“He was wearing all cotton, which is the worst fabric for cold, wet weather. The weather just got the best of him,” reads an official statement by the Alaska State Troopers about the death of a hiker there in 2005. This is how and why cotton can kill you.

Hypothermia

The Mayo Clinic definition reads: “Hypothermia is a medical emergency that occurs when your body loses heat faster than it can produce heat, causing a dangerously low body temperature. Normal body temperature is around 37C. Hypothermia (hi-poe-THUR-me-uh) occurs as your body temperature passes below 35C.”

Over 1500 people in the US die from hypothermia each year. It causes a variety of things in your body to stop working, but the most important seems to be your heart. It will stop if your core temperature drops too low.

So you only have to worry about it in sub-freezing temperature right? Wrong. While cold conditions will effect us all differently depending on our general health, physical fitness and other factors like genetics, the hypothermia can be experienced in surprisingly warm weather. For instance, the Mayo Clinic warns that elderly persons may be subject to hypothermia, “…in an air-conditioned home.”

Hikers are more likely to die of hypothermia in the spring, summer and fall than they are in the winter; during those months the odds that they will be caught unprepared are simply higher.

And, the Mayo Clinic also specifically cautions against wearing cotton, saying, “Wool, silk or polypropylene inner layers hold body heat better than cotton does.”

Cotton And Water

Cotton garments can absorb up to 27 times their weight in water, something which means they a) take forever to dry out and b) actively work to cool your body in even moderate temperatures.

And you can get cotton wet without exposing it to rain or submersion. Sweat heavily in it and it will soak up that sweat and hang onto it, which can lead to any of the problems described in this article as easily as falling into a lake will.

Why is cotton so absorbent? According to the Appalachian Mountain Club:

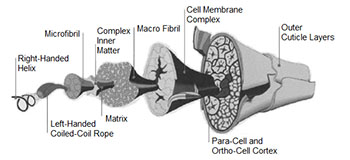

“A cotton fibre is like a tiny tube formed of six different concentric layers. As individual cotton fibres grow on the plant, the inside of the “tube” is filled with living cells. Once the fibre matures and the cotton boll opens up to reveal its puffy white contents, these cells dry up and the fibre partially collapses, leaving behind a hollow bean-shaped canal, or ‘lumen’ (see the ultra-magnified image below). This empty space holds lots of water.”

“Processed cotton fibres are 99 per cent cellulose. Cellulose is a polymer composed of a long chain of connected glucose molecules that each contains three hyrodoxol groups with slight negative charges. Water, as you may remember from high school chemistry, has a slightly positive charge (the oxygen atom draws in the two hydrogen atoms’ electrons). The upshot is that water molecules are attracted to — and bond with (via hydrogen bonds) — the zillions of hydroxol groups in cotton. This, coupled with the vast amount of space contained within and between the fibres, provides cotton with its tremendous water-absorbing properties.”

Cotton traps water inside its fibres, which is why it takes so long to dry out.

Why Being Wet Is A Problem

According to the United States Search and Rescue Task Force, “Water conducts heat away from the body 25 times faster than air because it has a greater density (therefore a greater heat capacity). Stay dry = stay alive!”

Getting wet and staying wet, even in above-freezing temperatures can rapidly cool your body as a result.

And, by filling up with water, an insulating cotton garment such as a hoody loses the trapped air space that made it warm when it was dry. This exposes you more significantly to simple radiant heat loss, where the shear difference in temperature between your body and the environment causes you to get colder.

You’ll also be more subject to evaporative heat loss as water slowly leaves the cotton garment, something exacerbated by wind chill.

All together, getting wet and staying wet outdoors is simply a recipe for disaster.

How Other Fabrics Keep You Warm When They’re Wet

Wool: The outer layer of each wool fibre is a filmy skin called an epicuticle. This coating repels water drops, preventing it from soaking through the fibres. Due to the fuzzy nature of wool fabrics, rain droplets are less likely to break up, instead beading on the surface and running off. When water is in vapour form from humidity or sweat, it can pass through the epicuticle and be absorbed into the wool fibre; each fibre can absorb up to 37 per cent of its weight without feeling wet. And finally, the “crimp” or kinkiness of the wool fibres also builds dead air space into any wool garment, providing insulation even when wet. http://indefinitelywild.gizmodo.com/how-to-stay-wa…

Polyester: Polyester fibres are the basis of many garments and insulating materials, including Polarfleece, Primaloft, Capilene, microfibers and anything similar. Polyester fibres do not absorb any water. At a minimum that means materials made from them will dry more quickly than cotton. Most garments made from polyester are designed to insulate while wet by retaining trapped air and many are designed to actively shed moisture through the shape or arrangement of their fibres.

Nylon: Similar to polyester in that its fibres are created from petroleum, nylon is also used to make “fleece” insulating garments. While nylon fibres can absorb some water, its saturation rate (dependent on which type of thread is used) never exceeds 10 per cent and it lacks the polarity issues of cotton. Thanks to the lack of molecular bonding and the small amount of water absorbed, Nylon dries very quickly and, similar to polyester, fabrics made from it can be designed to retain trapped air when wet, keeping them warm.

Rayon, Viscose, Tencel, Lyocell, Bamboo and Silk: Silk can retain up to 30 per cent of its weight in water and will lose most of its insulation when it does. Other materials listed here as essentially artificial silk made from cellulose. Not only do they absorb water, but they have the same molecular bonding issues described for cotton above.

So What Do You Wear?

It’s fairly easy to ditch cotton on the top half of your body. Your best option is to swap a cotton t-shirt for one made from an appropriate weight of merino wool. Merino is a wonder material that helps keep you cool when its hot and warm when it’s cold, while wicking water away from your skin to keep you dry. Yes, t-shirts made from it are more expensive than their cotton equivalents, but they will also last longer, won’t stink after you sweat in them and, well, won’t kill you through hypothermia. You can find merino in weights appropriate for the hottest desert conditions on down to stuff designed for the coldest winters. It’s an excellent fabric to be active in.

Insulation layers are also easily replaced. There’s very few things that are warmer or more versatile than a wool sweater and mid-layers made from fleece are insanely good value while being very warm.

The hardest item of cotton to ditch is going to be your jeans. Nothing is more of a staple in the western wardrobe and jeans manage to be both fashionable and rugged, all factors that make it easy to just say “f**k it” and wear them to do stuff outdoors. But, even in warm summer conditions, you’ll be better off in a pair of synthetic trousers, which will breathe better, wear cooler and won’t soak up water from sweat or a stream crossing.

For pants that replicate much of the look and versatility of jeans, but are practical and comfortable for use outdoors, we recommend the Lululemon ABC Pant ($US128) which combines solid casual style with a wicking, four-way stretch material for movement and comfort. Those are great for warmer weather while the Makers and Riders Commuter Jean ($US169), which combines a waterproof, four-way stretch material with a jeans-alike cut and look is a great option for colder or wetter conditions.

There’s plenty of cheaper options out there if you don’t mind looking like the type of person who values the ability to convert their pants to shorts by just zipping them off. Any material but cotton is going to work better at everything, especially at not killing you.

Pictures: Texas 713, Chris Brinlee Jr