On 12 January 1958, an important weapon of the Cold War was introduced. It wasn’t a missile or a spy satellite, but rather a colourful Sunday comic strip that showed Americans what the future was going to look like. It was called Closer Than We Think.

From 1958 until 1963, Closer Than We Think dazzled readers of the Sunday funnies — both kids and adults alike. It was launched in the wake of Sputnik, the Soviet Union satellite that terrified both the American public and the US military when it was first sent into orbit on 4 October 1957.

By January of the following year, Closer Than We Think was up and running. The first strip was called Satellite Space Station, and the subject matter was no accident. It was clearly a thinly-veiled response to the Soviet Union’s recent (and surprising) victories in the Cold War battle that would become known as the Space Race.

Detail from the 12 January 1958 edition of Closer Than We Think

Bigger and bolder than some rinky-tinky satellite, the Americans were promised that their future would include enormous space stations. The godless commies may have beaten them into space, but they were going to do it better and sleeker than anything the Soviet Union could imagine:

The far reaches of space are no longer distant. Space stations, anchored in the sky beyond the full pull of gravity, are being planned today. They will be the next, nearby step after man-made satellites have proved themselves.

Like nearly every edition of Closer Than We Think, this strip was ripped right from the headlines, even including the little “NEWS FLASH!” that was supposed to show readers that its illustrator’s drawings weren’t mere fantasy. This was the future, and it was closer than you thought possible. Don’t believe us? It’s right there in the regular part of the newspaper as well. Our illustrator, Arthur Radebaugh, is just here to show you what it will look like in full dazzling, techno-utopian colour.

The news flash in the corner of the strip, which the comic would eventually stop publishing in future editions, testified to the plausibility of the drawings:

NEW YORK, JAN. 10 — Willy Ley, famed rocket expert, described in a scientific paper how a manned space station could be set up beyond the gravity field of the earth.

Three-stage rockets, he said, would be able to leave the earth’s orbit carrying parts aboard for the station. A dozen such flights, he estimated, would provide enough components to assemble the station. The station would then be usable for further stepping stones into space.

While I’ve found no documented collusion between the creators of the comic and the US government — the strip was drawn by commercial illustrator Arthur Radebaugh, and syndicated by the Chicago Tribune — it’s clear, if only through the timing of its release, that this peek into the future was a direct response to Sputnik. And it served the stated goal of American military and government leaders to get kids interested in science and technology.

The other comic strip launched in the direct wake of Sputnik was more explicit in its mission to battle the Soviets on the technological stage. Our New Age, written by the South African-American academic Athelstan Spilhaus, wasn’t just about the future. But it often featured futuristic elements to tell the story of how science and technology were important.

“Rather than fight my own kids reading the funnies, which is a stupid thing to do, I decided to put something good into the comics, something that was more fun and that might give a little subliminal education,” Spilhaus would tell a researcher years later.

While Our New Age would run for many years longer than Closer Than We Think, it was Arthur Radebaugh’s illustrations of twirling space stations, super-sized vegetables, and high-tech living rooms, that would stick in childrens’ minds years for the decades to come.

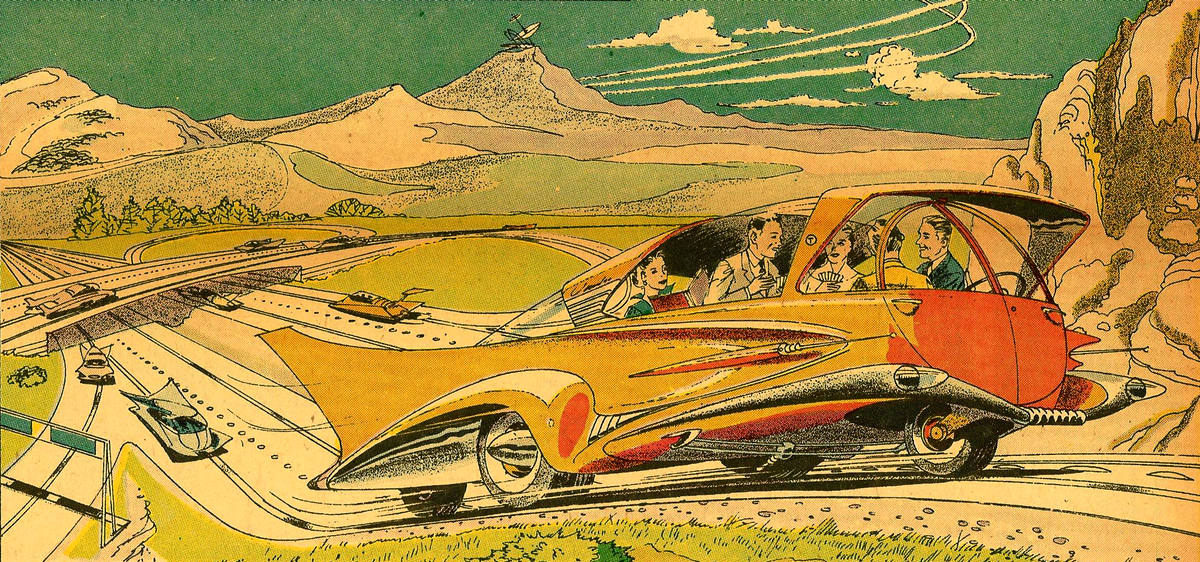

Driverless car of the future, as depicted in the 22 February 1959 edition of Closer Than We Think

But perhaps Closer Than We Think’s greatest legacy wasn’t the direct impression it had on kids. No, Closer Than We Think may have been most important because it was clearly the continual inspiration for a little show that launched in September of 1962: The Jetsons.

Time and again, you can see the themes and technologies presented in Closer Than We Think pop up in The Jetsons. And despite the fact that the cartoon TV show is now over a half century old, amazingly it’s still a common way to talk about the future of the 21st century.

So the next time you’re pining for your flying car, your jetpack, or your vacation on the moon, you can probably both thank and curse Closer Than We Think. Because the strip didn’t invent these concepts. But it helped firmly implant those futuristic ideas into generations of kids who grew up on the Sunday funnies and Saturday morning cartoons.

Sadly, many of them weren’t so closer after all.