A few years ago, I bought a bright orange city bike, which I chose because it allowed me to sit up as I rode. A few times a week, I wear my regular clothes — mostly dresses — to go to meetings, run errands or ride on the bike path by my house. I don’t own any padded shorts. What would you call me?

A New York Times op-ed that made the rounds last week called people like me a “cyclist”. So did an entire series on biking in the Los Angeles Times. In fact, most stories about bikes or biking lump every kind of bike rider, from cruising tourists to city commuters to training racers, into this single category.

But every time someone refers to me has a cyclist, I shake my head. A cyclist is someone wearing those padded shorts, hunched over a bike with clip-in pedals — someone who’s more likely to be heading to a triathlon on the weekend instead of putting crepe paper through her spokes and toodling downtown to meet some friends for brunch.

It turns out, I’m not alone in this. “To me, and many others, ‘cyclist’ brings to mind someone wearing Lycra, riding a performance bike — someone who is engaged more in a sport than a mode of transportation or accessible recreation,” says Carolyn Szczepanski, director of communications at the League of American Bicyclists. “While we absolutely embrace those riders, it doesn’t paint a full, realistic picture of the people who are riding — both for advocacy and outreach purposes and public perception purposes.”

Would you call these people cyclists? Top: A “hipster on a fixed gear bike,” photo by solominviktor; Bottom: “visionary cargo bike mum” Shelby Sanchez rides with her kids in Long Beach, California, photo by Lisa Beth Anderson for Pedal Love

Even biking publications are pulling away from the term. “We try to avoid the word ‘cyclist’ consciously as much as possible,” says Mia Kohout, CEO and editor-in-chief of Momentum Magazine. “The word evokes a lot of negative connotations. There’s a huge group of people — 60 per cent of the people in cities — who are interested and concerned about riding a bike, but the word seems too hardcore to them.”

From an advocacy standpoint, getting rid of the word “cyclist” removes perceptual barriers that prevent people from trying biking in the first place, says Dave Snyder, executive director of the California Bicycle Coalition. “It makes biking accessible to anyone, and diminishes the sense of biking as an activity for a subculture or one that requires an ‘identity’ to engage in. Someone who has a bike in their house somewhere and only occasionally rides it and never would consider themselves a ‘cyclist’ is someone we should definitely reach out to.”

In short, “cyclist” might be too narrow of a word to describe many Americans on bikes today. But it’s more than just semantics. The word “cyclist” may be making biking more unsafe.

“I personally think the word ‘cyclist’ is too mechanised and allows others to not consider ‘cyclists’ people,” says Alexis Lantz, a policy analyst with the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health and former policy director for the Los Angeles County Bicycle Coalition. The term, she says, focuses more on the bike itself — on an object, not a person — as opposed to who’s riding it, obscuring the fact that there’s a living, breathing human behind the handlebars.

Instead, Lantz and many other advocates recommend ditching “cyclists” for a simple yet important replacement: “people on bikes.”

“People who ride bikes” or “people on bicycles” puts the emphasis back on the human activity, says Szczepanski. “We want to put ‘people’ first. We want to make sure that policymakers, motorists, everyone recognises that we are your mothers, sisters, friends, neighbours who are using this great tool — a bicycle — and deserve to be safe and respected like everyone else.”

A safety campaign by Bike Pittsburgh focuses on people and avoids the word “cyclist”

Of course, not all bike advocates agree that this is a battle worth fighting. At this month’s California by Bike Summit in Oakland, this debate arose during a workshop on reaching out to groups underserved by biking. “Some people feel strongly about keeping the word ‘cyclist’ intact as the standard for simplicity’s sake,” says attendee Maria Sipin, a health communications specialist at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. “Others demand more diversity and inclusion, which can be achieved by using language that appeals to more people.” Sipin believes it’s a personal choice: “As a road safety instructor, I give people the option to self-identify and describe their own experience on bikes.” What does Sipin call herself? “A person who loves to ride a bicycle,” she says.

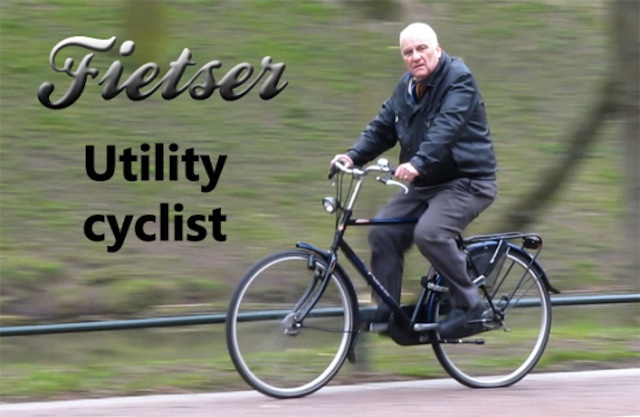

A phrase like that, while accurate, can be a real mouthful — or a nightmare for a newspaper editor’s word count. So maybe we need to coin a new word entirely. For precedent here, we can look to The Netherlands where, in some cities, up to 70 per cent of all trips are taken by bike. According to Mark Wagenbuur, who blogs at the site Bicycle Dutch, there’s a very interesting differentiation between the English and Dutch languages when it comes to biking.

The Dutch word for bike is fiets, but that word can only describe what we Americans would call a city bike or sit-up bike. If the bike in question is what we’d call a racing bike or a road bike, they’d call that race fiets or wielrenfiets. “The same goes for fietser or cyclist,” writes Wagenbuur. “To a Dutch person that can never be someone in specific clothes on a race fiets. The Dutch have a different word for those people, they call them wielrenner — literally ‘wheel runner,’ and it is pronounced almost like that. A fietser is someone in everyday clothes on a sit-up bike — and nothing else!”

Helpful illustrations for the Dutch words for “people on bikes” and “cyclists,” images via Bicycle Dutch

Of course, it may not even be that simple. Professional triathlete Jennifer Tetrick is proud to call herself a cyclist, even though she acknowledges the stereotypes around the term. But the other categories are not so cut-and-dried, she says. She sees different types of bikes creating their own kinds of cliques — fixed-gear bikes, beach cruisers, lowriders, folding bikes, commuter bikes, recumbent trikes — and also notes that people can move between the labels, like a person who starts out riding to work and eventually decides to race. “I wouldn’t want to get stuck in the language,” says Tetrick. “We get so caught up in what defines us in some ways instead of what unites us as people who love bikes and want to see more people on bikes. People have to start riding somewhere.”

The issue is only going to become more complex as more Americans take to the streets in whatever kind of new two-wheeled contraptions are are on the horizon, resulting in perhaps even more new terminology. Maybe it’s time bike riders stop sub-labelling themselves at all, says Kohout. “I might use a bike to get around, but do we want to identify ourselves by the tools we use to get from point A to point B?”

“At one level it’s kinda silly,” agrees Snyder. “Do I consider myself a ‘motorist’ because I sometimes use a car?”

But that’s exactly why the “people who bike” model works so well. We could extrapolate it across the entire world of transportation to bring back empathy and renewed attention to the people — the actual people — on our streets. Try saying “people who drive” instead of “drivers,” or “people who walk” instead of “pedestrians.” Suddenly this passive, faceless term that usually connotes a victim or someone at fault turns into a more active, visual description of an actual human who is choosing to do something. I can identify more with a “person who drives” or a “person who walks” or a “person who uses a wheelchair” or a “person who rides the bus” or a “person on a Segway,” even if I don’t do any of those things, because I understand, even beyond their mode of transit, they’re still people.

If there’s any group that could help guide this change, it’s the League of American Bicyclists. The organisation was founded in 1880 as the first advocacy organisation for people who rode bikes, The League of American Wheelmen.