New documents released by the FBI show that the Bureau is well on its way toward its goal of a fully operational face recognition database by this (northern) summer. EFF received these records in response to our Freedom of Information Act lawsuit for information on Next Generation Identification (NGI) — the FBI’s massive biometric database that may hold records on as much as one third of the US population.

The facial recognition component of this database poses real threats to privacy for all Americans.

What is NGI?

NGI builds on the FBI’s legacy fingerprint database — which already contains well over 100 million individual records — and has been designed to include multiple forms of biometric data, including palm prints and iris scans in addition to fingerprints and face recognition data. NGI combines all these forms of data in each individual’s file, linking them to personal and biographic data like name, home address, ID number, immigration status, age, race, etc. This immense database is shared with other federal agencies and with the approximately 18,000 tribal, state and local law enforcement agencies across the United States.

The records we received show that the face recognition component of NGI may include as many as 52 million face images by 2015. By 2012, NGI already contained 13.6 million images representing between 7 and 8 million individuals, and by the middle of 2013, the size of the database increased to 16 million images. The new records reveal that the database will be capable of processing 55,000 direct photo enrollments daily and of conducting tens of thousands of searches every day.

NGI Will Include Non-Criminal as well as Criminal Photos

One of our biggest concerns about NGI has been the fact that it will include non-criminal as well as criminal face images. We now know that FBI projects that by 2015, the database will include 4.3 million images taken for non-criminal purposes.

Currently, if you apply for any type of job that requires fingerprinting or a background check, your prints are sent to and stored by the FBI in its civil print database. However, the FBI has never before collected a photograph along with those prints. This is changing with NGI. Now an employer could require you to provide a “mug shot” photo along with your fingerprints. If that’s the case, then the FBI will store both your face print and your fingerprints along with your biographic data.

In the past, the FBI has never linked the criminal and non-criminal fingerprint databases. This has meant that any search of the criminal print database (such as to identify a suspect or a latent print at a crime scene) would not touch the non-criminal database. This will also change with NGI. Now every record — whether criminal or non — will have a “Universal Control Number” (UCN), and every search will be run against all records in the database. This means that even if you have never been arrested for a crime, if your employer requires you to submit a photo as part of your background check, your face image could be searched — and you could be implicated as a criminal suspect — just by virtue of having that image in the non-criminal file.

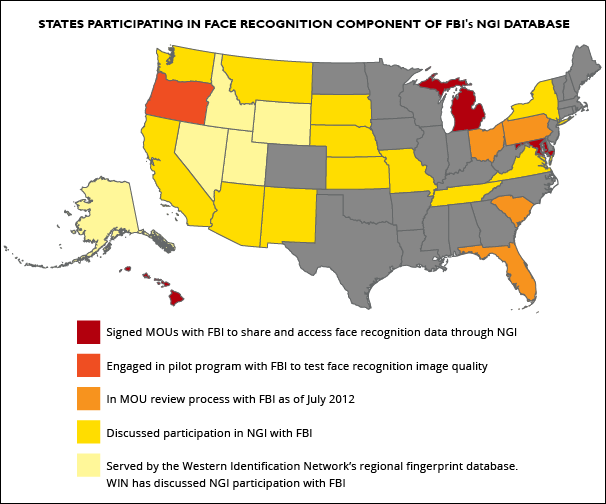

Many States Are Already Participating in NGI

The records detail the many states and law enforcement agencies the FBI has already been working with to build out its database of images (see map below). By 2012, nearly half of U.S. states had at least expressed an interest in participating in the NGI pilot program, and several of those states had already shared their entire criminal mug shot database with the FBI. The FBI hopes to bring all states online with NGI by this year.

The FBI worked particularly closely with Oregon through a special project called “Face Report Card.” The goal of the project was to determine and provide feedback on the quality of the images that states already have in their databases. Through Face Report Card, examiners reviewed 14,408 of Oregon’s face images and found significant problems with image resolution, lighting, background and interference. Examiners also found that the median resolution of images was “well-below” the recommended resolution of .75 megapixels (in comparison, newer iPhone cameras are capable of 8 megapixel resolution).

FBI Disclaims Responsibility for Accuracy

At such a low resolution, it is hard to imagine that identification will be accurate.1 However, the FBI has disclaimed responsibility for accuracy, stating that “[t]he candidate list is an investigative lead not an identification.”

Because the system is designed to provide a ranked list of candidates, the FBI states NGI never actually makes a “positive identification,” and “therefore, there is no false positive rate.” In fact, the FBI only ensures that “the candidate will be returned in the top 50 candidates” 85 per cent of the time “when the true candidate exists in the gallery.”

It is unclear what happens when the “true candidate” does not exist in the gallery — does NGI still return possible matches? Could those people then be subject to criminal investigation for no other reason than that a computer thought their face was mathematically similar to a suspect’s? This doesn’t seem to matter much to the FBI — the Bureau notes that because “this is an investigative search and caveats will be prevalent on the return detailing that the [non-FBI] agency is responsible for determining the identity of the subject, there should be NO legal issues.”

Nearly 1 Million Images Will Come from Unexplained Sources

One of the most curious things to come out of these records is the fact that NGI may include up to 1 million face images in two categories that are not explained anywhere in the documents. According to the FBI, by 2015, NGI may include:

- 46 million criminal images

- 4.3 million civil images

- 215,000 images from the Repository for Individuals of Special Concern (RISC)

- 750,000 images from a “Special Population Cognisant” (SPC) category

- 215,000 images from “New Repositories”

However, the FBI does not define either the “Special Population Cognisant” database or the “new repositories” category. This is a problem because we do not know what rules govern these categories, where the data comes from, how the images are gathered, who has access to them, and whose privacy is impacted.

A 2007 FBI document available on the web describes SPC as “a service provided to Other Federal Organisations (OFOs), or other agencies with special needs by agreement with the FBI” and notes that “[t]hese SPC Files can be specific to a particular case or subject set (e.g., gang or terrorist related), or can be generic agency files consisting of employee records.” If these SPC files and the images in the “new repositories” category are assigned a Universal Control Number along with the rest of the NGI records, then these likely non-criminal records would also be subject to invasive criminal searches.

Government Contractor Responsible for NGI has built some of the Largest Face Recognition Databases in the World

The company responsible for building NGI’s facial recognition component — MorphoTrust(formerly L-1 Identity Solutions) — is also the company that has built the face recognition systems used by approximately 35 state DMVs and many commercial businesses.2MorphoTrust built and maintains the face recognition systems for the Department of State, which has the “largest facial recognition system deployed in the world” with more than 244 million records,3 and for the Department of Defence, which shares its records with the FBI.

The FBI failed to release records discussing whether MorphoTrust uses a standard (likely proprietary) algorithm for its face templates. If it does, it is quite possible that the face templates at each of these disparate agencies could be shared across agencies — raising again the issue that the photograph you thought you were taking just to get a passport or driver’s licence is then searched every time the government is investigating a crime. The FBI seems to be leaning in this direction: an FBI employee email notes that the “best requirements for sending an image in the FR system” include “obtain[ing] DMV version of photo whenever possible.”

Why Should We Care About NGI?

There are several reasons to be concerned about this massive expansion of governmental face recognition data collection. First, as noted above, NGI will allow law enforcement at all levels to search non-criminal and criminal face records at the same time. This means you could become a suspect in a criminal case merely because you applied for a job that required you to submit a photo with your background check.

Second, the FBI and Congress have thus far failed to enact meaningful restrictions on what types of data can be submitted to the system, who can access the data, and how the data can be used. For example, although the FBI has said in these documents that it will not allow non-mug shot photos such as images from social networking sites to be saved to the system, there are no legal or even written FBI policy restrictions in place to prevent this from occurring. As we have stated before, the Privacy Impact Assessment for NGI’s face recognition component hasn’t been updated since 2008, well before the current database was even in development. It cannot therefore address all the privacy issues impacted by NGI.

Finally, even though FBI claims that its ranked candidate list prevents the problem of false positives (someone being falsely identified), this is not the case. A system that only purports to provide the true candidate in the top 50 candidates 85 per cent of the time will return a lot of images of the wrong people. We know from researchers that the risk of false positives increases as the size of the dataset increases — and, at 52 million images, the FBI’s face recognition is a very large dataset. This means that many people will be presented as suspects for crimes they didn’t commit. This is not how our system of justice was designed and should not be a system that Americans tacitly consent to move towards.

For more on our concerns about the increased role of face recognition in criminal and civil contexts, read Jennifer Lynch’s 2012 Senate Testimony. We will continue to monitor the FBI’s expansion of NGI.

Here are the documents:

- FBI NGI Description of Face Recognition Program

- FBI NGI Report Card on Oregon Face Recognition Program

- FBI NGI Sample Memorandum of Understanding with States

- FBI NGI Face Recognition Goals & Objectives

- FBI NGI Information on Implementation

- FBI Emails re. NGI Face Recognition Program

- FBI Emails from Contractors re. NGI

- FBI NGI 2011 Face Recognition Operational Prototype Plan

- FBI NGI Document Discussing Technical Characteristics of Face Recognition Component

- FBI NGI 2010 Face Recognition Trade Study Plan

- FBI NGI Document on L-1’s Commercial Face Recognition Product

1. In fact, another document notes that “since the trend for the quality of data received by the customer is lower and lower quality, specific research and development plans for low quality submission accuracy improvement is highly desirable.”

2. MorphoTrust’s parent company, Safran Morpho, describes itself as “[t]he world leader in biometric systems,” is largely responsible for implementing India’s Aadhaar project, which, ultimately, will collect biometric data from nearly 1.2 billion people.

3. One could argue that Facebook’s is larger. Facebook states that its users have uploaded more than 250 billion photos. However, Facebook never performs face recognition searches on that entire 250 billion photo database.

This article first appeared on Electronic Frontier Foundation and reproduced here under Creative Commons licence.

Picture: Shutterstock