As of last week, Buckyballs are dead. The magnetic toy has been officially recalled following a two-year battle with US regulators who sought to ban them. Here’s how a seemingly wonderful amusement became plaything non grata in the span of just a few short years.

A magnetic upstart

Co-founder Jake Bronstein giving a demo during Toy Fair 2011 (Not 2001, despite the video title).

In 2009, Craig Zucker and Jake Bronstein plunked down $US1000 apiece to co-found Maxfield & Oberton, a holding company created to import and market Buckyballs. A standard set of the toy contained 216 extremely powerful little magnets, resembling ball bearings, enclosed in a transparent carrying case case. Unlike common magnets which might be made of an iron alloy, Buckyballs are made of neodymium, a rare earth metal. The powerful attraction between the little balls made them stick together intensely, but with a little practice you could use a set — or two or three sets — to build up some impressive shapes. Buckyballs are insanely addictive, and they were an instant hit with a huge community of enthusiasts who shared photos of their creations online. By the end of the 2009, they were on basically every geeky holiday gift guide.

Unfortunately, young children easily confused the small magnets with candy. After a few hundred thousand units were sold, the United States Consumer Product Safety Commission took notice, as they have in the past with other toys containing magnets.

Buckyballs had initially been labelled for ages 13+; technically, they were never marketed directly to children. But when Congress changed the definition of “children” to anyone under 14, in 2010, Maxfield & Oberton worked with the CSPC to issue a recall. A compromise was reached; the product was still marketed as a toy, the company changed labelling to say to say “Keep away from all children,” and agreed not to sell Buckyballs to kid-focused retailers like Toys “R” Us. And for a few years, that was enough.

Buckyballs grew into a magnetic powerhouse, complete with corporate imitators like Zen Magnets. But behind the warnings and posturing, the health problem hadn’t been resolved. As early as 2011 the commission was issuing strongly worded warnings about Buckyballs. In July of 2012, the CPSC abruptly sued Maxfield & Oberton in an effort to not only get Buckyballs off store shelves, but also to recall the existing product. Despite extensive warnings on the packaging and on the Buckyballs website, the toys were still being swallowed by kids.

The danger

The CPSC recently told the New York Times that since 2009 some 1700 children went to the hospital after swallowing high-powered magnets. Each one of those stories is horrifying.

As it turns out, the powerful magnetic forces that make the balls so much fun to tinker with also make them absurdly dangerous if they end up inside your body. As gastroenterologist Bryan Vartabendian explains on his blog:

When two are ingested they have a way of finding one another. When they catch a loop of intestine, the pressure leads to loss of blood supply, tissue rot, perforation and potentially death.

If that sounds bad, it’s really a very mild, clinical description when compared to the reality. The magnets are powerful enough that if you ingest two balls separately they’re going find each other no matter what, ripping you apart like slow-moving magnetic bullets if necessary to do so.

The news reports are awful. Let’s run down just one to give you a taste for the type of accounts that were landing on the desks of regulators.

On March 4th, 2013, Megan Van Wyk, 6, was rushed to to McMaster Children’s Hospital in Ontario after eating 19 Buckyballs. She told her mother they looked like candy. The Hamilton Spectator Reports:

After three days of supervision with no movement, doctors performed emergency surgery and discovered the magnets had perforated the girl’s small intestine, causing ulcerations in the stomach and leaving two small holes in her bowel.

To say that one more time, as clearly as possible: The attraction between the neodymium balls was so strong that they tore holes in Van Wyk’s internal organs while pulling towards each other.

It was also far from an isolated case. It wasn’t just Megan. It was Sarah, 12, in California who ate four balls; Payton, 3, in Oregon who ate 37 balls; Christin, 14, in Florida who ate two, just to name a few. All of these kids had to have the magnets surgically removed from their bodies.

Parents either didn’t see the warnings or didn’t heed them, and kids were getting hurt. And so in 2012, CPSC stopped cooperating and started demanding, perhaps optimistically, that the magical magnets just go away.

The two year battle

This time, Maxfield & Oberton CEO Craig Zucker refused to roll over. Instead, he launched an aggressive Save Our Balls campaign to try to keep the business alive.

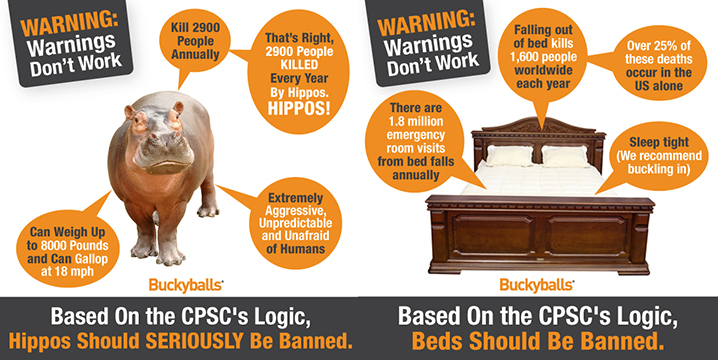

The CPSC’s appeal to children’s health was strong, so Zucker would need to win over public support with an ultra-libertarian view of personal responsibility and government regulation. Not only did Zucker refuse to stop selling his magnets, even as they’d been a proven menace, but he took an antagonistic stance against the government, comparing the dangers of Buckyballs to those of ridiculous targets like hippos and beds. Hippos kill 2900 people a year. 1600 die falling out of bed. Why don’t we ban hippos and beds?

Amusing, sure, but profoundly tone-deaf given the effect his product was having on children. Still, Zucker continued this line of attack in an

interview with Esquire last December:

The CPSC’s argument is that warnings don’t work. If that’s the case, then we need to think of all of the current products on the market that are intended for adults that come with warning labels. Laundry detergent pods, adult-sized ATVs, balloons…

If warnings don’t work — why do we put warning labels on anything?

It didn’t work. Following the CPSC’s action, many retailers stopped carrying Buckyballs, and by the end of the year, just a few months after the initial suit, Maxfield & Oberton was ready to quit the business. (The Save Our Balls website attributed the retreat to CSPC’s “baseless and relentless legal badgering.”) On December 27th, 2012 the company filed a certificate of cancellation in the state of Delaware. They sold off their remaining stock and called it a day.

Total recall

That could have been the end, but the CPSC didn’t just want Buckyballs off of shelves. It wanted to recall the roughly 2.5 million sets that Maxfield & Oberton had sold before going out of business, so in May 2013, they went after Zucker personally, to hold him accountable for the costs of the recall, which it estimated could amount to $US57 million.

Six retailers, including ThinkGeek and Brookstone, voluntarily recalled Buckyballs. But to force more comprehensive action, the commission would need to demonstrate the shakier legal claim that more than simply dangerous, Buckyballs were defective. In which case Zucker wouldn’t just be on the hook for the recall; he could also be personally liable for the injuries Buckyballs were causing. And so again, Zucker and the CPSC went to battle.

“And so it goes…” Thanks to our customers & fans for their support and inspiration. Keep Ballin’. Have fun. Be safe. pic.twitter.com/9F9c4gr0

— Buckyballs (@GetBuckyballs) December 20, 2012

In order to help fund his legal crusade Zucker founded another cutely named organisation called United We Ball, which sold larger Buckyball products that couldn’t be ingested. Its website used lots of fine print to make sure that people didn’t associate it with the disolved Maxwell & Oberton Holdings, LLC.

The case wasn’t put to rest until this past May, when the CPSC settled with Zucker over the recall out of court. The recall would go forward, but Zucker would only be personally liable for $US375,000 in customer refunds. The settlement agreement acknowledges that Zucker never agreed with the CPSC’s assessment over Buckyballs. Additionally, the commission is supposed to stop holding Zucker at all accountable for the defective claim, which has never been demonstrated in court.

Zucker declined to comment to Gizmodo personally, but a representative sent us the following statement:

While the CPSC has continually misstated that the product is defective, both parties signed a consent agreement in the settlement stating that Buckyballs have not been found to present a substantial product hazard or contain a defect. If individuals want to return their Buckyballs via the CPSC-conducted recall, they are entitled to do so.

In short, Zucker needs to make sure everyone knows that he’s not liable for any personal injury claims that might arise. And there are plenty of potential litigants.

Buckyball advocates and even one CSPC commissioner have argued that the CPSC’s actions against Buckyballs were unfair and unprecedented, and that the commission’s settlement with Zucker out of court was something of an admission that perhaps they’d gone further than reasonable in trying to prevent harm to children. Some even suggest that the CSPC’s actions were vindictive, that they went after Zucker personally because he refused to concede to their judgment, and because he spoke out against what he saw as hypocrisy. In fact, just today, the conservative watchdog Cause of Action filed a letter with the Inspector General of the CSPC alleging myriad improprieties on the part of the CSPC.

The biggest open question, though, is just how effective the Buckyballs ban has been. Other manufacturers still sell derivative products, and there are plenty of Buckyball sets still in circulating, still millions of loose magnetic balls sitting in junk drawers. The safest bet, if you still have some lying around? Get rid of them. That little ball bearing pyramid you made just isn’t worth the risk.

Picture: Tom Magliery/Flickr