Astronomers found a new moon orbiting Uranus, as well as two around Neptune. The tiny satellites appeared as faint specks in the outer reaches of the solar system following hours of ground-based observations.

Using observatories in Chile and Hawaii, Scott Sheppard, an astronomer at the Carnegie Institution for Science, first spotted the Uranian moon on November 4, 2023 and the two previously unknown Neptunian moons in September 2021. “The three newly discovered moons are the faintest ever found around these two ice giant planets using ground-based telescopes,” Sheppard said in a statement. “It took special image processing to reveal such faint objects.”

Uranus’ new moon is the first to be discovered around the ice giant in more than 20 years and is likely the smallest of its 28 moons. The moon is only 5 miles wide (8 kilometers) and takes 680 days to complete one orbit around Uranus. Most of Uranus’ moons are named after characters from Shakespeare (e.g., Ophelia, Sycorax, Juliet, Desdemona, etc). Although it has been labeled as S/2023 U1 for now, the moon will eventually be renamed to keep up with the tradition.

The brighter of the two Neptunian moons, S/2002 N5, is 14 miles wide (23 km) and takes almost nine years to orbit around the farthest known planet from the Sun. Sheppard used the Magellan telescopes in Chile to confirm the orbit of S/2002 N5 in October 2021 and again in 2022 and November 2023, and traced it back to an object that was first spotted near Neptune in 2003 but lost before its orbit could be confirmed.

Neptune’s fainter new moon, S/2021 N1, measures at 8.6 miles wide (14 km) and takes 27 years to complete an orbit. As the faintest moon ever discovered using ground-based observations, S/2021 N1 required ultra-pristine conditions at the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope and Gemini Observatory’s 8-meter telescope in order to secure its orbit, according to Carnegie Science.

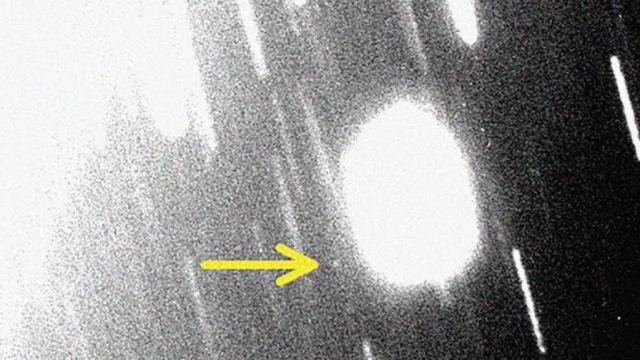

Sheppard, with the help of scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the University of Hawaii, Northern Arizona University, and Kindai University, captured five-minute exposures over periods of three or four hours on several nights in order to confirm the discoveries.

“Because the moons move in just a few minutes relative to the background stars and galaxies, single long exposures are not ideal for capturing deep images of moving objects,” Sheppard said. “By layering these multiple exposures together, stars and galaxies appear with trails behind them, and objects in motion similar to the host planet will be seen as point sources, bringing the moons out from behind the background noise in the images.”

All three of the new moons have eccentric, distant, and inclined orbits that suggest they were captured by the gravitational tug of Uranus and Neptune after the ice giants had already formed.