Researchers have identified a gene that is associated with taller noses in humans and found it likely comes from Neanderthals, an extinct hominin group intimately related to our own species.

Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) died off around 40,000 years ago, making them the most recent hominin species to go extinct. But, in a way, they are still around, since most humans today are walking around with Neanderthal DNA. Lots of interbreeding between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals may have resulted in their species being subsumed by ours.

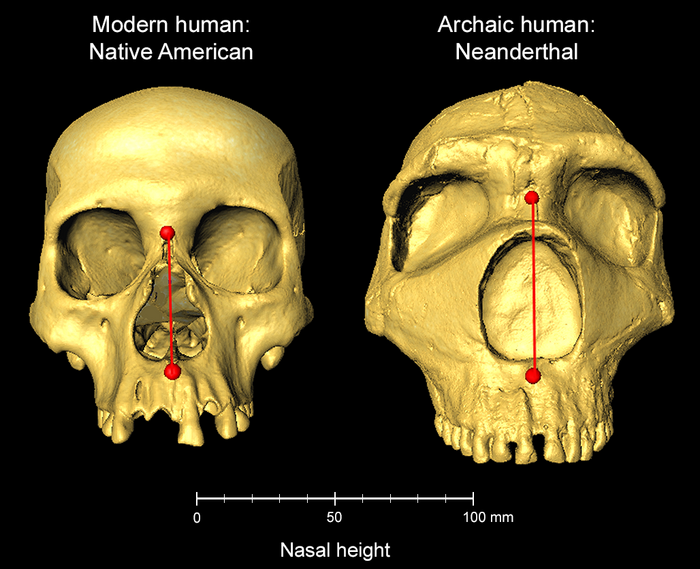

Long stereotyped as brutish oafs, Neanderthals were actually highly sociable and intelligent. Physically speaking, they were shorter than modern humans, with barrel chests and pronounced brows. They also had broad, tall nasal passages, which the researchers believe has resulted in the nose shape of many people today.

In their new research, published today in Communications Biology, the interdisciplinary team studied genetic information from 6,000 modern humans of mixed European, Native American, and African ancestry from Latin America. They then cross-referenced the genetic findings with measurements of the individuals’ facial features, especially of their noses.

“Most genetic studies of human diversity have investigated the genes of Europeans; our study’s diverse sample of Latin American participants broadens the reach of genetic study findings, helping us to better understand the genetics of all humans,” said study co-author Andres Ruiz-Linares, a geneticist at Fudan University, University College London, and Aix-Marseille University, in a UCL release.

The gene the team deemed responsible for tall noses in some humans is the Activating Transcription Factor 3 (ATF3). The gene is not known to be involved directly with the development of the human face. However, the researchers note that, back in 2007, a different team found expression of ATF3 is regulated by another transcription factor, FOXL2, mutations of which “are known to lead to alterations of the midface.”

Beyond that association, they found that little bits of genetic code known as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that appear around ATF3 were found around elements of DNA that are active during the development of the head and face.

The Neanderthal genome was sequenced over a decade ago, allowing scientists to better understand our ancient near-relations and, by proxy, what makes us human. (A lot of that work was spearheaded by Svante Pääbo, who last year was recognised with a Nobel Prize for his contributions to paleogenetics.)

While ATF3 is not itself a smoking gun for Neanderthal honkers nosing their way into our genome, the odds and ends within the gene suggest a link.

“It has long been speculated that the shape of our noses is determined by natural selection; as our noses can help us to regulate the temperature and humidity of the air we breathe in, different shaped noses may be better suited to different climates that our ancestors lived in,” said Qing Li, a geneticist at Fudan University and lead author of the study, in the same release.

“The gene we have identified here may have been inherited from Neanderthals to help humans adapt to colder climates as our ancestors moved out of Africa,” Li Added.

Among Neanderthals’ physiological characteristics was a broad, tall nose with wide nostrils. As reported in 2018 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, one theory is that the Neanderthal nose size was helpful for breathing deeply in cold, dry climates.

Whether to take in extra air or to warm and humidify the air before it reached their lungs, the Neanderthal body was built for endurance. Neanderthals in Italy dove for shellfish; maybe their large noses helped the groups in Mediterranean climes take a deep breath before going underwater.

40,000 years later, remnants of our lost relatives live on in our modern gene pool.