The Webb Space Telescope’s latest subject is a wet one: a gigantic plume of water vapour spewing from Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

Webb launched in December 2021 and has since been using its infrared gaze to investigate some of the oldest light in the universe, as well as objects local to our solar system. Examining other planets, like Uranus, and their moons is a useful way of understanding the dynamics between heavenly bodies and how they may have formed.

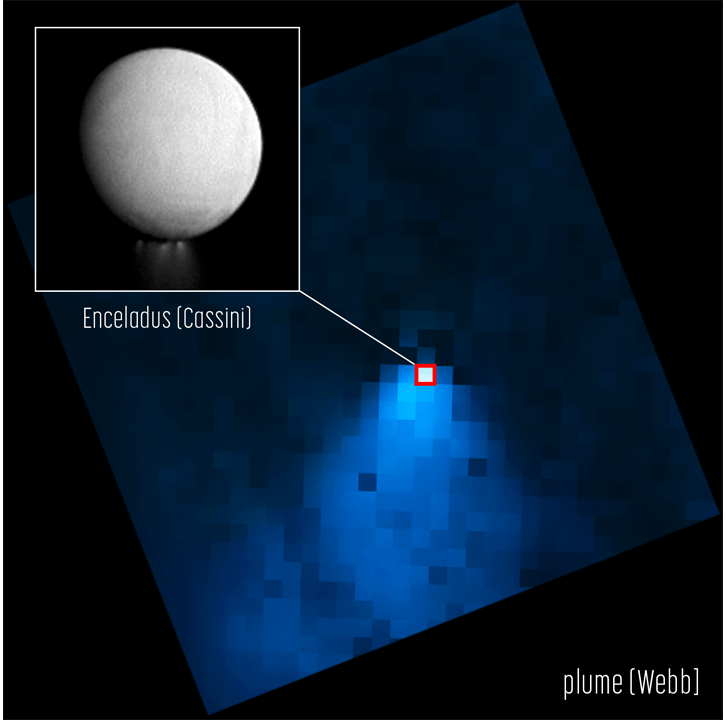

Enceladus is a tiny, icy moon orbiting Saturn. It’s a little over 483 kilometres across — less wide than the United Kingdom. In the 2010s, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft discovered geyser-like jets of water vapour, apparently from a subsurface ocean lurking beneath the moon’s surface.

Webb found that the recently spotted plume of water vapour spans over 9,660 km in length — a distance many times greater than the width of Enceladus itself. A team of astronomers described findings based on the image in a paper set to publish in Nature Astronomy; a preprint of the paper can be viewed here.

“When I was looking at the data, at first, I was thinking I had to be wrong. It was just so shocking to detect a water plume more than 20 times the size of the moon,” said lead author Geronimo Villanueva, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre, in a Space Telescope Science Institute release. “The water plume extends far beyond its release region at the southern pole.”

Villanueva added that the Webb image indicated that there was “water absolutely everywhere.”

The team found Enceladus’ geyser was spewing vapour at a rate of 299 l per second, feeding the halo of water vapour around the moon. As Enceladus ejects the vapour, it also feeds the water supply ringing Saturn. By the team’s measure, about 30 per cent of Enceladus’s water remains in the torus of water in the immediate vicinity, while the rest of the water feeds the rest of the system.

“Right now, Webb provides a unique way to directly measure how water evolves and changes over time across Enceladus’ immense plume, and as we see here, we will even make new discoveries and learn more about the composition of the underlying ocean,” added Stefanie Milam, also a planetary scientist at NASA Goddard and a co-author of the paper, in the same release.

“Because of Webb’s wavelength coverage and sensitivity, and what we’ve learned from previous missions, we have an entire new window of opportunity in front of us,” Milam added.

Water oceans on other planets and moons are intriguing sites for planetary scientists; since water is crucial for the persistence of life as we know it, researchers hope that by following water in the solar system, they may find life — or at least signs of where it could exist beyond our planet.