When an unexpected power surge sparked the world’s worst nuclear accident in Chernobyl, nearly a quarter of a million construction workers risked their lives to build an ad hoc “sarcophagus” of concrete around the stricken reactor. It was a stop-gap measure — and now, almost 30 years later, one of the biggest engineering projects in history is underway to protect it.

Image: AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky.

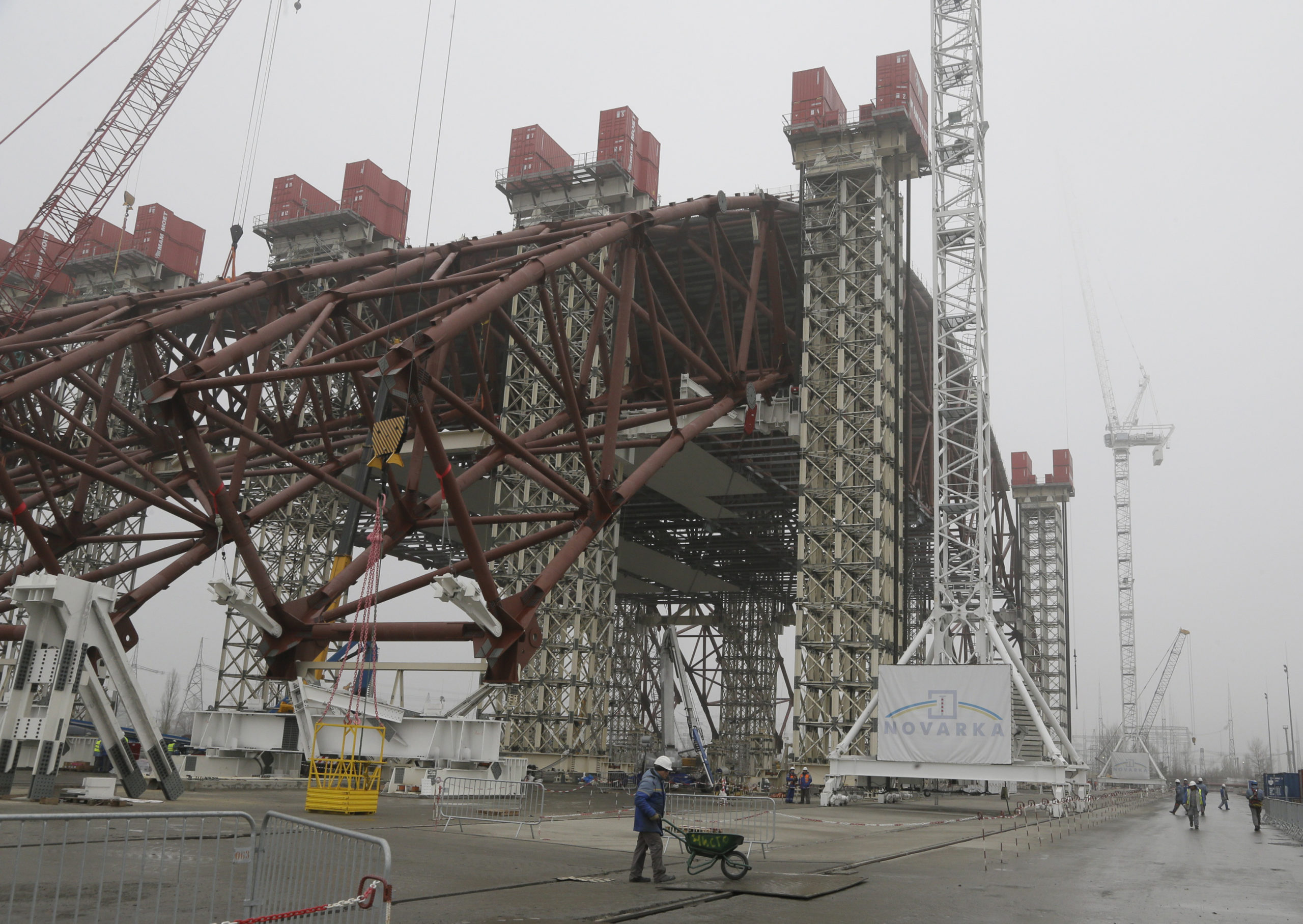

The BBC reports on the $US2 billion project to protect the decaying metal sarcophagus, using an even larger metal shield called the New Safe Confinement, or NSC. In simple terms, the NSC is a massive steel archway that is designed to protect the surrounding region if the 27-year-old sarcophagus eventually collapses. The design was proposed back in 1992 by a team of British engineers, but planning has taken more than a decade — the project is now halfway complete, with a target date of 2015 for final completion.

There are myriad reasons it’s taken so long to get the NSC up and running, the first being the sheer scale of this 100m tall protective shield. Since it will cover the existing sarcophagus, the arch is big enough to house the Statue of Liberty and wide enough to accommodate a soccer field. It’s being built by thousands of workers and engineers from all over the world, each of whom has a monthly and yearly exposure limit based on where, and for how long, they work on the site.

Image: AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky.

But it isn’t just the scale that’s extraordinary — it’s the unusual way in which it must be built, since the sarcophagus is still too radioactive for sustained human presence. The crux of the plan — the reason why it was chosen in 1992 — is the fact that would be built off-site and then slid over the current sarcophagus using railroad ties.

The 26,000-tonne structure is taking shape several hundred metres away from Reactor 4, helping to limit the radiation exposure of workers.

Image: AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky.

It’s not quite as simple as putting a cap on a pen, though. The biggest complication is a tall metal chimney above Reactor 4, which must be removed before the archway can slide into place. Workers can only spend a few hours at the reactor site before they reach the maximum radioactive exposure limit, and work is thus progressing at a snail’s pace:

Work has started removing sections weighing up to 55 tons each. They must be cut off with a plasma cutter by teams of two men and removed by crane — a nerve-wracking process. If a crane fails, or an operator miscalculates, and a section falls into the reactor, this too could release a new cloud of radioactive dust into the atmosphere.

Despite the incredible lengths required to build the structure, it’s still only a band-aid: Designed to last for roughly 100 years, it is a more sophisticated solution to a problem scientists still don’t know how to solve. The hope is that, within the next century, we’ll have the technology to extract the reactor and the spilled fuel and deposit them — maybe in glass — somewhere safe. [Studio-X NYC; BBC]

Images: AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky.