In the United States between 2003 and 2012, one pedestrian was hit by a car every eight minutes. 676,000 of those pedestrians lived. 47,025 of those pedestrians died. That’s 16 times the number of people who were killed by natural disasters like floods, earthquakes or tornadoes during the same period.

A new report by Smart Growth America and the National Complete Streets Coalition called “Dangerous by Design” is full of chilling statistics which prove that pedestrian fatalities are a public health epidemic — one that we’re not doing nearly enough about.

Basically, our streets are killing us.

I know what you’re going to say: Streets don’t kill people — cars kill people. But here’s a crucial fact about cars and pedestrian fatalities in the US: If you’re struck by a car going 20mph (32km/h), you have a 95 per cent chance of living. But if that car is going 40mph (64km/h), your chances of living plummet to 20 per cent. Speed, not cars per se, is what kills.

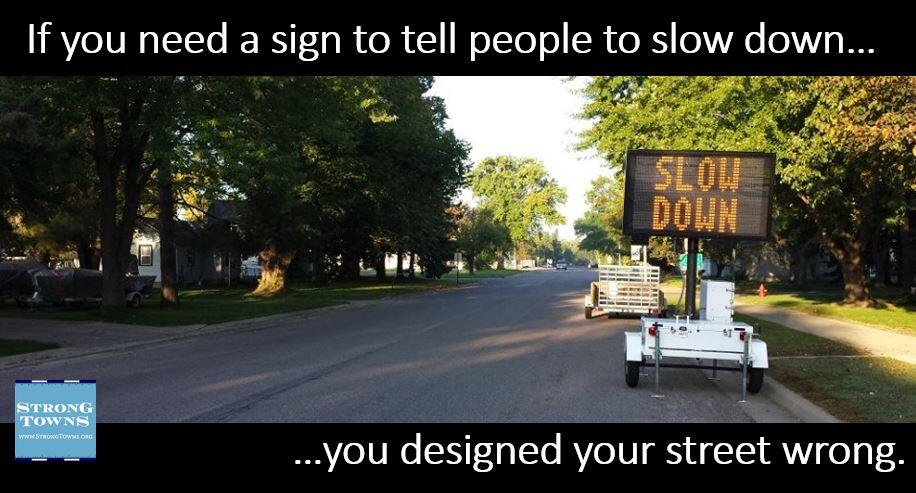

Promotional message by smart growth organisation Strong Towns

The problem in this country is that our streets have historically been designed for speed, to help cars go as fast as possible. Our streets are enabling our vehicles to become death machines. It’s why many cities around the world are lowering their speed limits in their most densely populated areas to 20mph (32km/h).

Ultimately, a “twenty is plenty” mentality will save lives, but it’s not the only solution — nor is it feasible across the board for many cities. What cities need to do is find their deadliest streets and redesign them for pedestrian safety before one more person is killed.

Identifying Mean Streets

How do we find the worst streets in the country? The “Dangerous by Design” report offers one method, rating metropolitan areas with the Pedestrian Danger Index (PDI), which measures how likely a pedestrian is to get struck by a car while walking. The figure is derived from two bits of data: The percentage of people who walk to work and the number of pedestrian fatalities. A high number is bad. The nationwide average is 52.2.

Here are the cities with the highest PDIs. As you read the list, you’ll start to notice the things they have in common (besides, well, Florida).

| 1 | Orlando-Kissimmee, Florida | 244.28 |

| 2 | Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, Florida | 190.13 |

| 3 | Jacksonville, Florida | 182.71 |

| 4 | Miami-Fort Lauderdale- Pompano Beach, Florida | 145.33 |

| 5 | Memphis, Tennessee (including parts of Mississippi and Arkansas) | 131.26 |

| 6 | Birmingham-Hoover, AL | 125.60 |

| 7 | Houston-Sugarland-Baytown, Texas | 119.64 |

| 8 | Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, Georgia | 119.35 |

| 9 | Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, Arizona | 118.64 |

| 10 |

Charlotte-Gastonia-Concord,

North Carolina-South Carolina |

111.74 |

These cities are all in the Sunbelt, a region that saw exceptional urban growth during the age of the automobile. They are largely all cities which developed around a culture of driving, without pedestrians in mind. These streets present deeply engrained design problems, like the lack of crosswalks and sidewalks, which are difficult to fix in a comprehensive way 50 or 60 years after the fact.

According to the report, most fatalities in these places occur on “arterial roads” — those high-capacity roads that aren’t quite freeways although sometimes they are as wide and fast. These are a fact of life in newer, more sprawling communities, but they aren’t the only culprits. Change needs to come block-by-block.

Measuring Safety

So how do we target the deadliest streets for change? A new tool called StreetScore, developed by MIT’s Media Lab, could help.

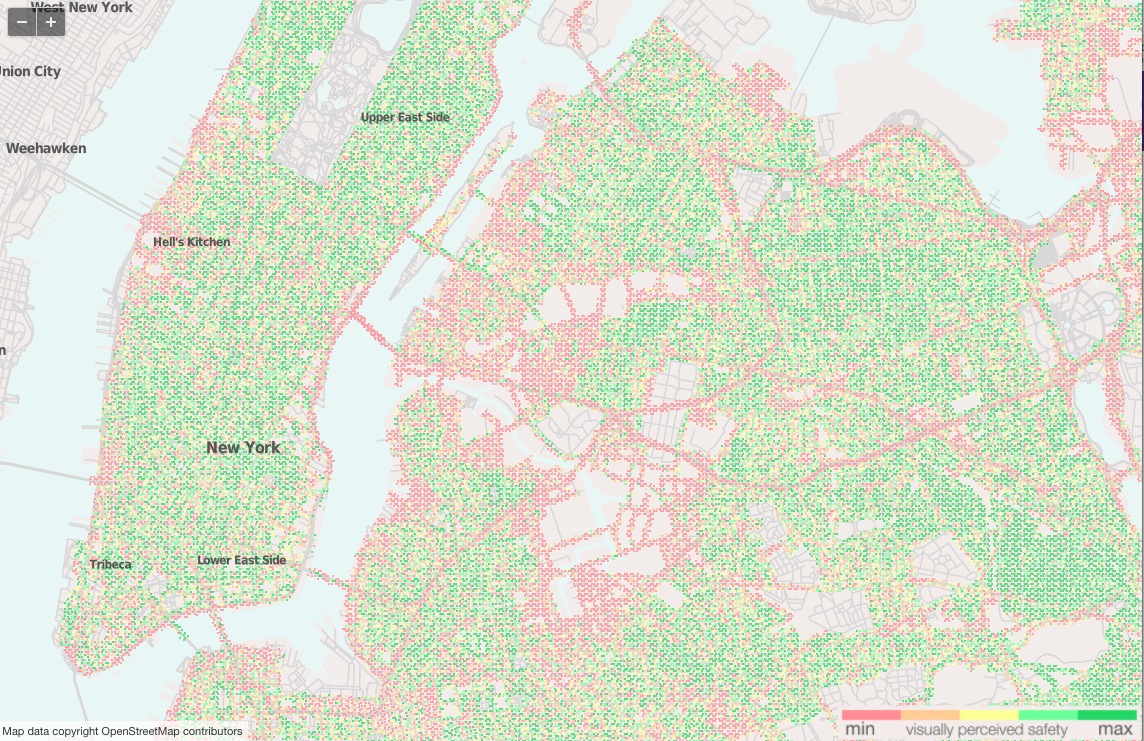

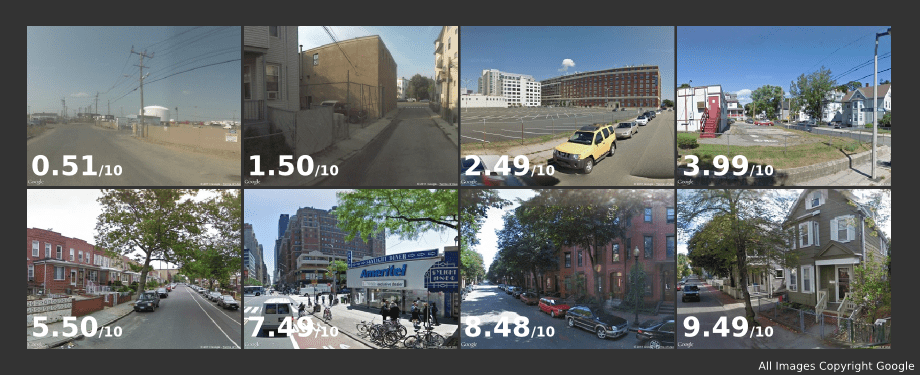

Created as a collaboration between the Macro Connections group and the Camera Culture group, StreetScore measures perceived street safety. Using a machine-learning algorithm, StreetScore can read street-view images, associating certain textures, colours and shapes with safe features. The more of those safe features it spots, the higher the score, with 10 being the max. Above is its map of New York City, the safer streets are green.

As you can see with these images, the ratings seem to correlate with the features we’d associate with safer streets: sidewalks, bike lanes, density. But what’s important about StreetScore is that it measures perception — not, say, crashes which have already occurred. Perception is important because that is what influences the way we drive. Not only does a speed limit change the behaviour of the driver, but certain visual cues like trees, landscaped curbs, street lighting, bike lanes, and the presence of people walking encourage drivers to slow down.

Cities can see where infrastructure changes need to be implemented based on what kind of behaviour a street will encourage.

Google’s Road Diet

Another solution to prevent pedestrian deaths that you might be thinking about, especially in light of Google’s announcement last week: Autonomous cars. Yes, these will help remove the element of driver error — which can’t come soon enough. But autonomous vehicles also signal a larger shift in the way cars move around a city, meaning our ancient grid designed for human-operated cars will quickly become outdated.

Our streets will shrink.

Consider this: With self-driving vehicles there will also be two other major cultural changes: the decline of car ownership, as more people shrug off a personal car for a car-sharing service — why have a car in your garage when one can come to you anytime? — and more efficient traffic flow. Our streets will no longer need to be as wide due to both reduced volume and more intelligent routing.

What self-driving cars will do is help cities implement “road diets,” where planners reduce the number of lanes required for car travel. Streets simply won’t need to be as wide, freeing up more space for larger sidewalks, protected bike lanes, and shade trees — all those good things that make our walks more pleasurable. Our streets will become safer as they become smarter.

A Culture of Fear

The final tier in battling pedestrian deaths is citywide policy that enforces safer streets. Earlier this year, both New York City and San Francisco released Vision Zero plans, which aim to eliminate pedestrian fatalities. While the plans are different, they have similar intentions, including a combination of both improved infrastructure and messaging to place more focus on safety. In New York City, the annual BigApps contest is devoted to producing Vision Zero-related tech solutions, and new legislation passed last week makes it easier to hold drivers accountable for crashes.

A Vision Zero plan should currently be on the desk of every mayor of every city in the U.S. Simple changes could save the lives of hundreds of people. Yet it’s not a priority for cities, many of which — even the ones with Vision Zero plans — are choosing to crack down on the one place they can target and intimidate pedestrians: jaywalking.

Law enforcement is trying to convince walkers they should be scared of the streets, or that crashes are somehow their fault, like this horrible video produced by L.A.’s police department.

“All too often pedestrians and members of our cycling public are seriously injured or killed in collisions involving motor vehicles,” says LAPD Captain John McMahon. “It’s important for downtown Los Angeles residents to know that this is a dense urban environment which can be dangerous to both cyclists and pedestrians.”

Not only does the video position L.A.’s newly vibrant street life as dangerous, 39 seconds in, the video shows a car illegally entering a crosswalk while people are walking with the signal. No wonder pedestrians are in danger — no one is ticketing the vehicles breaking the law!

This is a crucial issue around pedestrian safety where many cities have it backwards. Cities should be focused on decriminalising jaywalking and finding ways to redesign streets that welcome and honour pedestrians, not make them feel like second- or third-class citizens on the roadway hierarchy. In the UK, where there are no jaywalking laws, the rate of pedestrian fatalities are far less than the US.

Streets that are safer for pedestrians are safer for everyone. Redesigning a street, while not always cheap or easy, is the single most effective way to prevent loss of life — saving drivers, cyclists, and pedestrians. How many more people have to die before cities take action?

In New York City this year, pedestrian deaths are on track to exceed the number of homicides, which is a perplexing fact to confront. Statistically, you’re more likely to be hit by a car than a gun. Our streets have unintentionally become more deadly than something explicitly designed to kill.

Picture: April Bertelsen, Portland Bureau of Transportation