You’d think that, as a company accused of fostering oppression for years, SodaStream would be a little more careful about the wording of its biggest-ever marketing campaign.

But its new Super Bowl-ready, Scarlett Johansson-backed tagline, “Set the bubbles free”, has been all too easy for the company’s many ardent opponents to twist to their advantage:

Set the bubbles free! Palestinians can wait.

Through a combination of clever marketing (hello ScarJo) and the fact that its product actually works on a consistent basis, the SodaStream brand has effectively become the catchall term for soda-making machines as a whole. It’s the Kleenex of carbonated liquids. More importantly, it’s positioned itself on a platform of guilt-free sustainability, saving hundreds of thousands of plastic bottles so you can down fizzy glass after fizzy glass with a clearer conscience and a greener Earth left in your wake.

It’s this same meticulously crafted image of a moral high ground, though, that has so many of SodaStream’s liberally minded devotees surprised to learn that their environmentally conscious company actually has human rights activists enraged.

On Sacred Ground

You may have seen SodaStream in the news lately because of the ScarJo spotlight, but it’s hardly a new issue. Since late 2011, various groups have attempted to call attention to the Israeli company’s factory in the West Bank settlement of the Mishor Edomim Industrial Zone. And the factory itself has been open since 1996, back when the company was known as Soda Club.

It may be just one of SodaStream’s 20 factories scattered around the world, but the Mishor Edomim facility also just so happens to sit atop highly controversial, Israeli-occupied territory in the West Bank. A location that, according to protestors, is both hindering the peace process and allowing SodaStream to profit off an occupied people, the latter of which is explicitly illegal under international law.

One group in particular, though, has been leading the charge against SodaStream by calling for a mass, global embargo. The Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) Movement, according to its website, will stand “against Israel until it complies with international law” (i.e. agrees to a two-state solution, ending the occupation of Arab land and creating a Palestinian state) and employs “a strategy that allows people of conscience to play an effective role in the Palestinian struggle for justice.”

Which puts SodaStream squarely in its sights.

In an email to Gizmodo, a BDS spokesperson elaborated on the group’s position:

As set out by the International Committee of the Red Cross, according to international law, as an occupying power Israel is forbidden from altering the occupied territories in any way, including through the construction of settlements and industrial parks, except for reasons having to do with military necessity or to benefit the occupied population specifically.

An at-home countertop carbonator factory is clearly not a military necessity, but whether the factory actually benefits Palestinians is a bit more foggy. To the BDS Movement, that’s a moot point, since displacing Palestinians to make way for Israeli settlements in the first place is in direct violation of the Geneva Convention. The group asserts that “all Israeli settlements built on occupied Palestinian territory are illegal under international law and their construction constitutes a war crime.”

So while SodaStream does supply jobs to Palestinian workers — jobs and salaries that would otherwise be almost wholly nonexistent — the company’s larger role is that of being complicit in a captive Palestinian economy. As Mike Merryman-Lotze, the Palestine-Israel Program Director for the American Friends Service Committee, writes in Al-Jazeera:

The reality is that a self-sustaining Palestinian economy cannot develop under occupation. The Palestinian Authority has no control over either the import of the inputs needed to produce goods or the export of final products. It does not control Palestinian airspace, water and electrical systems, radio frequencies, most natural resources, significant tax revenues, monetary policy, the movement of goods and people inside the occupied Palestinian territories, and many other factors needed to ensure development.

As the “interim” self-governing body of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, the Palestinian Authority’s power over its jurisdiction has been largely nominal. In other words, it has no real control over the Palestinian economy; that task has fallen into Israeli hands — not all to the benefit of the people being occupied. Israeli settlements in the occupied territory have taken land from the Palestinians who once depended on it for an agriculture-based income.

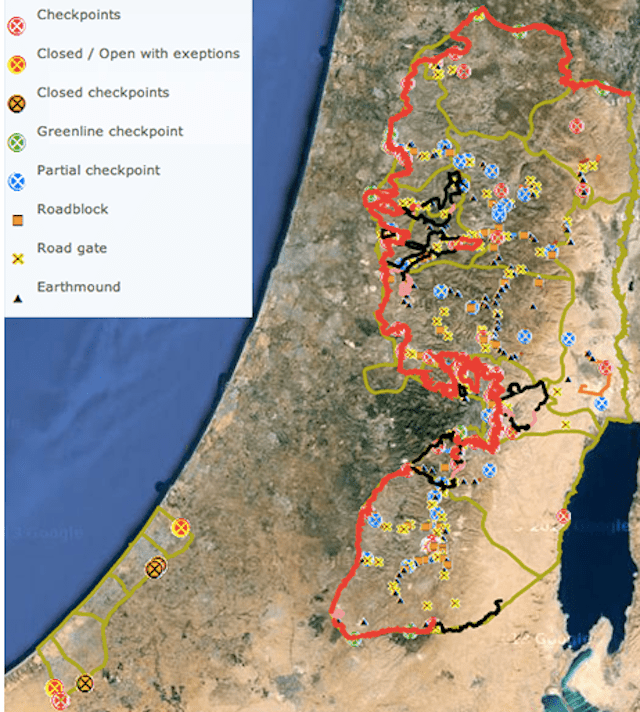

In fact, a recent report from the World Bank found that the Israeli-imposed restrictions in the West Bank alone have cost the Palestinian economy a total of $US3.4 billion dollars a year, or 35 per cent of its total GDP. Within the territory itself, the convoluted web of check points and roadblocks makes it nearly impossible for Palestinians to travel within the Palestinian Territories looking for work.

Instead, Palestinians are forced to look to Israel and Israeli companies for work. Because workforce supply and demand is so out of balance, over half of the jobs available pay less than minimum wage.

In Area C of the West Bank, where the SodaStream factory is located, any sort of development is prohibited without a permit from the Israeli military authority. Permits that, of course, are rarely granted, which futher compounds the issue. So while SodaStream (and companies like it — keep in mind they’re not the only ones taking advantage of the labour opportunity) is indeed granting jobs to people whose only other options might be even less palatable — and despite its apolitical claims — opponents argue that it is being fully complicit in the Israeli occupation of Palestinian land. According to Merryman-Lotze:

By choosing to locate its factory in a settlement, SodaStream has chosen to support the settlement enterprise and the occupation. The taxes the factory pays do not go to benefit Palestinian workers. Rather they go to the Israeli government and the Ma’aleh Adumim Municipality where they are used to support the growth and development of the settlement and to sustain the occupation.

What’s more, the Palestinian population at large doesn’t accept the rationale that giving Palestinians jobs makes up for SodaStream’s complicity in the occupation. In an email to Gizmodo, a BDS spokesperson wrote:

It is obscene for SodaStream to suggest that giving Palestinians jobs in a factory on land that has been stolen from them somehow makes up for its active participation in Israel’s violations of international law. Palestinian civil society rejects any suggestion that the reality that Palestinians are sometimes left with no choice but to work in illegal Israeli settlements is a reason not to take action to end international complicity in human rights violations.

He Said, Stream Said

To hear SodaStream CEO Daniel Birnbaum tell it, what SodaStream has created is in fact a shining respite from an underemployed wasteland, an Eden of diverse cohabitation in which Muslim, Jew, and Christian alike pray in peace — with full medical benefits.

And Birnbaum wants to make sure that everyone is fully aware of just how much of a champion for the Palestinian people he really is, even if it means making an (uncomfortable) public example of Israel’s president himself.

Just a few weeks ago, Birnbaum was set to receive the Outstanding Exporter Award from Shimon Peres. The SodaStream CEO decided to use the opportunity to bring along several of his Palestinian employees, and insisted that he be subjected to the same security measures that were applied to them. When the Palestinian employees were forced to undergo more rigorous, humiliating searches, Birnbaum confronted Peres on stage, embarrassing the Israeli figurehead and forcing a dialogue about basic human rights.

It’s a wonderful thing that Birnbaum stood up for his Palestinian employees. It’s also a savvy public relations move, when taken in the context of the company’s recent posturing. A recent SodaStream — upliftingly titled “Building Bridges, Not Walls” — displays a factory where managerial titles are ripe for the taking by Palestinian employees, and all religious practices are readily accommodated.

Describing his gift to the Palestinian people in the video, Birnbaum gushes:

My hope, my prayer, my belief — and my responsibility at SodaStream is that we will fulfil the prophecy from the book of Isaiah. ‘Nation shall not lift up sword against nation, nor shall they learn war anymore.’ We can make this happen — one person at a time, one family at a time. Instead of learning war, let them learn how to make a soda maker.

The most apt — but also unverified — counterpoint comes from an anonymous Palestinian SodaStream employee who spoke to the Electronic Intifada under the moniker “M.” After being shown the eight-and-a-half minute long video, M. tells the Electronic Intifada:

I feel humiliated and I am also disgraced as a Palestinian, as the claims in this video are all lies. We Palestinian workers in this factory always feel like we are enslaved.

Though the video was conveniently created around the same time that SodaStream boycotts were gaining traction in the U.S., M. describes how the factory workers were told that their participation was a way to help them keep their jobs, since it would increase SodaStream orders. Recalling the guise of a video being filmed for the sole purpose of securing salaries, M. describes how the company leaders “were preparing all the workers and telling them what to say and how to say it. And, despite the video profiling a Palestinian floor manager who worked his way up the ladder, according to M.:

In all of SodaStream, there are only two foremen who are West Bank Palestinians, and they are supervised by two Israeli Arabs.

What about the factory as a mecca of religious freedom? M. describes the “mosque” — highlighted in the video as a room for Muslim prayer — as “just the locker room.” M. goes on to say that the supervisors had “even hidden the carpets from the workers” to prevent them from praying when filming wasn’t taking place. “Those claims [of religious freedom] are all false,” he says. “There is a full discrimination against the [Muslim] workers and we are denied our right to practice our religion.”

It should be noted that M. is an anonymous source, speaking to a staunchly partisan, pro-Palestine publication. That’s not much to go on. But regardless of how accurate his portrayal is, it speaks volumes about how SodaStream is perceived. And it’s that perception that feeds the boycott.

To Boycott or Not

Regardless of where you stand on the issue, there’s no denying that the global boycott is making dents. Just recently, SodaStream stock has dropped about 26 per cent, despite Scarlett Johansson’s high-profile endorsement. So taking a stand, however small it may seem, can make a noticeable difference. Independent of the complex web of issues surrounding SodaStream, it’s validating to know that individual consumers do have that kind of power.

Peter Beinart wrote in The New York Times that “we should support [boycott] efforts because persuading companies and people to begin leaving nondemocratic Israel, instead of continuing to flock there, is crucial to keeping the possibility of a two-state solution alive.” And according to a BDS spokesperson:

A wave of action that began on November 29, the UN International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People, saw actions against retailers that sell SodaStream take place in 50 cities across 6 countries. A number of retailers of in Italy and elsewhere have stopped selling SodaStream following pressure from campaigners.

But no issue is totally black and white. If the current boycott successfully damages SodaStream’s profits, those ultimately most affected will its Palestinian factory workers, who need what little money they might be getting to keep their families afloat.

There are no easy answers, and purchasing a product that may or may not propagate a pre-existing problem doesn’t necessarily make you a bad person. However, it’s a reminder that our purchasing decisions have power, and come with consequences we may never see, whether it’s a blood diamond in an engagement ring, a conflict mineral in a smartphone, or GMOs in our cereal. Or, in this case, the tiny bubbles rising in our water.

Pictures: Top, Bud Korotzer/Adalah-NY; Flickr/Mr. T in DC/Jacob Anikulapo