This week, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg appeared to publicly denounce the political positions of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign during the keynote speech of the company’s annual F8 developer conference.

“I hear fearful voices calling for building walls and distancing people they label as ‘others’,” Zuckerberg said, never referring to Trump by name. “I hear them calling for blocking free expression, for slowing immigration, for reducing trade, and in some cases, even for cutting access to the internet.”

For a developer’s conference, the comments were unprecedented — a signal that the 31-year-old billionaire is quite willing to publicly mix politics and business. Zuckerberg has donated to campaigns in the past, but has been vague about which candidates he and his company’s political action committee support.

Inside Facebook, the political discussion has been more explicit. Last month, some Facebook employees used a company poll to ask Zuckerberg whether the company should try “to help prevent President Trump in 2017.”

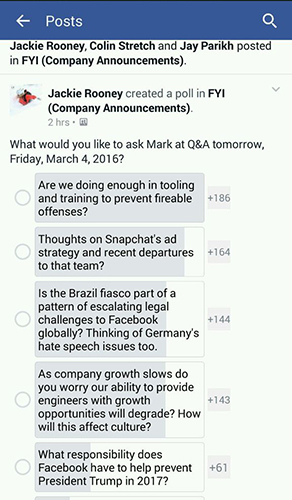

image: Gizmodo

Every week, Facebook employees vote in an internal poll on what they want to ask Zuckerberg in an upcoming Q&A session. A question from the March 4 poll was: “What responsibility does Facebook have to help prevent President Trump in 2017?”

A screenshot of the poll, given to Gizmodo, shows the question as the fifth most popular.

It’s not particularly surprising the question was asked, or that some Facebook employees are anti-Trump. The question and Zuckerberg’s statements earlier this week align with the consensus politics of Silicon Valley: pro-immigration, pro-trade, pro-expansion of the internet.

But what’s exceedingly important about this question being raised — and Zuckerberg’s answer, if there is one — is how Facebook now treats the powerful place it holds in the world. It’s unprecedented. More than 1.04 billion people use Facebook. It’s where we get our news, share our political views and interact with politicians. It’s also where those politicians are spending a greater share of their budgets.

And Facebook has no legal responsibility to give an unfiltered view of what’s happening on their network.

“Facebook can promote or block any material that it wants,” UCLA law professor Eugene Volokh told Gizmodo. “Facebook has the same First Amendment right as the New York Times. They can completely block Trump if they want. They block him or promote him.” But the New York Times isn’t hosting pages like Donald Trump for President or Donald Trump for President 2016, the way Facebook is.

Most people don’t see Facebook as a media company — an outlet designed to inform us. It doesn’t look like a newspaper, magazine or news website. But if Facebook decides to tamper with its algorithm — altering what we see — it’s akin to an editor deciding what to run big with on the front page, or what to take a stand on. The difference is that readers of traditional media (including the web) can educate themselves about a media company’s political leanings. Media outlets often publish op-eds and editorials, and have a history of how they treat particular stories. Not to mention that Facebook has the potential to reach vastly, vastly more readers than any given publication.

With Facebook, we don’t know what we’re not seeing. We don’t know what the bias is or how that might be affecting how we see the world.

Facebook has toyed with skewing news in the past. During the 2008 presidential election, Facebook secretly tampered with 1.9 million user’s news feeds. An academic paper was published about the secret experiment, claiming that Facebook increased voter turnout by more than 340,000 people. In 2010, the company tampered with news feeds again. It conducted at 61-million-person experiment to see how Facebook could impact the real-world voting behaviour of millions of people. In 2012, Facebook deliberately experimented on its users’ emotions. The company, again, secretly tampered with the news feeds of 700,000 people and concluded that Facebook can basically make you feel whatever it wants you to.

If Facebook decided to, it could gradually remove any pro-Trump stories or media off its site — devastating for a campaign that runs on memes and publicity. Facebook wouldn’t have to disclose it was doing this, and would be protected by the First Amendment.

But would it be ethical?

“I’m inclined to say Facebook has the same responsibility of any legacy media company,” said Robert Drechsel, a professor of journalism ethics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He thinks Facebook should provide coverage that is thorough, fair, accurate, complete and contextual. “There is no legal issue.”

The only way that Facebook could legally overstep, experts say, is by colluding with a given candidate. “If Facebook was actively coordinating with the Sanders or Clinton campaign, and suppressing Donald Trump news, it would turn an independent expenditure (protected by the First Amendment) into a campaign contribution because it would be coordinated — and that could be restricted,” Volokh said.

“But if they’re just saying, ‘We don’t want Trump material on our site,’ they have every right to do that. It’s protected by the First Amendment.”

We’ve reached out to Facebook for comment but had not heard back at time of writing.

Image: AP