Scientists have sustained human embryos in a petri dish for 13 days, shattering the previous record of nine days. The breakthrough will allow researchers to study early foetal development in unprecedented detail, and brings us one step closer to viable “artificial wombs”. But it’s adding fuel to an already heated ethical debate.

Two separate papers published this week, one in Nature and one in Nature Cell Biology, have reported culturing human embryos for nearly two weeks, going well beyond previous efforts. There’s no reason to believe that the embryos couldn’t have survived beyond the two-week mark, but the experiment had to be halted to adhere to the internationally agreed 14-day limit on human embryo research.

Prior to this study, scientists had only been able to study this mysterious stage of human development until the seventh day. Then they had to implant the embryos into the mother’s uterus so it could survive and develop normally. Using a culture method developed at the University of Cambridge, the researchers were able to extend this to 13 days.

“Implantation is a milestone in human development as it is from this stage onwards that the embryo really begins to take shape and the overall body plan are decided,” Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz — who led both studies — said in a statement. “But until now, it has been impossible to study this in human embryos. This new technique provides us with a unique opportunity to get a deeper understanding of our own development during these crucial stages and help us understand what happens, for example, during miscarriage.”

What’s more, the technique could allow scientists to better understand the consequences of foetal alcohol syndrome, the causes of conditions like autism and why certain chemicals affect embryonic development. It could also be used to study the neurological effects of transmissible diseases such as the Zika virus.

There are two important takeaways from this research. “First, advances in technology have allowed the growth of embryos in a lab past the time which many scientists thought possible,” said University of California cellular biologist Peter Donovan, who wasn’t involved in the study. Second, critical aspects of early fetal development aren’t dependant on it being attached to the mother. “So now science has a method to study a key period of human development that up until now has largely remained a black box,” added Donovan.

This new study is also rekindling the debate about the need for such experiments, and whether the 14-day rule should be revised and expanded. It’s challenging conventional notions of embryonic and foetal viability outside the womb.

At the 14-day mark, the embryo forms a structure called the “primitive streak” that signifies the time when it has developed a discernible head and tail end. Before this stage, the embryo is basically just a clump of cells that has the potential to split into multiple individuals. Thus, some say it’s the critical stage at which an embryo becomes a discrete individual.

Others argue that this “individuality”, or personhood, doesn’t arise until much later, such as the point of viability outside the womb (usually around 23 weeks). So the ability to sustain an embryo outside the womb at this early stage adds a new wrinkle to this often controversial and heated dialogue.

Stanford School of Medicine legal expert Frank Greely isn’t convinced about the scientific efficacy of this research or the need to go beyond the 14-day limit.

“[If] we do not use a 14 day rule, what limit will we use? Twelve weeks or so as in many European abortion laws? Viability as in US abortion law?” he asked. “Human development is a seamless process, but ultimately lines need to be drawn even when — especially when — they do not naturally exist. I do not see a politically or, for most people, morally acceptable line after 14 days. Given the questionable scientific value of the research, no case has been made for even revisiting the line, let alone changing it.”

Greely is off the mark by claiming that this line of research has “questionable scientific value”, but he’s right in saying that rules should exist for this type of research. Rules, though restrictive, ensure safety and efficacy. Once scientists get a handle on the new bounds created by their research, restrictions can then be modified and extended further to allow science to continue.

It’s a conversation that can’t simply be swept under the rug. We’re inching closer and closer to the day when it will finally become possible to grow a baby entirely outside the human body.

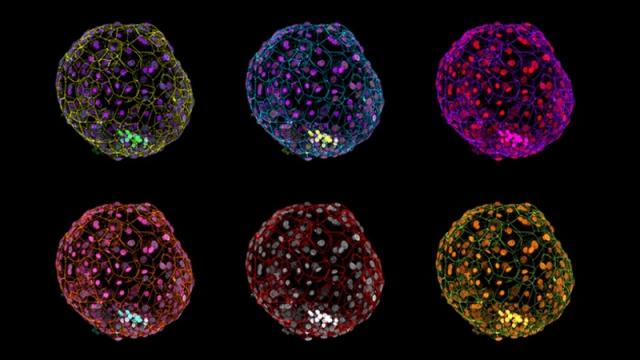

Image: Alessia Deglincerti, Gist Croft, and Ali H. Brivanlou