Art Williams Jr says he never really knew how money worked until he went to prison three times. It’s ironic because Art Williams is also one of the most infamous money counterfeiters in recent American history. And he almost got away with it.

The Chicago native is best known for cracking the 1996 series $US100 bill. That was the design that took American currency into a new era of (somewhat) high tech security. The Feds deemed it unbreakable. But thanks to half a lifetime of experience and an uncanny sense of determination, Williams perfected a process that allowed him to print an infinite supply of almost virtually undetectable bills.

When one of Williams friends emailed me asking if I might be interested in learning about the life of a former counterfeiter, I wanted to know everything about that process. But when Williams and I chatted over the phone, his story was about more than just inkjet printers and razor blades. It’s about the life-changing power plain paper can have, and how it can take you from the streets, to the penthouse apartment, to the inevitable prison cell.

How to make money

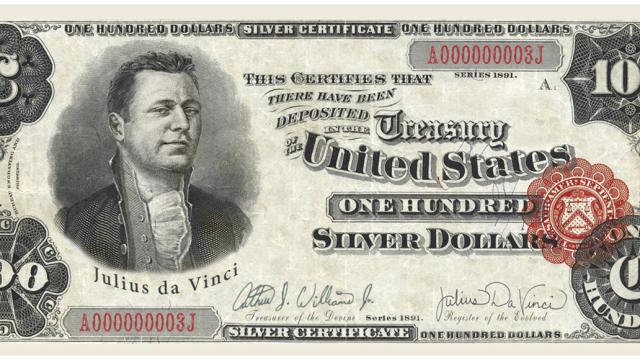

He was born in the comfortable Chicago suburbs, but Williams’ youth took a dark turn when his father abandoned the family and forced his mother to move into a Salvation Army homeless shelter. She would later take up with a local criminal who went by the name “DaVinci.” He earned the nickname for being an excellent drawer and, ultimately, a counterfeiter. Before too long, DaVinci took Williams in as an apprentice and taught him the art of making money with an offset printer.

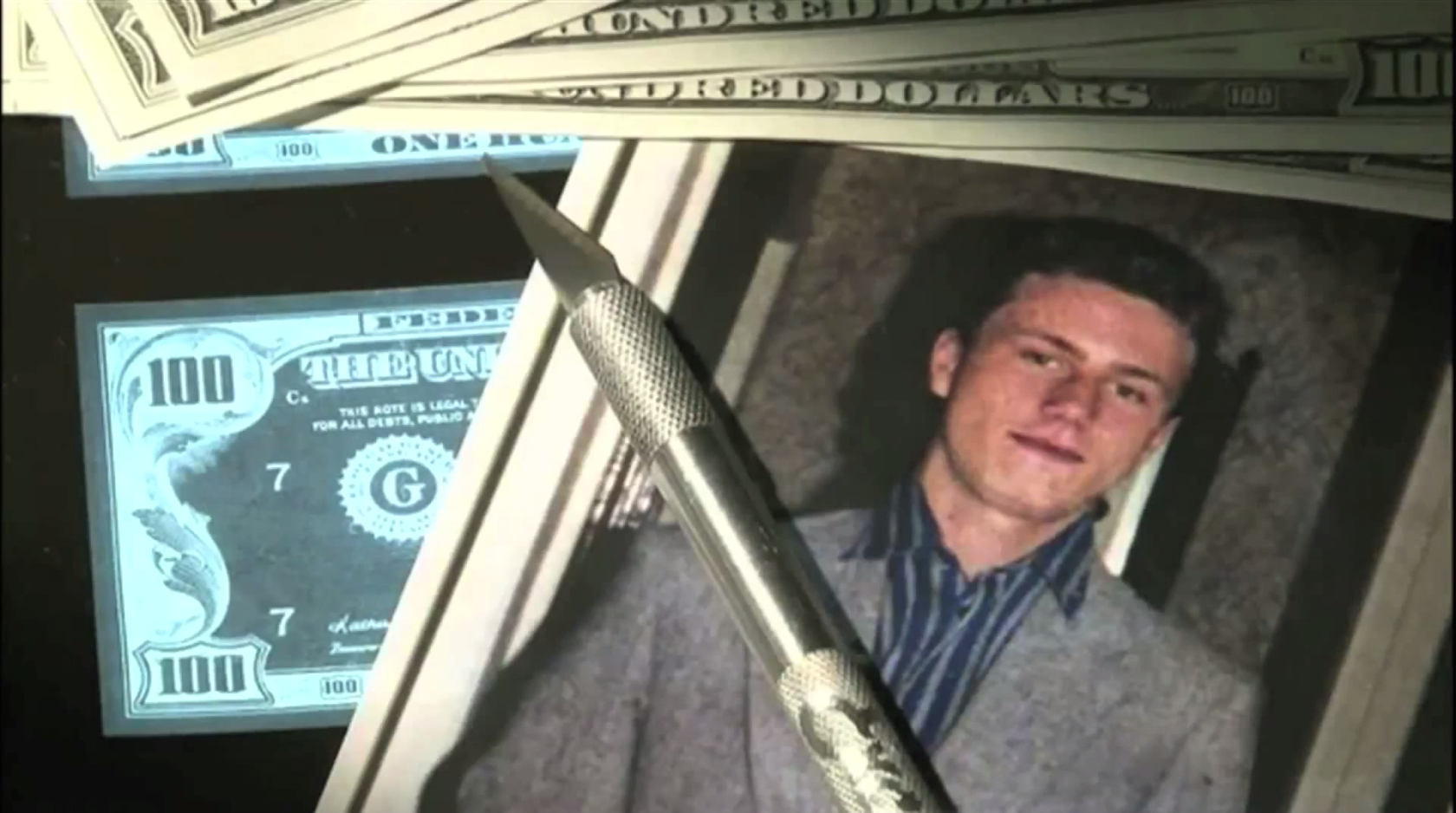

A photograph of Williams at 15 years old, along with a few counterfeiters’ tools.

Williams later described DaVinci as a “pure traditionalist” in an interview with Rolling Stone. “In those days, counterfeiting was something that was handed down through generations,” he said. “He told me I was one of the last apprentices. I took the knowledge he gave me and I amplified it.”

Eventually, Williams perfected his own method of so-called “hybrid” counterfeiting. It started in 1992, when the young student got his hands on a bootleg copy of Adobe Photoshop, an old Apple, and a diazotope blueprint machine. Since the blueprint printer couldn’t reproduce the green background of real money, he’d run the paper through an offset printer first, and then print the Photoshopped details onto the tinted paper with the high tech printer. According to Rolling Stone, he was printing about $US50,000 a month in a basement studio dubbed “The Dungeon” and selling them to local gangsters for 20-cents on the dollar. He also lived like a king in the meantime.

It was an improvement over the small time burglary jobs that he’d once done. But in retrospect, there was no escape from a life of crime. “I tried to run from the streets,” Williams told me, “but unfortunately the streets were already in me.”

Faking it the right way

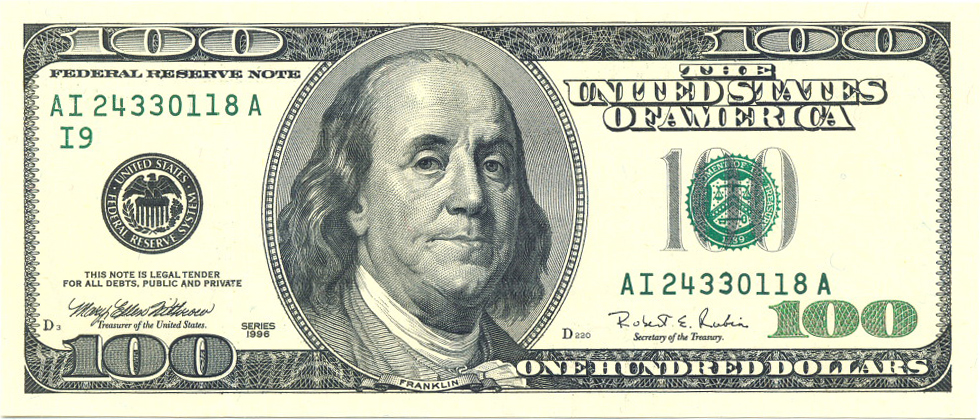

Williams stayed pretty small-time until 1996, when the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing announced a new, super secure $US100 bill. The old Benjamins largely relied on the unique weight and feel of its special 75-per cent cotton, 25-per cent linen paper stock, but the new $US100 bill introduced a new fluorescent security thread, micro-printing, colour-shifting ink, and watermark that was difficult — nigh impossible — to duplicate. When his girlfriend joked that he couldn’t crack the security, Williams took it as a challenge.

The most important part, it turns out, was finding the right kind of paper. Along with the 1996 series bills’s new security measures came the introduction of the counterfeit detection pen. You’ve surely seen the pen’s iodine-based ink in action. When you mark a bill, the ink will turn brown if the paper contains starch — as almost all counterfeit paper does. If it stays yellow, that means the paper is authentic, in theory at least. But Williams didn’t need to find genuine currency paper. He just needed to find a starch-free substitute.

A Series 1996 $US100 bill. The green “100” in the lower-right turns black when viewed from a different angle.

“It was kind of a freak accident actually,” Williams told me. “It wasn’t anything intelligent.” In a moment of frustration, after trying and failing to find a match among countless paper samples, his girlfriend started marking every piece of paper in the house. Of all things — toilet paper, card stock, printer paper — it was actually the phonebook that marked correctly. Directory paper, a form of newsprint, was the key.

The only problem was that directory paper was too thin. To solve this problem, Williams would simply glue two pieces of the starch free paper to a piece of thicker paper to create a sort of counterfeit sandwich. This also made it easy to embed homemade security strips and fake a watermark on each bill. In order to beat the colour-shifting ink problem, the Williams made a “100” rubber stamp at Kinko’s and used iridescent car paint to create a similar effect. The final security measure, microprinting, was difficult to reproduce perfectly, but luckily, it was also the measure people checked least often, since you needed a magnifying glass to tell the difference.

The subtle skill of spending

In the end, changing the serial numbers on the bills proved to be the most dangerous part of the process. All bills eventually flow back to a bank, and the banks send them to the Federal Reserve which uses a 13-point check system to spot batches of counterfeit bills. However, Williams figured out that if he spent only a few bills at a time and moved around the country constantly, he’d be sheltered enough. And for the most part, he was right.

For a while, Williams and his girlfriend traveled around the country, mostly splitting their time between the Chicagoland area and Texas, spending as much money as they could. As counterfeiters do, they’d make small purchases with a $US100 bill, and then pocket the (real) change as profit. Williams would also unload sell batches of counterfeit bills to local gangsters like he used to but for a higher rate: about 30 cents on the dollar. He used a whole slew of tricks to stay off the police radar. “I as a real gadget guy,” Williams told me. “I was kind of like James Bond in a way.”

Williams posing with a Mustang that he bought about a year before his 2001 arrest in Alaska.

In the late 90s, millions of dollars passed through Williams’ press and inkjet printer. He couldn’t spend it fast enough. At one point, he and his girlfriend started buying toys and things for kids and just donating it all to local charities. It wasn’t so much the spending that was intoxicating, though. It was the challenge of turning each single piece of paper into one hundred US dollars. “Seeing a piece of blank paper as a canvas, and knowing it’d be a legitimate piece of currency by the time I was done with it, was the biggest thrill for me,” Williams said. He added, “I slowly started to lose myself.”

It all hit the fan in February of 2001, when Williams was caught with $US60,000 in counterfeit bills, drugs, and his wife’s naked sister in a Chicago hotel room. That bust should have sent him to jail for a very long time, but the judge let him walk due to an illegal search and seizure. Still sweating from the close call, Williams decided to get out of the game. Or at least to try.

Giving it all away

It was a good decision, but it didn’t last for long. Soon after his close call, Williams then found out that his father, who’d had his own trouble with the law, was living in Alaska. When he went to visit, the younger Williams learned that his father had been growing weed and had run into some trouble with the Hell’s Angels. Rather than help his son stay straight, his father encouraged Williams to make more money. “I had my father back,” he said. “I wanted to make him proud.”

In Alaska, William’s began printing money again, but without the proper equipment this time. The elder Williams gave it away to his friends, who spent it freely, ignorant of the proper ways to unload counterfeit bills. Williams himself continued to travel, stashing some exceptional batches of cash into PVC pipes, and buried them in a forest reserve. But of course, the sloppiness in Alaska came back to haunt him.

In 2001, some family friends were arrested with counterfeit money in Anchorage. It didn’t take long for wiretaps to bust Williams and his father, who both went to prison. After 31 months, the younger Williams was released, only to learn on the car ride home that his father had died of a heart attack in his cell that same morning. The news sent Williams spiraling into grief and, eventually, towards an effort to reconnect with his own son, who dreamed about a music career.

Williams says he became a celebrity of sorts in prison after being featured in a 2011 episode of American Greed.

Once on the outside, Williams’ story attracted a lot of attention, including the 2005 feature in Rolling Stone. While making public appearances to talk about going to prison for counterfeiting, though, Williams ended up digging up the money in the PVC pipes and even printing more to fund his son’s quest. He even started researching again, since the Russian gangs that used to buy big batches of his bills were more interested in the Euro. “Here I am doing speaking engagements talking about counterfeit money,” he said, “and I’m trying to crack the Euro at the same time.”

Williams told me that he was frighteningly close doing it, too. The holographic strip was the tough part, but when he was experimenting with the same material used in baseball cards in 2007, Williams caught his son making counterfeiting money on an inkjet printer. A fight ensued, and it spilled onto the street, ending with a flourish of angrily thrown counterfeit bills.

Williams went away for six-and-a-half years that time. His son was later busted for trying to counterfeit and ended up in the same prison in 2010.

Making it the right way

Upon leaving prison in January, Williams got right to work. This time he stayed away from the printing presses and found a job as a janitor. And for Williams, going from toting duffel bags full of cash one year to scrubbing a toilet for $US5-an-hour a few years later was one hell of a change. “I didn’t have any respect for money [before],” Williams explained. After all, he’d spent most of his life literally printing money.

But things have turned out pretty alright for Williams. He’s not drowning in cash any more, but the former criminal — now in his early 40s — transports exotic cars for a living. When he’s not driving Ferraris, Williams is working on becoming an entrepreneur. He’s been busy trying to fire up a clothing line called Julius DaVinci. The name, of course, is borrowed from his original counterfeiting teacher, and the aesthetic borrows from the art that Williams created while in prison.

You might call the style a sort of Federal Reserve chic, with symbols borrowed from U.S. currency and hat tips toward the Medici legend. Williams also plans to publish a book of fiction, Cain’s Dagger, this fall. Meanwhile, a documentary about Williams’ life after prison is nearing completion. Of course, Williams can’t make money directly from chronicling his crimes, but enough of his projects lie on the periphery that his small empire of creative projects will certainly benefit from the exposure the former counterfeiter’s enjoyed lately.

The reel for Sizzle, a documentary by Dominic Nguyen about Williams’ life after prison

The whole saga sounds like a hell of a movie. In fact, Jason Kersten expanded his Rolling Stone article about Williams into a book that was optioned by Paramount Pictures. Rumour has it that actor Chris Pine of Star Trek fame will play Williams. Depending on if and when the movie makes it to the screen, how his own book does, and the success of Julius DaVinci, it’s entirely possible that Williams could get rich all over again. But, you know, in a more legit sort of way. In the meantime, Williams says he also figured out how smartphones work, a common challenge for folks who spent time in the slammer.

Throughout his whole Hollywood-friendly adventure, Williams has learned how money works on so many levels. Not only does he understand the mechanics of the printed currency itself, he also knows how it moves around the country, fueling markets of all kinds. Williams also learned the worth of a hard day’s work at minimum wage. His attitude still seems somehow street smart. In Williams’ own words, “You need money to make things happen.” And even if you can just print it, it probably pays to find another way.

All images courtesy of Arthur Williams Jr / Dominic Nguyen. The top image depicts a fictitious Julius DaVinci, who looks not unlike Williams himself.