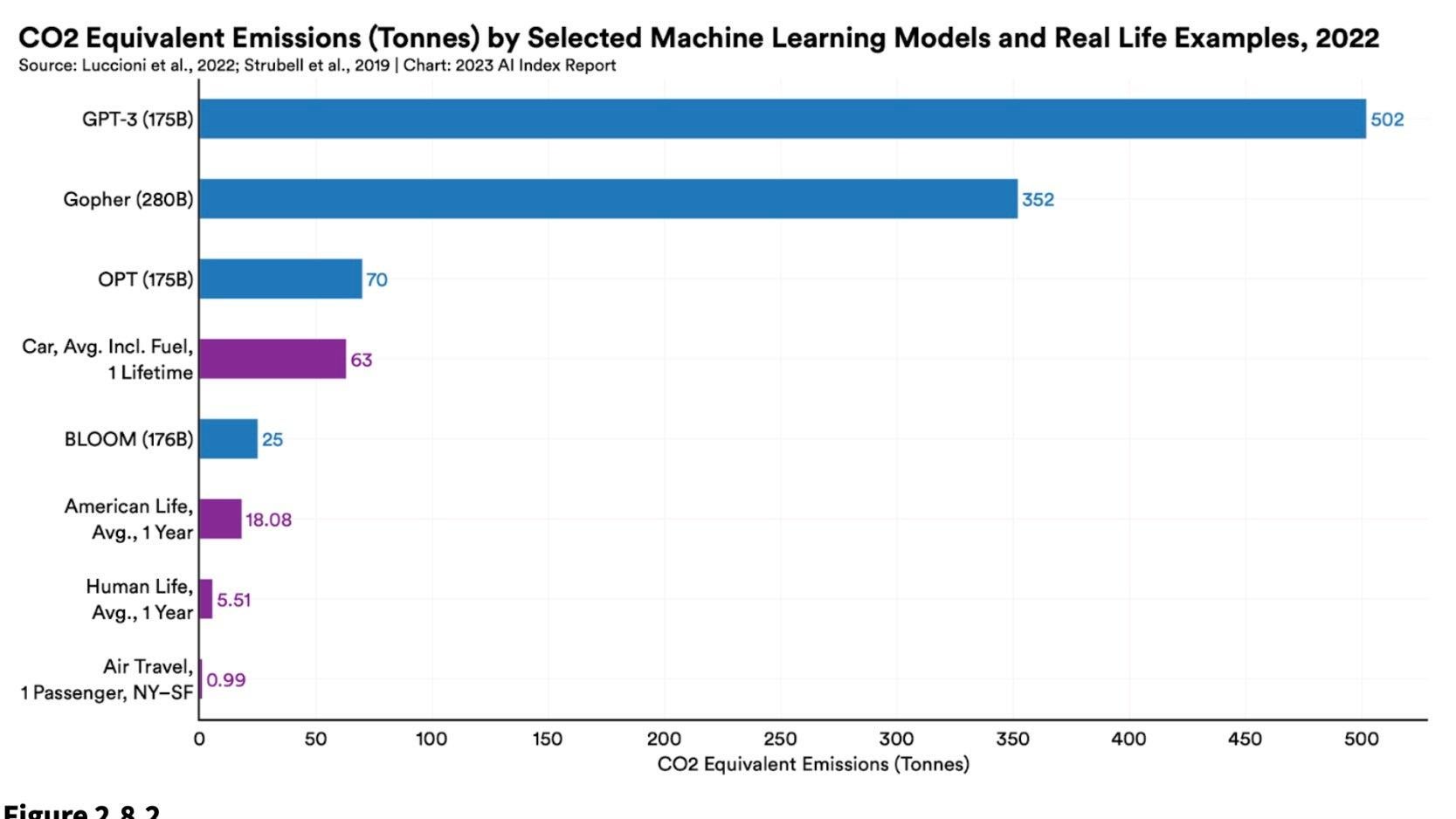

The research, highlighted in the Stanford recently released Artificial Intelligence Index, draws on recent research measuring the carbon costs associated with training four models: DeepMind’s Gopher, BigScience inititiaives’ BLOOM, Meta’s OPT, and OpenAI’s GPT-3. OpenAI’s model reportedly released 502 metric tons of carbon during its training. To put that in perspective, that’s 1.4 times more carbon than Gopher and a whopping 20.1 times more than BLOOM. GPT-3 also required the most power consumption of the lot at 1,287 MWh.

Numerous factors went into determining each model’s energy consumption including the amount of data points, or parameters, they were trained on and the energy efficiency of the data centres where they are housed. Despite the stark differences in energy consumption, three of the four models (excluding DeepMind’s Gopher) were trained on roughly equivalent 175 billion parameters. OpenAI won’t say how many parameters its newly released GTP-4 is trained on, but given the huge leaps in data required between previous versions of the model, it’s safe to assume GTP-4 requires even more data than its predecessors. One AI enthusiast estimated GPT-4 could be trained on 100 trillion parameters, though OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has since called that figure, “complete bullshit.”

This is a frightening visual for me.

The first dot is the amount of data Chat GPT 3 was trained on.

The second is what chat GPT 4 is trained on.

They are already doing demos.

It can write a 60,000 word book from a single prompt.

The only question I’ve had about AI… pic.twitter.com/DnAEMm60lh

— Alex Hormozi (@AlexHormozi) January 10, 2023

“If we’re just scaling without any regard to the environmental impacts, we can get ourselves into a situation where we are doing more harm than good with machine learning models,” Stanford researcher Peter Henderson said last year. “We really want to mitigate that as much as possible and bring net social good.”

AI models are undoubtedly data-hungry, but the Stanford report notes it may be too early to say whether or not that necessarily means they portend an environmental disaster. Powerful AI models in the future could be used to optimise energy consumption in datacenters and other environments. In one three-month experiment, for example, DeepMind’s BCOOLER agent was able to achieve around 12.7% energy saving in a Google data centre while still keeping the building cool enough for people to comfortably work.

AI’s environmental costs mirror the crypto climate dilemma

If all of this sounds familiar, it’s because we basically saw this same environmental dynamic play out several years ago with tech’s last big obsession: Crypto and web3. In that case, Bitcoin emerged as the industry’s obvious environmental sore spot due to the vast amounts of energy needed to mine coins in its proof of work model. Some estimates suggest Bitocin alone requires more energy every year than Norway’s annual electricity consumption.

Years of criticism from environmental activists however led the crypto industry to make some changes. Ethereum, the second largest currency on the blockchain, officially switched last year to a proof of stake model which supporters claim could reduce its power usage by over 99%. Other smaller coins similarly were designed with energy efficiency in mind. In the grand scheme of things, large language models are still in their infancy and it’s far from certain how its environmental report card will play out.

Large language models are getting absurdly expensive

Energy requirements aren’t the only figures shooting up with new LLMs. So are their price tags. When OpenAI released GPT 2 back in 2019, the Stanford report notes it cost the company just $US50,000 ($69,410) to train its model built on 1.5 billion parameters. Just three years later Google revealed its own powerful PaLM model trained on 540 billion parameters. That model costs $US8 ($11) million to train. PaLM, according to the report, was around 360 times larger than GPT-2 and but cost 160 times more. Again, these models, either released by OpenAI or Google, are only getting larger.

“Across the board, large language and multimodal models are becoming larger and pricier,” the report notes.

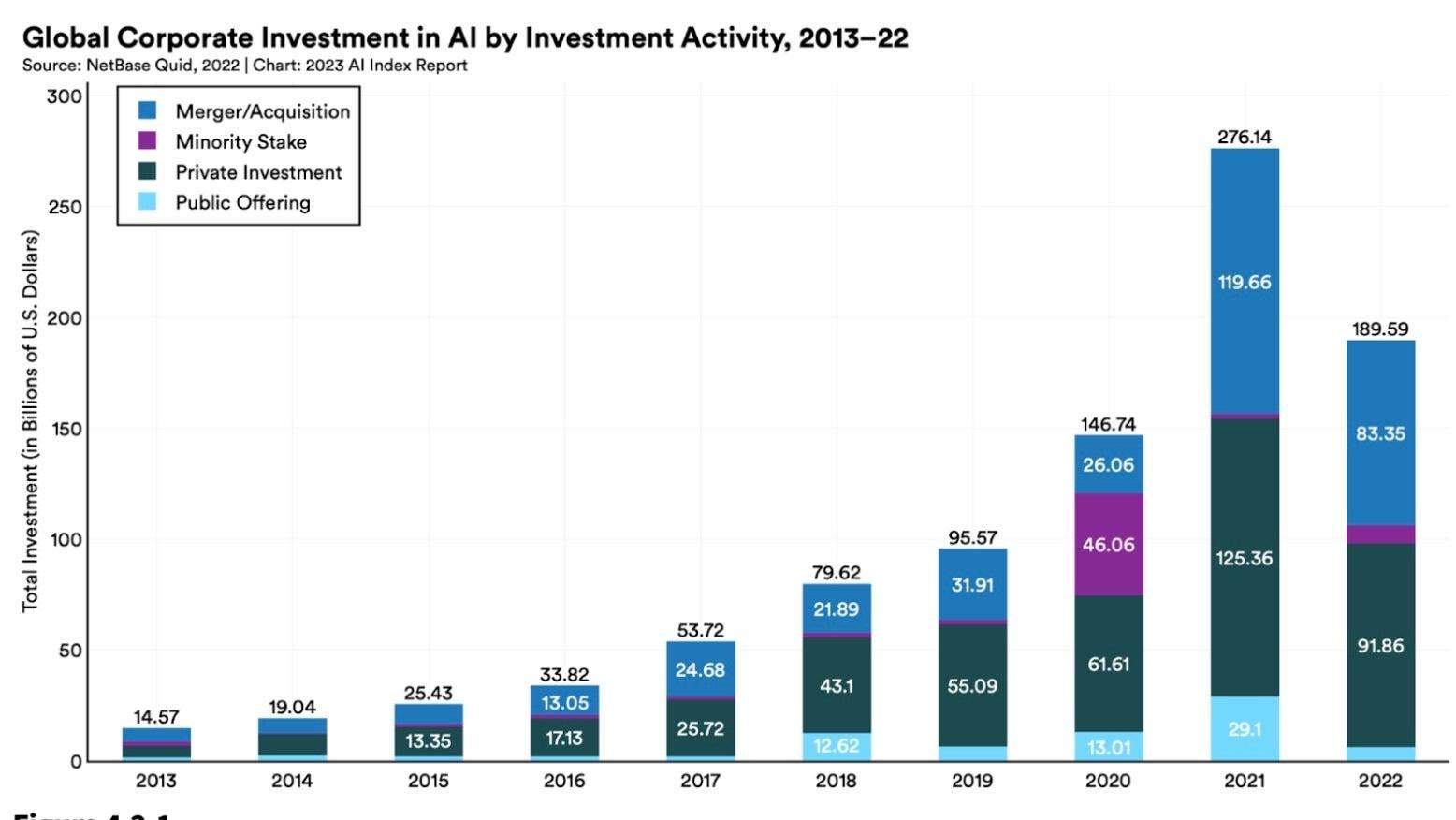

All that money could have carry-over effects in the wider economy. Stanford estimates the amount of private investment in AI globally in 2022 was 18 times larger than it was in 2013. AI-related job postings across every sector, in the US at last, are also growing, and increased from 1.7% to 1.9% in 2022. On the global scale, the US remains unmatched in terms of overall investment in AI and reportedly invested $US47.4 ($66) billion into AI tech in 2022. That.s 3.5 times more than China, the next largest spender. When it comes to burning money, America is unmatched.

Lawmakers try to play catchup

The recent wave of powerful chatbots and ethical and legal questions surrounding them snuck up on just about everyone outside of AI engineers, including lawmakers. Slowly but surely, lawmakers are trying to play legislative catch-up. In 2021, according to the Stanford report, just 2% of all federal bills involving AI actually passed into law. That figure climbed up to 10% last year. Many of those bills similarly were written prior to the current hysteria around GPT4 and some researcher’s premature descriptions of it as “artificial general intelligence.”

Lawmakers are also more interested in AI than ever before. In 2022, Stanford identified 110 AI-related legal cases brought in US federal and state courts. That might not sound like much, but it’s still 6.5 times more cases than were spotted in 2016. The majority of those cases took place in California, Illinois, and New York. Around 29% of those AI cases involved civil law, while 19% concerned intellectual property rights. If recent complaints lodged by writers and artists over AI generators’ use of their style are any guide, it’s possible that the portion of property rights cases could increase.

Want to know more about AI, chatbots, and the future of machine learning? Check out our full coverage of artificial intelligence, or browse our guides to The Best Free AI Art Generators and Everything We Know About OpenAI’s ChatGPT.