If you turned on the Cardinals v Nationals game last night, you witnessed the first live broadcast of Major League Baseball’s awesome new player tracking and statistics system. This is Statcast: The incredibly fast, incredibly detailed art of playing baseball, broken down into easy to digest metrics that make sense. Hell yeah.

Here’s the first in-game Statcast. It’s shows the velocity and spin details of the nasty Gio Gonzalez pitch that got Jhonny Peralta swinging in the first inning. It didn’t run until after Gonzalez’s struck out Mark Reynolds at the beginning of the second inning:

MLB’s embeds don’t play nice in Kinja so if you wanna pause, hit space.

Statcast is now fully deployed across the 30 major league parks. It tracks data on every play, and crunches the numbers into fast analytics presented in easy to read graphics for the viewer at home.

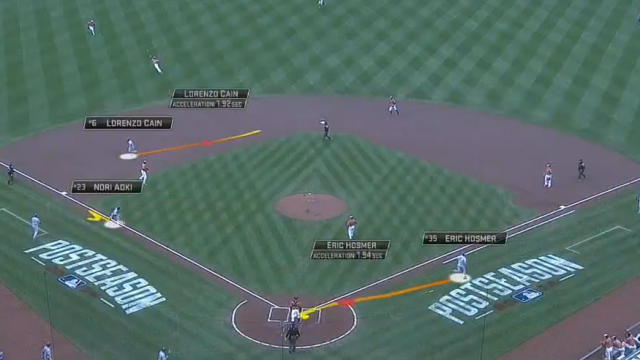

If you’re a fan, you’ve probably seen tests of the player tracking tech creep into broadcasts over the last year — MLB likes to showcase it with this amazing double play from the 2014 Giants v Royals World Series, and I gotta hand it to them it’s an incredibly detailed breakdown of a phenomenal play that has lots of different components to it. (And way more sophisticated than what can be pulled off in real time.) Have a watch:

MLB’s embeds don’t play nice in Kinja so if you wanna pause, hit space.

Holy shit! I remember watching that play last year, and it’s amazing on a number of levels: Joe Panik’s diving stop at second is stunning; Brandon Crawford’s catch and quick turn to throw the ball to first is fantastic. But what I didn’t focus on at first was how boneheaded Eric Hosmer’s slide into first was. He slid, and he was out. Had he run through the bag the way he’d been taught to his entire life, he would have been safe. By sliding he’s out by fractions of a second. If he’d run through the bag, he’d have been safe by fractions.

The data captured will be used in both game broadcasts and given to clubs to use to track player performance. As a fan, I’m most interested in how this is going to change the way I watch the game, so I’ll focus on that aspect. (Although, if the Orioles can use it to figure out how to build a starting rotation that works, I’ll be much obliged.)

Starting last night, viewers will see graphical breakdown of stats like perceived velocity and spin rate for pitching; projected home run distance, exit velocity, and launch angle for hitting; lead distance and first step time for baserunning; and first step time, acceleration, speed, and route efficiency. Over time, more will be added to the Statcast live repertoire.

Sound dull and tedious? Welcome to baseball! More than any other sport, baseball is all about numbers. The sport is very slow, and the moments that matter happen almost too fast to see. Stats and numbers make the action you can’t see understandable — and enjoyable.

You can compare it to MLB Advanced Media’s pitch tracking technology, which was introduced a decade ago. It revolutionised how we watch the sport by demystifying pitching. Even on TV you can’t really see what a pitch is doing as it approaches a batter, and pitch tracking finally gave more casual watchers a way to understand just how complex the mechanics of pitching and hitting are.

Defensive plays are some of the most exciting and important plays in baseball, but unlike pitching and hitting, we’ve never been able to quantify them meaningfully. Until now.

MLB media brass are particularly proud of the route efficiency metric they developed. The metric shows how close to a perfect route a fielder ran to make a play. In the video below, Statcast breaks down one of the best plays of the season so far by Kevin Pillar, who robs a home run with a route efficiency of 97.1 per cent:

MLB’s embeds don’t play nice in Kinja so if you wanna pause, hit space.

It’s a derivative metric, unlike say, first-step time, which with the right told you can objectively measure. “It really speaks to people,” MLB.com CTO Joe Inzerillo told me in an interview about the tech behind Statcast.

According to Inzerillo, the idea for Statcast-like tracking of players on the field was first conceived back around the time that Pitch tracking was first developed but it’s only been technologically possible for the past few years. What specific tech needed to advance to make it possible? It was announced last year at the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, and in just over a year, MLB has been able to make the system viable for instant replays.

Here’s how the MLB made an analytics fantasy real from one season to the next.

How it works

Statcast is currently in every ballpark, capturing data about every play. MLB’s embeds don’t play nice in Kinja so if you wanna pause, hit space.

The system uses two main sensor inputs two create its stunningly precise analytics: Radar and optical cameras. A Doppler radar panel is mounted behind home plate, and takes readings of the field at the rate of 2000 samples per second. The stereoscopic camera array consists of two 5k resolution cameras mounted 15 feet apart back behind third base.

The two optical images are stitched together into a single image, and the parallax between the cameras is used to precisely calculate the player distances. Radar technology, as you probably know, works by shooting out imperceptible electromagnetic signals, and measuring how much time it takes them to come back. Doppler radar calculates velocity information by listening to how the frequency f the signal has changed.

The optical and radar systems have different advantages. The radar is used primarily for tracking the ball, while the optical system is particularly good for player tracking.

The overall process goes like this: A human operator signals the beginning or end of a play because Statcast can’t read umpire signals. As the play happens, data is collected by both the radar and the cameras. The raw data gets a little bit of processing on computers next to the sensors themselves, but then its kicked back to a central computer on site, where a lot of the instantaneous graphics and stats you’ll see while watching a broadcast will be assembled. The data is also sent up to the cloud, where it’s crunched for more complicated stat-tracking, like leaderboards and running season stats.

A large part of the development process wasn’t just getting the systems to calculate the data correctly, but to do the groundwork to ensure that the data collected was accurate. Much of what caused hours or even days of delay in producing the striking Statcast replay reels was verification. MLB wanted to ensure that the metrics were absolutely right.

The human operator can help verify the readings when the Statcast system determines it has noisy data or that it missed too many samples to be confident. For example if a ball takes bounce off a bag, it will have an abrupt change in speed and direction that the system might determine is an error. In that case, the human op can step in and verify that it makes sense that the ball took a funny bounce. However, if Statcast reports an error, and there’s new discernable reason, maybe it’s best to toss the data.

After accuracy, the other crucial component is speed. MLB ideally wants to work the Statcast data into broadcasts just as fast as instant replays. As of now, the display will show when you come back after the commercial break, or a couple innings later. Before, you had to wait until the next day for a detailed breakdown of specific plays.

The biggest challenge for getting accurate data at near-instant speeds came from ground balls. In fact, Inzerillo says that reliably getting the grounder data instantaneously was the key determinant of whether or not the Statcast would go live this season. Grounders are tricky because they require both the optical and radar systems to work together.

You see, the radar is very good at reading the exact position of the ball on the field, but when the ball is on the ground, the radar can loose it. A baseball field isn’t perfectly flat and as a ball cuts through dirt and grass it rips up blades and gravel, which can throw the radar off. In this case, the optical tracking system can help verify information in these situations, jumping in to fill in the gaps when the radar looses the ball.

In the beginning, this hand off between radar and optical was manually done after the fact. For instant replays, the handoff has to be automatic — reliably and accurately automatic.

Now that it’s ready for game time, the plan is to use Statcast in-house for MLB Network broadcasts for a few months to work out the hitches, and then to roll it out to MLB’s national and regional network partners. MLB plans is to deliver Statcast data to broadcasters in a packaged for that’s ready to air, but the networks will also be free to develop their own implementations of the technology to fit with their particular broadcast styles.

Can it change the way we watch?

Building an accurate system for capturing and displaying baseball analytics is one thing, but building it into a broadcast so that its useful for viewers is entirely another.

In part this will be an evolution in design. By today’s standards, the early usage of pitch tracking technology was really clunky and ugly. Overtime can expect Statcast metrics to become shown in ways that are easier to consume. Even in the short time that Statcast has been out there, its look and feel has already evolved. In the beginning, it was full of brighter colours, which were ultimately deemed distracting to users. Today, the colours are more subdued, and shading is used to highlight just what producers want you to see.

Editorially, there are important choices that need to be made on the fly about what pieces of information are most interesting in a particular play. Even the writing and pacing of Statcast replays needs to be perfected so that fans aren’t just seeing weird numbers flash before their eyes. This Tom Verducci’s explanation of a spectacular George Springer catch shows the good and the bad of what Statcast can do.

MLB’s embeds don’t play nice in Kinja so if you wanna pause, hit space.

The first time Verducci runs through the clip with numbers, they’re flashed on the screen so fast that you can’t make any sense of them. (Lots of numbers fast is bad broadcasting 101.) It’s not until the second time he runs through numbers, highlighting Springer’s 99.1 per cent route efficiency that he really zeros in on the catch. One more wrong step on that run, and the ball goes over the right field fence before Springer can get to it. Run through one was bad, run through two was perfect.

We can also expect Statcast to get better as the technology develops. Right now, Inzerillo says that of the 200 or so data metrics his team has conceived, they can only reliably measure and calculate half of them. Of those, just 10 per cent will make it to live broadcasts at launch. Evolution in software in the short term, and the next iteration of hardware a few years down the line, will bring even more statistics into play. Whether those stats will say anything meaningful is another issue altogether.

Baseball sometimes gets a bad rap for being a lazy game that fatties can play, and Statcast has the power to showcase the real athleticism of players. It might help pull in new fans who would otherwise be distracted from Baseball’s beauty by trivialities like Twitter and the UFC. But I like to think that the real benefit will come to the people who have been fans forever in helping settle some of the most controversial questions about the game.

Consider the career of Derek Jeter, who was often criticised because his incredibly athletic plays at shortstop were often the result of poor positioning and slow reactions. Statcast would have revealed his weaknesses as a shortstoop. It might not have stripped him of his gold gloves — but maybe more rational observers would have taken a harder look at A-Rod for the position. At the end of this season. There won’t be any question about who’s the best shortstop in baseball. We’ll know.