Traditional farming is taking a huge toll on the environment — a problem that’s set to worsen due to our ever-growing global population. Yet there are some high-tech solutions. Here’s what you need to know about the burgeoning practice of controlled-environment agriculture and how it’s set to change everything from the foods we eat to the communities we live in.

As a practice, traditional farming is not going to disappear any time soon. It will be quite some time — if ever — before other methods completely supplant it. But it’s crucial that alternatives be devised to alleviate the pressure imposed by conventional farming methods.

An Unsustainable Practice

Negative environmental effects of traditional farming include the steady decline of soil productivity, over-consumption of water (including water pollution via sediments, salts, pesticides, manures, and fertilisers), the rise of pesticide-resistant insects, dramatic loss of wetlands and wildlife habitat, reduced genetic diversity in most crops, destruction of tropical forests and other native vegetation, and elevated levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. And as urban sprawl continues unabated, vast swaths of productive farmland are being eliminated. Estimates place the amount of farmland lost to development since 1970 at a whopping 30 million acres.

Pesticide sprayer (Credit: PI77/CC BY-SA 3.0)

There are economic and social concerns as well. In addition to relying on huge federal expenditures, Big Agriculture has resulted in widening disparity among farmer incomes, concentrating agribusiness into fewer hands, and limited market competition. What’s more, farmers have very little control over prices, while progressively receiving smaller and smaller portions of consumer dollars. From 1987 to 1997, for example, more than 155,000 farms were lost in North America. As noted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, this “contributes to the disintegration of rural communities and localised marketing systems.”

Controlled-environment Agriculture

As a solution, an increasing number of horticulturalists and entrepreneurs are turning to controlled-environment agriculture (CEA), and the related practice of vertical farming. While not a total panacea, these high-tech farms are doing much to address many of the problems associated with conventional farming practices.

One company that’s leveraging the power of CEA is IGES Canada Ltd. Headed by President and Executive Director Michel Alarcon, IGES is working to own and operate a number of CEA facilities in both populated and remote communities. The company’s overriding mandate is to rebuild resilient communities and dramatically reduce CO2 emissions.

As Alarcon explained to io9, environmentally-controlled farms like the one implemented by IGES have a number of inherent advantages. Compared to conventional farms (and depending on the exact configuration and technologies used), they’re around 100 times more efficient in terms of their usage of space, 70-90% less reliant on water, with a lower CO2 footprint. Foods are grown without the use of pesticides, they’re nutrient-rich, and free from chemical contaminants. And because they can be built virtually anywhere, CEAs can serve communities where certain foods aren’t normally grown.

Alarcon plans to introduce his company’s technology to northern regions of Canada, where they would serve aboriginal populations. Conceivably, such facilities could be installed in any number of extreme environments, including the desert or in regions stricken by drought.

These facilities, which are used by IGES to produce broad leaf products like micro-greens, herbs, and soft fruit, can produce 912 metric tons per year in a 10,000 square meter space. And that’s via horizontal farming, IGES’s preferred method of CEA. With increased roll-out of these facilities, the company can supplant foreign food imports during winter months.

“The savings from a reduction in transportation costs will enable the price of our food to be less than organic food prices,” says Alceron.

(Credit: Goldlocki/Hochgeladen von Rasbak/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Operations like the ones visualized by IGES Canada likely will have a profound impact on local communities. CEAs will make certain foods available year-round, providing a variety of healthy food sources, while creating local employment and promoting cultural preservation.

IGES Canada will soon be initiating a crowd financing campaign, while expanding its equity financing partner base.

The VertiCrop System (Credit: Valcentu/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Startup costs for ventures like these can be intense. A few years ago in Vancouver, a company sought to install a massive greenhouse for vertical lettuce production on top of a city-owned parking structure, but failed. Some of it had to do with investors and contracts with the city, but it was also hampered by high startup costs relative to the resulting crop yields. As Foodshare Senior Coordinator Katie German explained to io9, many of the farms are also set up to grow food for restaurants — growing for high price points — and are not necessarily concerned about making food more accessible (which the high startup costs requires). Currently, the Vancouver company is trying to sell their failed $US1.5 ($2) million greenhouse on craigslist.

AeroFarms is currently building the world’s largest vertical farm in Newark, NJ. (Credit: AeroFarms)

At the same time, there have been a number of successful implementations, including Green Sense Farms in Portage, Indiana. They’re currently leasing a 30,000-square-foot warehouse in an industrial park which can serve a five-state Midwestern region. According to its CEO, Robert Colangelo, “By growing crops vertically, we are able to achieve a higher yield, with a smaller footprint.”

Other successful examples include plant factories set up by the Mirai Group, and the Zero Carbon Food’s operation in which a WWII bomb shelter was converted into a high-tech underground farm.

“The whole system runs automatically, with an environmental computer controlling the lighting, temperature, nutrients and air flow,” noted Steven Dring, co-founder of the company, in a Bloomberg article.

Tools of the Trade

Environmentally-controlled farming is more than just a glorified form of hydroponics. These facilities employ a number of sophisticated techniques and technologies to produce nutritious and tasty foods at reasonably high yields.

Polarised Water

One critical component of the IGES model is the use of polarised water, which enables water to hold on to a greater amount of nutrients.

“The injection of energy in water modifies the bond angle of hydrogen and oxygen atoms and makes the molecular structure more attractive to nutrients, and therefore carry a higher amount of these nutrient to root and plant leaf surface and increasing growth rate,” explained Alarcon.

This process also increases redox effect (oxidation) and elimination of bacterial and microbial pathogens.

CO2 Injection

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is an essential component of photosynthesis, a process also called carbon assimilation.

Photosynthesis is a chemical process that uses light energy to convert CO2 and water into sugars in green plants. These sugars are then used for growth within the plant, through respiration. The difference between the rate of photosynthesis and the rate of respiration is the basis for dry-matter accumulation, i.e. growth, in the plant.

“In greenhouse production the aim of all growers is to increase dry-matter content and economically optimise crop yield,” Alarcon told io9. “CO2 increases productivity through improved plant growth and vigour.”

For the majority of greenhouse crops, net photosynthesis increases as CO2 levels increase from 340 — 1,000 ppm (parts per million). According to Alarcon, most crops show that for any given level of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), increasing the CO2 level to 1,000 ppm will increase the photosynthesis by about 50% over ambient CO2 levels.

Ambient CO2 level in outside air is about 340 ppm by volume. All plants grow well at this level, but as CO2 levels are raised by 1,000 ppm, photosynthesis increases proportionately, resulting in more sugars and carbohydrates available for plant growth.

And CEAs provide an excellent venue for our excess CO2.

Microalgae Photobireactor

These bioreactors employ a light source and photosynthesis to cultivate phototrophic microorganisms (those that use energy from light to fuel metabolism), including plants, mosses, microalgae, cyanobacteria, and purple bacteria.

(Credit IGV Biotech/CC BY-SA 3.0)

It typically allows for much higher growth rates and purity levels than in natural habitats. Photobioreactors transform CO2 into highly nutritious plant food which is readily absorbed by plants.

Climate Control

The internal environment of CEAs must be carefully maintained, including steady temperature, humidity, and isolation from external air. Climate control minimizes plant environmental stress and exposure to harmful pests.

Lighting

Similarly, optimal multi-spectrum lighting and light exposure can be applied year-round, regardless of season and natural light availability. Recently, LED grow lights have evolved to offer multi spectrum lighting range, thus enabling a broader range of plant varieties to thrive in this environment.

Scalability

These facilities are also highly scalable. IGES Canada’s operations are scalable from a 1/4 acre (250m2) operation to multiples of 3 acres (10,000m2) facilities.

Tempering Expectations

According to Timothy Hughes, an organic horticulture specialist working in Toronto, the potential social benefits to enviro-controlled farming are enormous.

“Local, dense food production spaces would provide permanent green-sector employment, as well as an excellent educational model — providing a wider knowledge base for students and employees alike,” Hughes told io9. “From one farm, you could produce vegetables, fruit, honey, fish, and textiles, for example. And by expanding the variety of crops produced, you’re ensuring overall success through diversity.”

At the same time, however, Hughes says that environmentally-controlled farming may be technologically flashy, but it’s not as efficient as it’s being touted. He points to high building maintenance and energy costs, along with ongoing technological investments.

“In terms of plant life, these systems are often reliant on technology, such as powering the hydroponics,” he says. “This could be a bad thing for struggling or remote communities when reliant on these types of technology — we’re only beginning to understand these kinds of vertical farms because they haven’t been built beyond traditional greenhouses.”

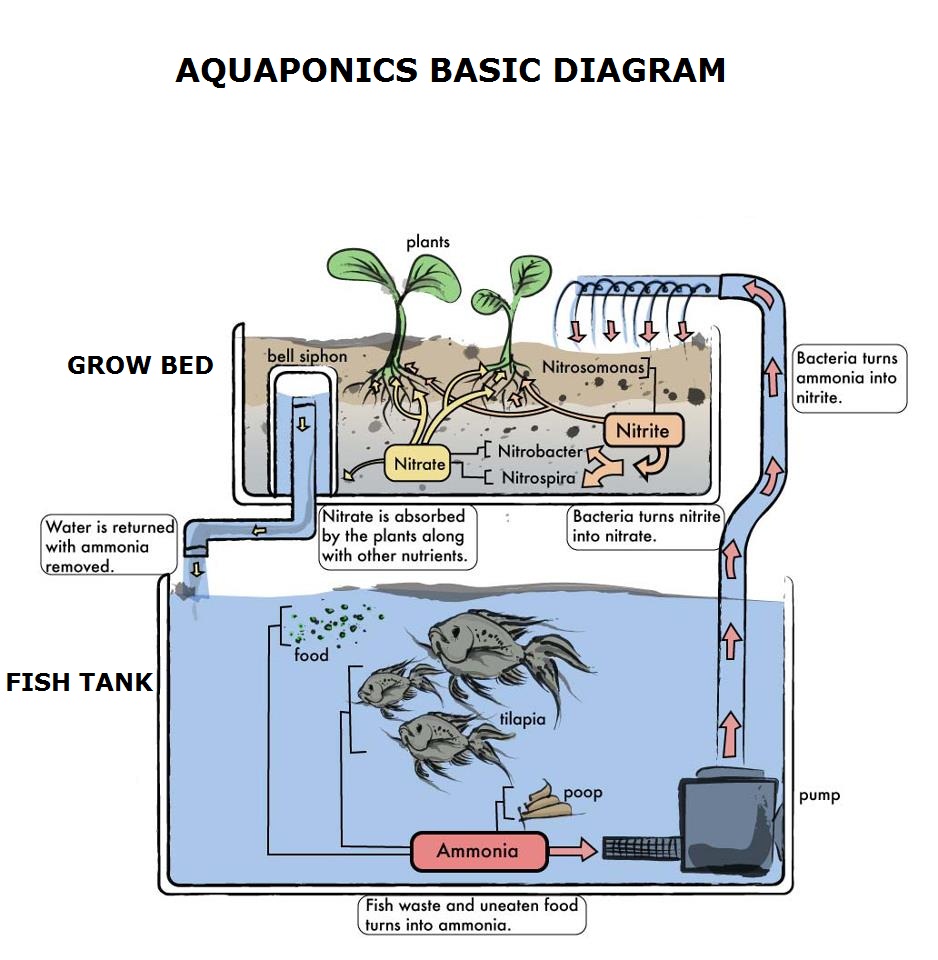

Hughes would rather see the money spent on labour and horticultural infrastructure innovations than on enormously expensive megastructures. He points to permaculture as a possible alternative — aquaponics in particular. Aquaponics is a system of symbiotically growing hydroponic vegetables and fish. This delivers two high-value crops while sharing resources, reducing or totally eliminating waste, and increasing energy efficiency during production.

(Credit: Johnson State College)

“I believe this maintains a scientific approach, through taking a lesson from more traditional farming — which we know works — and augmenting it,” says Hughes. “Current greenhouses are already quite technologically advanced and have a huge amount of research put into them in terms of light technology and environmental controls. Why not build upon what we already have?”

Currently, aquaponics is in use, but not widely. Hughes envisions growing this to a larger scale, in more urban spaces, with a greater and denser mass of growing space.

“Vertical farming systems have a lot to offer, but you can further increase productivity and value through increasing biodiversity, and by doing so furthering the benefit to local communities,” he says. “Biodiversity is important to the survival of all organisms, but is especially beneficial when replicating or improving a healthy growing environment. By using an Integrated Pest Management system to monitor crops and greenhouse systems, other organisms (such as pollinating and beneficial insects) can thrive in a constructed ecosystem.”

And then there’s the issue of soil — or lack thereof. According to Katie German, there has been some pushback from organic farmers about not having any soil, and farming is fundamentally about soil and biology.

“If you don’t have soil fertility you might be going with synthetic fertility — which has a whole myriad of implications in regards to how it was produced and where that might negate other ways of reducing pollution,” says German. She points to the work of Elliot Coleman, a veteran organic farmer who says you can’t have organic food without soil.

Lastly, German says many of us are guilty of failing to acknowledge the ongoing importance of farms.

“If we talk about urban food production innovation, but lose the conversation and struggle for farmland preservation, then we are doomed,” she told io9. “I think sometimes these high-tech environmentally controlled farms are sexy, but we have to make soil sexy. The UN released this report that said if we really want to feed the whole world then we need to shift to small scale organic agriculture. Which isn’t sexy like growing butter lettuce in a shipping container outside of your farm-to-table restaurant.”

In response to these concerns, IGES Canada says that their offering, along with those of other CEA ventures, are a complement to traditional agriculture.

“The goal isn’t to grow every crop using this method, just generally the leafy greens and soft fruits,” explained Patrick Hanna, IGES’s Director of Marketing and Promotional Campaigns. “Cities still require farmers to provide wheat, soy, potatoes, peppers, and so on. I am of the opinion our system compliments them.”

Hanna points out that some 80% of the world’s arable land is currently being used by farming. And with the expected population growth, we need to find solutions to this looming issue.

“On the topic of small scale organic production, I actually agree that is the future and we intend to use this system to augment that for small scale communities, in partnership with local farmers,” adds Hanna. “We see the problems created by ‘Big Ag’ and have developed a system to mitigate a large segment of the problems created by that unsustainable, large scale, decentralized model.”

Sources: leafcertified.org | USDA