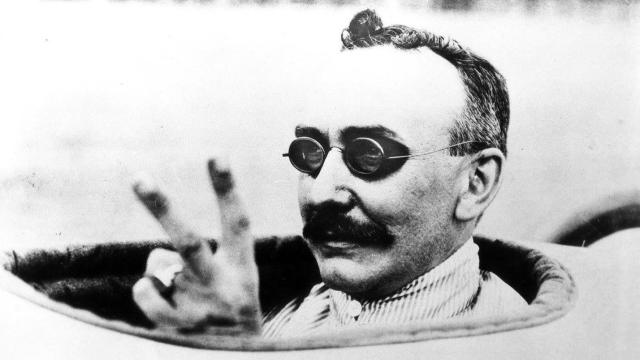

You’ll be forgiven for not knowing much about the automotive world around the mid-1890s. It was a long time ago, and the world was a very different place back then. The automobile was pioneered by thousands of people making iterative improvements to four-wheeled transport, some more important than others. History remembers the Henry Fords and John D. Rockefellers, but I would argue that Walter C. Baker was more interesting than either.

In his engineering work, he developed the shaft drive system, “floating” ball bearing rear axles, effectively invented car seat belts, and sold thousands of electric cars in the early 1900s. He was a restless and relentlessly brilliant engineer, and a speed demon at heart. Perhaps his most interesting feat, Baker designed the first car to exceed 100 miles per hour, and you bet your ass it was electric.

Baker Motor Vehicle Company

Baker and a friend started the American EV industry by bolting an industrial electric motor to a buckboard in 1896. Just three years later, with investment from his father-in-law, The Baker Motor Vehicle Company had started producing and selling Cleveland, Ohio-built EVs. By the early 1900s some 38 per cent of cars in the U.S. market (then only about 8,000 cars strong) were electric, and Baker was far and away the number one in sales.

Racing To Sell Cars

The old adage of “win on Sunday, sell on Monday” is a very old one, maybe even older than the car itself. And it’s one that Walter Baker took to heart. After his factory was set up and operational, Baker set out to prove that his electric cars were better constructed, more efficient, and faster than any other automaker on the planet.

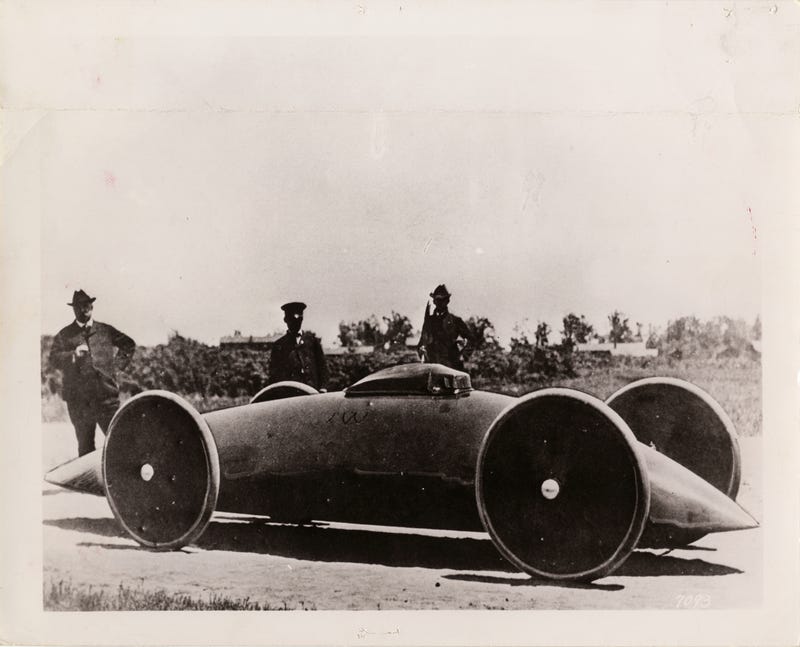

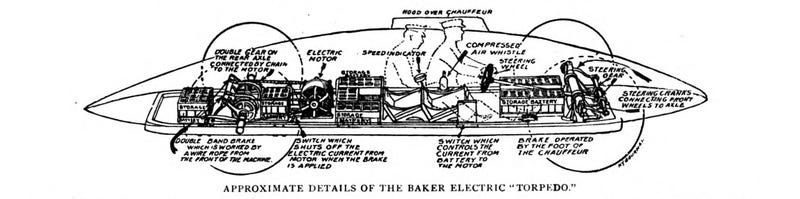

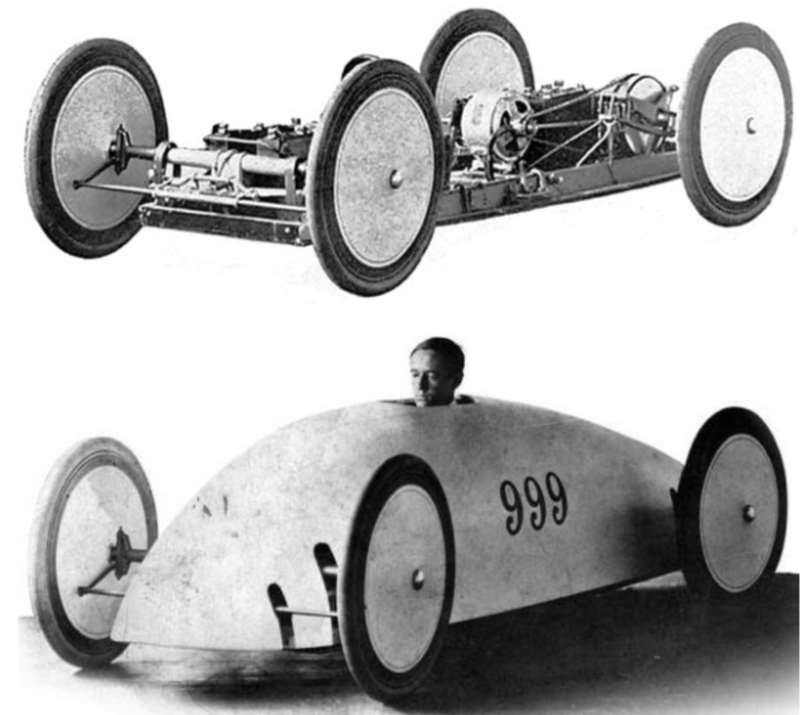

Mr. Baker was inspired by a Belgian named Camille Jenatzy, who cranked the speed record up to 66 miles per hour by 1900. The American EV evangelist used $US10,000 of his own money (about $US357,000 today) building his first of three speed questing vehicles. Over the course of two years, the first Baker Torpedo was built. When it wheeled out of the workshop, it was a 3,100 pound electric-powered hand-rolled cigar—constructed of white pine with an aluminum body shell—ready to prove its mettle in the crucible of competition.

With a rack of 11 lead-acid batteries powering a 14-horsepower Elwell-Parker electric motor turning a double chain to the rear axle, it was among the most powerful machines in the world. It may not seem like it now, but 120 years ago 14 horsepower was a lot. In order to “cheat the wind” the car was shaped like “a falling drop of oil” and the 36-inch wire-spoked wheels were given inner and outer disc covers. In order to keep the car’s frontal area to a minimum, the driver and brakeman seats were mounted in tandem.

A report appearing in newspapers across the country reported the Torpedo’s maiden outing as follows:

A NOVEL HIGH-SPEED ELECTRIC MOTOR

This electric car was built by the Baker Electric Vehicle Company of Cleveland to beat all records, but it came to serious grief a short time on since on the Staten Island racing track. After a forty seconds’ burst at teriffic speed, it got beyond control and dashed into the crowd, killing and injuring nearly twenty persons, and then absolutely went to pieces. Mr. W.C. Baker (the owner and designer) and his chauffeur escaped almost miraculously without so much as a scratch. On account of its peculiar construction the car had attracted much attention, and its trial was awaited with marked interest. It was shaped something like a cigar cut in half lengthwise, and when in motion it has been compared with a miniature submarine torpedo-boat mounted on wheels. It was built for speed, and to attain speed almost everything else was sacrificed. A broken wheel was the primary cause of the trouble.

It’s true, the Memorial Day 1902 running of the Torpedo on Staten Island ended in tragedy. In an attempt to set a standing mile record on a paved street in New York, the car swerved erratically coming out of a slight bend in the course, and struck trolley tracks at an angle which snapped one of the wheels, spinning the car broadside into the crowd. Two died, but Baker and his brakeman—C.E. Denzer, Baker’s chief mechanic—were safe, in part because the shoulder harnesses that Baker had installed in the car kept them upright and seated in their hammock-style lightweight seats. While the car didn’t make it to the standing mile, it completed a measured flying kilometer in 36 seconds, averaging nearly 70 miles per hour. W.C. Baker and C.E. Denzer were the fastest men in the world.

It was this deadly incident that ended all top speed events on public streets in the U.S. Baker briefly gave up on the idea of setting a speed record, and retired the Torpedo. Many who still sought speed, but wanted to do so without harming the general public, sought a solution and developed the 1903 races on the Daytona-Ormond beaches in Florida.

The Kid Tries Again

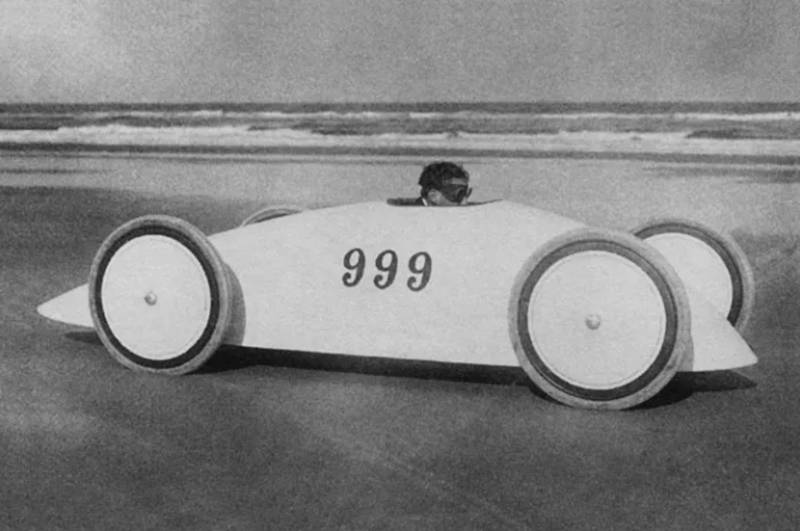

After sitting out the inaugural Daytona-Ormond event, Baker built a pair of smaller and lighter “Torpedo Kid” machines for 1904. Baker wasn’t satisfied with the weight of the original Torpedo, and set out to develop a single-occupant racer of reduced size. Instead of a metal body, the Kid used a wood and canvas body, and the wheels were covered over in oil cloth. It looked like something straight out of the future compared to the competition, and it performed like it, too.

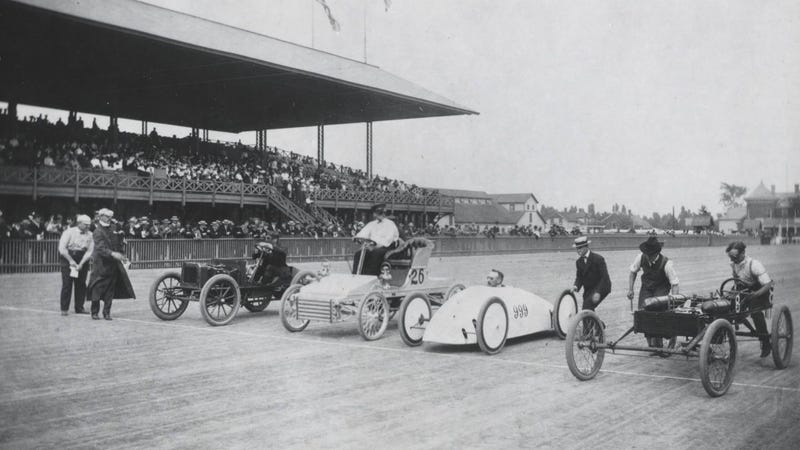

By this point Baker’s speed record had been bested, and he needed to go even faster than he had in 1902. The much smaller car, dubbed “The White Mouse” by onlookers, was eerily quiet by comparison to its contemporary competitors, but also geared for much higher speeds. It didn’t out-accelerate the gasoline or steam cars in 1904, but Baker was aiming for a much more impressive number he could use to spread the word about his electric daily drivers.

Baker had stopped racing as a driver in 1903 after another crash in 1903 injured four spectators at an oval track in his Cleveland hometown. For the 1904 event in Florida he hired driver W.J. Hastings to drive the Torpedo Kid. While the only Baker record to officially hit the books was Hastings’ standing mile run in 1 minute and three-fifths of a second, the car was capable of much more. Officially the car was recorded as running 104 miles per hour, making the Baker Torpedo Kid the fastest car on the planet.

Wanting to prove that the car was capable of more, Baker allegedly stepped aboard and unofficially sent the car to 136 miles per hour. It’s possible that the car could have gone even faster, but reports from the day say the Torpedo Kid’s wheels fell off at speed, and Baker packed it up and went back to Ohio, never to race again. Now that’s going out on top, baby!

The Wright Flyer first took to the air at Kitty Hawk on December 17, 1903. On February 1, just 46 days later, fellow Ohioan Walter Baker drove his aerodynamic electric racing car to 136 miles per hour. Both are astonishing feats taking money, genius, and steel resolve to accomplish, but one is remembered as a part of history, and the other has been lost to the annals of time.

No car would get even close to Baker’s unofficial speed on the beaches of Daytona until Barney Oldfield (strangely also from Ohio) took his famous 21.5-liter Blitzen Benz racer to 131.723 mph seven years later. It took until 1968 for an electric vehicle to go faster than Baker, when Jerry Kugel took Autolite’s Lead Wedge to 139.89 mph at the Bonneville Salt Flats.