On 11 December 1972, Apollo 17 touched down on the Moon. This was not only our final Moon landing, but the last time we left low Earth orbit. With the successful launch of the Orion capsule, NASA is finally poised to go further again. So it’s important to remember how we got to the Moon — and why we stopped going.

Crewed by Commander Eugene A. Cernan, Command Module Pilot Ronald E. Evans and Lunar Module Pilot Harrison P. Schmitt, the Apollo 17 mission was the first to include a scientist. The primary scientific objectives included “geological surveying and sampling of materials and surface features in a preselected area of the Taurus-Littrow region; deploying and activating surface experiments; and conducting in-flight experiments and photographic tasks during lunar orbit and transearth coast.”

Harrison ‘Jack’ Schmitt had earned his PhD in Geology from Harvard University in 1964, and had worked for the United States Geological Survey and at Harvard University before going through Astronaut training in 1965. Apollo 17 was his first mission into space, and would be the first astronaut-scientist to step on the surface of the Moon. Accompanying him was Eugene ‘Gene’ Cernan, a veteran astronaut who had first flown into space with the Gemini IX-A mission in 1966 and later served as the Lunar Module Pilot for the Apollo 10 mission in May of 1969, where he came within 145km of the Lunar surface.

04 14 21 43: Schmitt: Schmitt: Stand by. 25 feet, down at 2. Fuel’s good. 20 feet. Going down at 2. 10 feet. 10 feet –

04 14 21 58: Schmitt: CONTACT.

04 14 22 03: Schmitt: *** op, push. Engine stop; ENGINE ARM; PROCEED; COMMAND override, OFF; MODE CONTROL, ATT HOLD; PGNS, AUTO.

Cernan landed the Challenger Lunar Module in the Taurus-Littrow lunar valley, just to the southeast of Mare Serenitatis, a region of geological significance on the Moon. The mission’s planners hoped that the region would provide a wealth of information about the history of the Moon’s surface. Upon landing, the pair began their own observations of the lunar surface:

04 14 37 05: Cernan: “You know, I noticed there’s even a lot of difference in earthshine and – and in the double umbra. You get in earthshine on the thing, and it’s – it’s hard to see the stars even if you don’t have the Earth in there.”

04 14 23 28: Cernan: “Oh, man. Look at that rock out there.”

Schmitt: “Absolutely incredible. Absolutely incredible.”

After several hours of preparation, Cernan stepped onto the Lunar surface:

04 18 31 0: “I’m on the footpad. And, Houston, as I step off at the surface at Taurus-Littrow, I’d like to dedicate the first step of Apollo 17 to all those who made it possible. Jack, I’m out here. Oh, my golly. Unbelievable. Unbelievable, but is it bright in the Sun. OK. We landed in a very shallow depression. That’s why we’ve got a slight pitch-up angle. Very shallow, dinner-plate-like.”

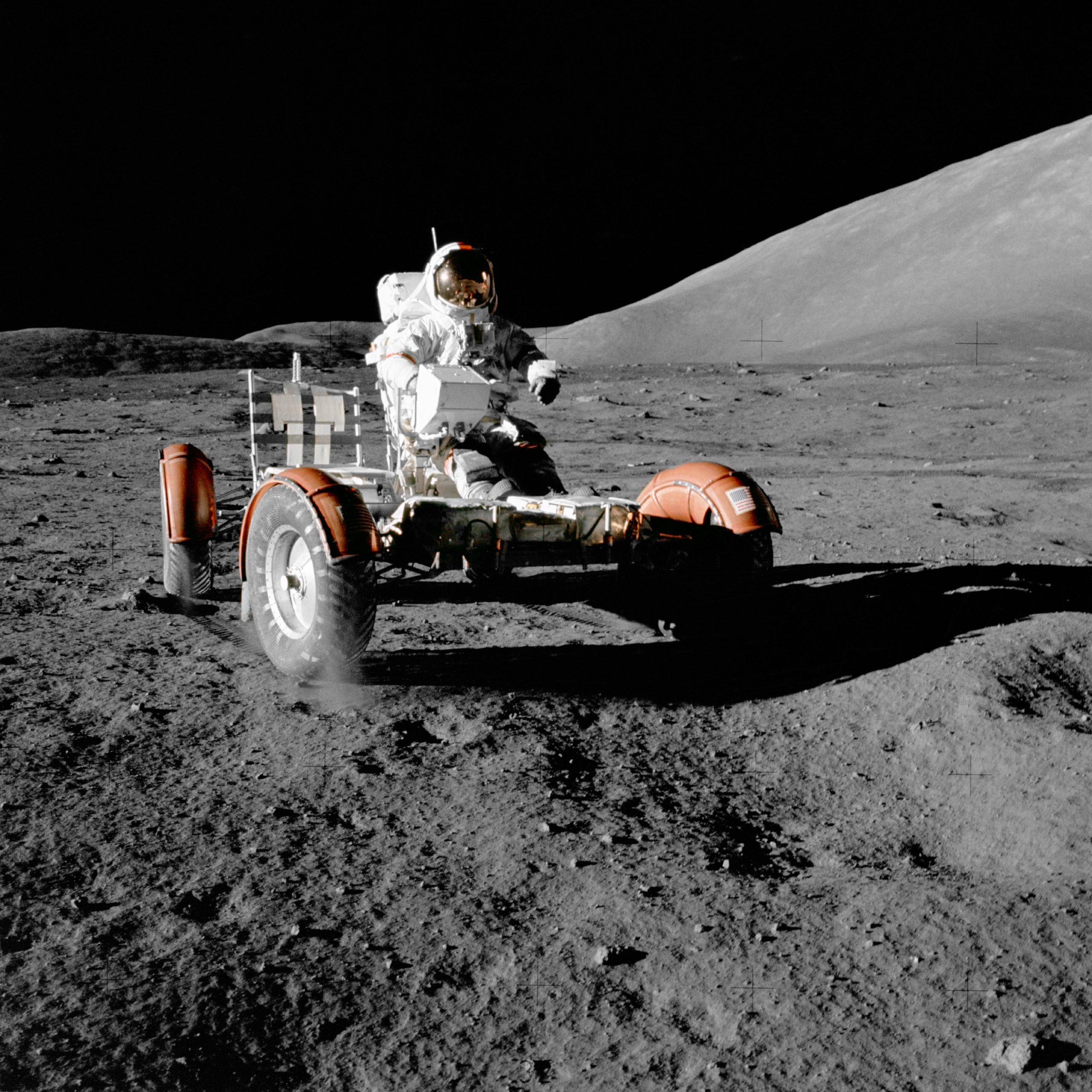

The two astronauts unloaded a lunar rover, and began to deploy scientific instruments around their landing site: an experiments package and explosives (to complete seismic experiments begun with other Apollo missions in other locations on the Moon). Their first exclusion in the rover yielded numerous samples of lunar rock. Over the next couple of days, the astronauts completed two additional Moon walks, where they continued to drive across the lunar surface and collect samples.

Schmitt later described the landing site to NASA Oral historian Carol Butler: “It was the most highly varied site of any of the Apollo sites. It was specifically picked to be that. We had three-dimensions to look at with the mountains, to sample. You had the Mare basalts in the floor and the highlands in the mountain walls. We also had this apparent young volcanic material that had been seen on the photographs and wasn’t immediate obvious, but ultimately we found in the form of the orange soil at Shorty crater.”

Why we went to space

The scientific endeavours of Apollo 17 were the culmination of a massive program that had begun in 1963 following the successes of the Mercury Program. In the aftermath of the Second World War, the United States and Soviet Union became embroiled in a competitive arms race that saw significant military gains on both sides, eventually culminating in the development of rockets capable of striking enemy territory across the world. The next step for arms superiority jumped from the atmosphere to Low Earth Orbit to the Moon, the ultimate high ground. As this happened, each country capitalised on the advances in rocket technology to experiment with human spaceflight missions. The Soviet Union succeeded in putting Yuri Gagarin into space in 1961, just a couple of years after launching the first satellite into orbit.

Closely followed by the United States, space became an incredibly public demonstration of military and technological might. The development of space travel didn’t occur in a political vacuum: the drive for the United States to develop rockets and vehicles which could travel higher and faster than their Soviet counterparts happened alongside increasing US/USSR tensions, especially as geopolitical crises such the Cuban Missile Crisis and the US deployment of missiles to Turkey demonstrated how ready each country was to annihilating the other.

Image via Universe Today

As the space program took off, it was supported by other research and scientific efforts from the broader military industrial complex which President Dwight Eisenhower had worried about just a handful of years earlier. (Eisenhower had not been a major supporter of the development of space travel which began under his watch, and had attempted to downplay the significance of Sputnik.) The red hot environment of the Cold War allowed for significant political capital and governmental spending which supported a first-strike infrastructure, and in part, trickled over to the scientific and aeronautical fields, which maintained a peaceful and optimistic message.

By 1966, the space race peaked: NASA received its highest budget ever, at just under 4.5% of the total US federal budget, at $US5 ($7).933 billion dollars (around $US43 ($56) billion today.) The United States had made clear gains in space by this point: Project Gemini had completed its final mission, and with efforts towards the next phase under Apollo were well under way. By this point, the social and political infrastructure and support for space had begun to wane, and would ultimately fall away after Apollo 11 successfully landed on the Moon’s surface in July of 1969. After this point, NASA continued with planned missions, and eventually landed five additional Apollo missions on the Moon. (Another, Apollo 13, was unable to land after mechanical problems).

Changing priorities

Just a year after Apollo 11 landed, NASA began to reprioritize: plans for a space station were revived, and in 1970, they announced that Apollo 20 would be cancelled in favour of the creation of a new venture: Skylab. On September 2nd, 1970, the agency announced the final three Apollo missions: Apollo 15, 16 and 17. The agency was forced to contend with political pressure as well: In 1971, the White House intended to completely cancel the Apollo program after Apollo 15, but ultimately, the two remaining Apollo missions were kept in place. Harrison Schmitt, who had been training for Apollo 18, was bumped up to Apollo 17 after NASA faced pressure from scientists to send one of their own to the Moon.

On 14 December 1972, Cernan became the last human to step on the Moon’s surface:

07 00 00 47: “Bob, this is Gene, and I’m on the surface and as I take man’s last steps from the surface, back home, for some time to come, but we believe not too long into the future. I’d like to Just list what I believe history will record that America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the Moon at Taurus Littrow, we leave as we come and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17.”

In the forty-two years since those words were spoken, nobody has stepped on the Moon. The levels of federal spending which NASA had received before 1966 had become untenable to a public which had become financially wary, particularly as they experienced a major oil crisis in 1973, which shifted the nation’s priorities. Spending in space was something that could be done, but with far more fiscal constraints than ever before, limiting NASA to research and scientific missions in the coming years. Such programs included the development of the Skylab program in 1973, and the Space Shuttle program, as well as a number of robotic probes and satellites.

This shift in priorities deeply impacted the willpower of policymakers to implement new exploratory missions to the Moon and beyond. Optimistic dreams of reaching Mars had long since perished, and as NASA focused on the Space Shuttle, the physical infrastructure which supported lunar missions vanished: No longer were Saturn V rockets manufactured, and unused rockets were turned into museum displays. The entire technical and manufacturing apparatus, which has supported both military and civilian operations, had likewise begun to wind down. The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) and its successors began to freeze the numbers of missiles which could be deployed by both the United States and Soviet Union in 1972, and each country largely began to step down their operations. The urgency which fuelled the Cold War arms race had begun to cool, and along with it, the support for much of the efforts required to bring people into space and to the Moon.

Since that time, US Presidents have spoken of their desire to return to the Moon, but often in terms of decades, rather than in single digits. It’s easy to see why: up until recently, US spaceflight operations were focused entirely on Low Earth Orbit activities, as well as admirable cooperative international programs such as the International Space Station, and major scientific instruments such as Mars Pathfinder, Opportunity/Spirit and Curiosity. Other major concerns have redirected US attentions from spaceflight: the United States’ War on Terror, which is expected to cost US taxpayers over $US5 ($7) trillion dollars in the long run.

The launch of Orion atop a Delta IV Heavy rocket was exciting to watch, as well as newer players in the space launch field, SpaceX and Orbital Sciences Corporation, which suggesting that a new generation of infrastructure is being constructed. The reasons for visiting the Moon and potentially, other planets and bodies in our solar system, are numerous: they could be the greatest scientific endeavours of our existence, allowing us to further understand the creation of our planet and solar system and the greater world around us. More importantly though, such missions contribute to the character of the nation, demonstrating the importance of science and technology to our civilisation, which will ultimately help us process and address the issues of greatest concern: the health of our planet. Hopefully, Cernan’s words and hope that our absence from the Moon will be short-lived, and that we will once again explore new worlds in our lifetimes.