Yesterday a 91-year-old former executive at the baseball card company Topps passed away in Long Island. You might not know Sy Berger’s name, but he was the person who turned baseball cards into a phenomenon — and, in some ways, defined baseball fandom. And he did it with design.

Baseball cards go back to the 19th century, but they weren’t like the cards you traded as a kid. These were tepid, monochromatic paper cards where you might find a photo of a ballplayer, but probably no stats, nicknames or detailed information. So how did the modern baseball card emerge? Why did bits of cardboard with player’s names and images suddenly explode in the years after World War II, instead of any number of other toys on the market?

It turns out, the development of modern cards wasn’t exactly spurred by the fans — it was spurred by a booming Brooklyn candy company and one of its brilliant employees, Sy Berger.

A Sugary Sales Ploy

Berger was a New Yorker: He was born in Manhattan and studied accounting, and after World War II, went to work for a company called Topps Chewing Gum, Inc. Topps is a Brooklyn company owned by four brothers which had, in the 1800s, started out as a tobacco company. In the 1930s, it had renamed itself and gone into the gum business — Bazooka was one of its first hits, and it sold hard chunks of the stuff with wrapper comics.

Baseball cards had been used to sell everything from cigarettes to “Post Toasties, Num Num Potato Chips and Red Heart Dog Food,” according to this great 1981 Sports Illustrated story. But candy seemed to hit just the right balance between the sugar and the sport for young fans, and the fact that confectioners could mould it to fit the size of the cards themselves was a major bonus. So in 1951, Berger decided to put out a pack of cards that let kids “play” a game of baseball. Each of Berger’s cards had a player and his name along with an action, like a strike or a foul ball. But the cards were sold with taffy, and according to The New York Times, the taffy was disgusting disaster — because it “wound up picking up the flavour of the varnish on the cards.” Despite that — or maybe because of it — the cards are valuable collector’s items today.

Even Berger, then in his late 20s and pretty much winging it, knew it was a “disaster.” But the following year, he tried again — and struck what you might describe as pink gold. In the fantastic Mint Condition: How Baseball Cards Became an American Obsession, author David Jamieson explains how Berger leveraged design to build a card so successful that it would, eventually, be the subject of lawsuits alleging a monopoly on the business.

The Numbers Game

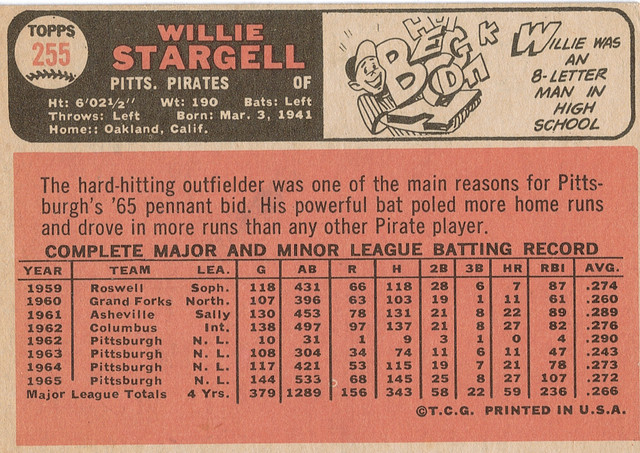

Berger and his collaborators developed their card around the table of his apartment in Brownsville, Brooklyn, during late-night design sessions. “The card they ended up developing included a number of features that rarely, if ever, turned up on earlier sports cards,” Jamieson writes. They included details like player autographs, team logos, and nicknames. They created a totally new design for the back of the cards, too:

As a youngster, Berger, the accountant, had been obsessed with computing his favourite players’ averages over the newspaper at the breakfast table. He thought that children might enjoy reading each player’s statistics in a more kid-friendly format.

So he created a page of stats about each player, including career highlights, that would usher in the now-familiar era of numbers-obsessed baseball.

Kids might have known their favourite ballplayers and their biggest wins before that, but Berger’s stats changed how young fans talked about and understood the game. As Sports Illustrated’s Jamal Green explained in 2000:

Kids across America suddenly could recite stats and recognise uniforms. They would learn nicknames like Choo Choo (Coleman) and how to spell Yastrzemski. They would revel in mistakes made by Topps: Hank Aaron batting as a lefty in 1957, Gino Cimoli swinging an invisible bat in ’58 and the ’69 Aurelio Rodriguez card that pictured a batboy, not Rodriguez.

Up until then, kids would need to dig through the papers to learn the current stats of their favourites. Berger tied the numbers to the players, and in doing so, created a phenomenon that introduced kids to the numbers behind their favourite game.

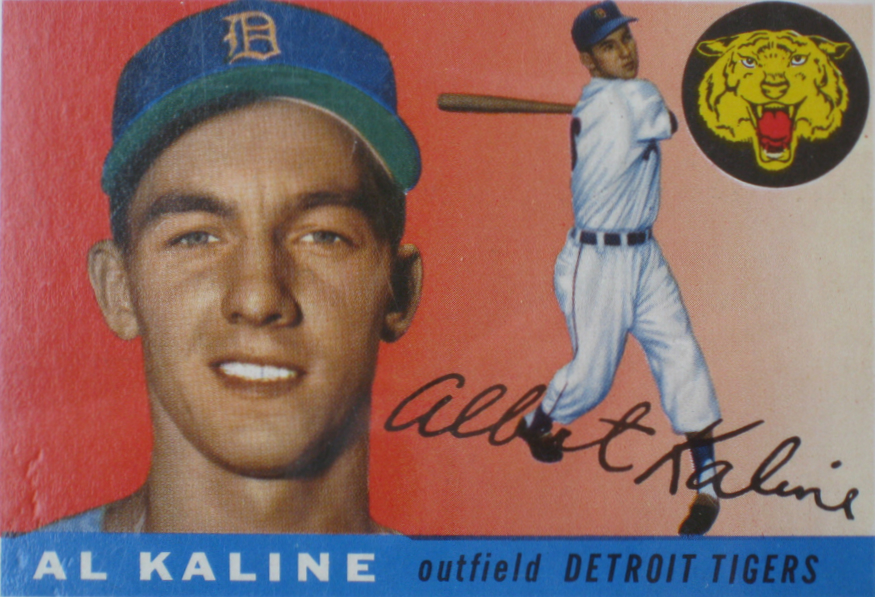

Another big part of Berger’s job was signing the players themselves — which he excelled at, offering cash or cards in exchange for exclusive signing rights. Some players were embarrassed or nervous to pose for the hero-shot photographs that would accompany their cards, as Al Kaline, pictured above, recalled to Franz Lidz recounted in 1981:

“I used to be embarrassed to go out and pose,” recalls Al Kaline. “They always got me before games on the road, and the fans would be yelling,’Hey, Kaline, you bum.’ I’d ask the photographer to use the card from the year before. Hell, I was on 21 of them.”

The Garbage Truck of Fate

The cards Berger designed around his table during those late-night sessions in the 1950s ended up becoming hugely influential in baseball culture, both in terms of how young fans got into the sport and how they understood that impact of stats. And his baseball card culture was the model for countless other toy franchises, from Pokemon cards to Pogs.

Still, Berger didn’t imagine the empire that he was building in those early years would turn into a multimillion-dollar collector’s market. Maybe one of the most famous anecdotes — and one recounted in nearly every obituary yesterday — about his work details an incident that illustrates just how unforeseen the baseball card market was.

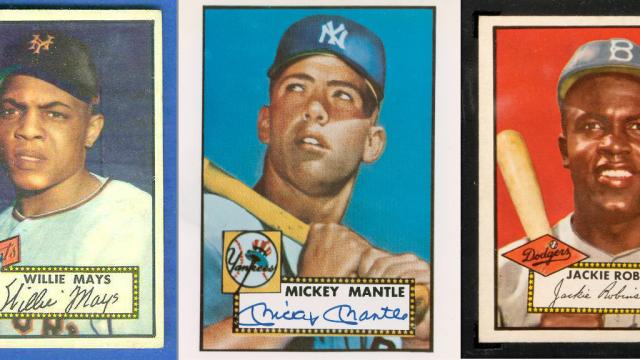

In an story recounted in Mint Condition, we learn that Topps printed a series of late-season cards that featured future greats like Micky Mantle and Jackie Robinson in 1952. The cards didn’t sell terribly well, and in the 1960s, Berger had tons of the cards leftover. As Jamieson explains, Berger could find no buyers and didn’t want the old coupons inside the packs to find their way to purchasers. So instead of trashing them, he loaded up three whole garbage trucks and put them on a garbage boat leaving from Brooklyn — then dumped the remaining 1952 stock out at sea.

Incredibly, Mantle’s card from that year recently sold at auction for $US130,000. It’s impossible to say how many other $US130,000 cards were dumped into the Atlantic, thin cardboard disintegrating within days, somewhere off the coast of New Jersey.